|

|

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

| Year : 2016 | Volume

: 4

| Issue : 2 | Page : 25-31 |

|

Quality of life in subjects with shortened dental arch rehabilitated with removable metal-based partial dentures

Julie O Omo1, Mathew A Sede1, Temitope Ayodeji Esan2

1 Department of Restorative Dentistry, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria

2 Department of Restorative Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

| Date of Web Publication | 14-Sep-2016 |

Correspondence Address:

Dr. Temitope Ayodeji Esan

Department of Restorative Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife

Nigeria

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None  | Check |

DOI: 10.4103/2347-4610.190606

Context: Previous studies showed that treatment of shortened dental arch (SDA) subjects with metal-based removable partial denture (RPD) did not significantly improve their quality of life (QoL). Objective: To assess the effect of metal-based RPDs on the QoL of patients in Nigeria with SDA using the oral health impact profile 49 (OHIP-49). Materials and Methods: The study was an interventional study consisting of 36 consecutive patients attending the Prosthetic Dental Clinic of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria and met the inclusion criteria. The patients completed the OHIP-49 questionnaire before treatment and 3 months after insertion of the metal-based denture. All the relevant information gathered from the subjects was recorded in the data collection sheet. Data analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 17.0). Statistical significance was inferred at P < 0.05. Results: A total of 36 patients consisting of 24 (66.7%) females and 12 (33.3%) males participated in the study. The age range of the subjects was 34-64 years with a mean age of 52.2 ± 8.2 years. There was a significant improvement in the mean scores of all the domains of OHIP-49 and the total mean score of OHIP-49 3 months after treatment. Irrespective of age, gender, saddle type, and saddle location, there was a significant improvement in the QoL of the patients 3 months after treatment with metal-based RPD. Conclusion: Within the limitations of this study, there was an improvement in the QoL of subjects with SDA after treatment with RPDs. Keywords: Oral health-related quality of life, removable partial denture, shortened dental arch

How to cite this article:

Omo JO, Sede MA, Esan TA. Quality of life in subjects with shortened dental arch rehabilitated with removable metal-based partial dentures. Eur J Prosthodont 2016;4:25-31 |

How to cite this URL:

Omo JO, Sede MA, Esan TA. Quality of life in subjects with shortened dental arch rehabilitated with removable metal-based partial dentures. Eur J Prosthodont [serial online] 2016 [cited 2018 Jun 29];4:25-31. Available from: http://www.eurjprosthodont.org/text.asp?2016/4/2/25/190606 |

| Introduction | |  |

Tooth loss of one or more natural teeth often results in disability that affects essential daily living activities such as speaking, eating, self-esteem, and nutrition. [1] A systematic review showed a fairly strong association between tooth loss and impairment of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) and its severity is dependent on the location and distribution of the loss. [2] Furthermore, treatment of partially and completely edentulous arch showed a positive effect on QoL. [3] Traditionally, dentistry emphasized the necessity of a total repair of the dentition to maintain complete dental arches. [4] In doing so, several therapeutic concepts for the replacement of teeth are used such as removable partial dentures (RPDs), fixed partial dentures, and implant treatment. [5],[6] The advantages of receiving RPD treatment include the restoration of appearance, improved masticatory function, prevention of undesirable morphological effects of tooth loss including alveolar bone resorption, alteration of the occlusal plane, and movement of the remaining teeth. [5] However, significant adverse complications have been associated with RPD treatment such as plaque accumulations, increased incidence of caries and periodontal breakdown, occlusal loading of soft tissues, gingival discomfort, and direct trauma. [7]

The traditional viewpoint has been challenged by some studies. [8],[9] Lately, some authors have suggested a "problem-solving approach," in the management of free-end saddle in which the patient's dental problems are inventorized and treatment directed toward solving them. [10],[11] This is the concept of the shortened dental arch (SDA).

SDA refers to a functional, esthetic, and natural dentition of not more than twenty teeth with an intact anterior region but a reduced number of occluding pairs of posterior teeth. [12] The "SDA concept" is a treatment strategy aimed at providing satisfactory oral function when there are limitations for optimal dental care. The criteria for the application of SDA concept include dental problems confined to posterior teeth, good prognosis for 10 pairs of anterior and premolar teeth, limited possibilities for extensive restorative care, absence of parafunction or mandibular dysfunction, and when the biologic price of fitting a denture will be high. [11]

Strong reservations have been expressed in the past about adopting this pragmatic SDA approach [13] while a vast majority of dentists agree that the approach is acceptable and appropriate in clinical practice; they show hesitation toward its implementation. [4]

While many studies have shown that SDA is a pragmatic approach at solving the problems of free-end saddle dentures with its frequent technical complications from the dentists' point of view, only few looked at this concept from the patients' perspective. It should be noted that the main reason for replacing molars is to improve function. From functional point of view, the type of diet would be a strong factor in determining the perception of such patient about the need for replacement or otherwise. No study has shown the influence of diet on daily life activities of SDA patients.

One of the ways to measure the impact of SDA on daily life activities is to use the OHRQoL. OHRQoL characterizes a person's perception of how oral health influences an individual's life quality and overall well-being. [14] The oral health impact profile 49 (OHIP-49) is a theoretical model developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) [15] and adapted for oral health by locker. [16] It hierarchically links the consequences of oral disease; from a biological level (impairment) to a behavioral level (functional limitation, discomfort, and disability) and finally to the social level (handicap). The concept of OHRQoL is now used as an important parameter for measuring outcome in modern dentistry and medicine. It therefore means that OHRQoL can be considered as an indicator to assess the QoL of patient with SDA before and after restoration with distal extension RPD. Käyser in his study concluded that there was sufficient adaptive capacity to maintain adequate oral function in SDA when at least four occlusal units are left, preferably in a symmetrical position. [12] Similarly, a population-based study showed that SDA is not associated with negative impacts on QoL. [17] However, a study conducted among Japanese patients who have less than first molar contact reported significantly lower QoL. [18]

Most studies have shown no significant improvement in the overall health-related QoL of subjects most especially in the functional limitation domain after RPD treatment, [19],[20] another study by Gerritsen et al. [21] showed that the "clinical course in SDA plus RPD is unfavorable, especially when RPD-related interventions are taken into account." On the contrary, studies done in Japan found reduction in the OHRQoL for every missing occlusal unit. [18],[22] However, most of these studies were done in Europe and Asia where the diet is mainly processed and soft. Therefore, there is need to further investigate this pragmatic approach among Africans, especially Sub-Saharan Africans whose diets are usually coarse and fibrous in nature with a view to justify the use of the approach in Africa.

| Materials and Methods | |  |

A total of 36 patients attending the prosthetic outpatient dental clinic of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital with bilateral or unilateral free-end saddle with intact anterior regions and who can read and write in English were recruited into the study. The patients were those attending prosthodontic clinic for the first time and have no history of any systemic illness. Informed and written consent was obtained from each patient before the commencement of the study. The study was also approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital. Relevant history and demographic characteristics such as age, sex, and occupation were obtained from the subjects.

OHIP-49 was used for this study because it has been previously used and validated by Nigerian authors. [14] It measures seven conceptual dimensions of impact: (1) Functional limitation (e.g., difficulty with chewing), (2) physical pain (e.g. sensitivity of teeth) (3) psychological discomfort (e.g., self-consciousness), (4) physical disability (e.g., changes to diet), (5) psychological disability (e.g., reduced ability to concentrate), (6) social disability (e.g., avoiding social interaction), and (7) handicaps (e.g., being unable to work productively). This model is based on the WHO's international classification of impairments, disabilities, and handicaps in which impacts of disease are categorized in a hierarchy ranging from internal symptoms, apparently primarily to the individual (represented in the dimension of functional limitation), to handicaps that affect social roles, such as work/play. Each questionnaire item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale as such: 0 - never or not applicable, 1 - hardly ever, 2 - occasionally, 3 - fairly often, and 4 - very often. The coded responses were multiplied by the corresponding weight for each question, and products were summed within each dimension to give seven subscale scores, each with a potential range from 0 (no impact) to 40 (all impact reported). [15] A high score represented a low OHRQoL, and a low score represented a high OHRQoL.

The OHIP-49 questionnaire was completed by each of the patients before the commencement of treatment under the supervision of a trained and calibrated prosthodontist. Metal-based RPD's (chrome-cobalt) were fabricated by the same laboratory technician following the one-piece casting technique described by Knezović-Zlatarić et al. [23] A diagnostic cast made from a diagnostic impression was surveyed. This was to establish the path of insertion, guide planes, and to define the undercuts used to retain the denture. According to the designs made from the diagnostic cast, the necessary mouth preparations were carried out such as rest seats and sluiceway for the minor connectors. Preliminary impression and casts were made. The denture framework was modeled in wax on duplicated refractory casts. The wax pattern was sprued and then completely invested in the investment material in a split-casting ring. The wax was removed by the lost-wax technique in a furnace. The centrifugal casting technique was used to force the melted chrome-cobalt metal into the casting ring to make the metal framework. Altered cast technique was used to reduce the differential support for a free-end saddle by obtaining a compressive impression of the edentulous area underconditions, which mimic functional loading. The metal framework with an occlusal rim was used to record the correct jaw relationship. The waxed up denture was then invested in dental plaster, the wax boiled out, and the mold packed with heat cured acrylic after a separating agent has been applied. The fabricated RPDs were examined for completeness, fit, retention, and stability before being inserted into the patients' mouth. Instructions were given to the patients on the use and care of the partial dentures and in particular the need to maintain good oral hygiene. Various concerns of the patients were addressed before they left the clinic. Subjects were recalled 48 h, 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months postdenture insertion. On 3 months recall, the subjects were given another OHIP-49 questionnaire to evaluate their OHRQoL based on their experiences with the metal-based RPD's. The occupations of the subjects were categorized as social Class I, II, III, and IV using Arowojolu's classification. [24]

The data collected was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois USA 2010). The analysis was done using Chi-square and paired t-test was also performed on the subject's biodata and information related to tooth loss to ascertain their influence on the OHRQoL in the subjects. The significance of the test statistics was set at 0.05.

| Results | |  |

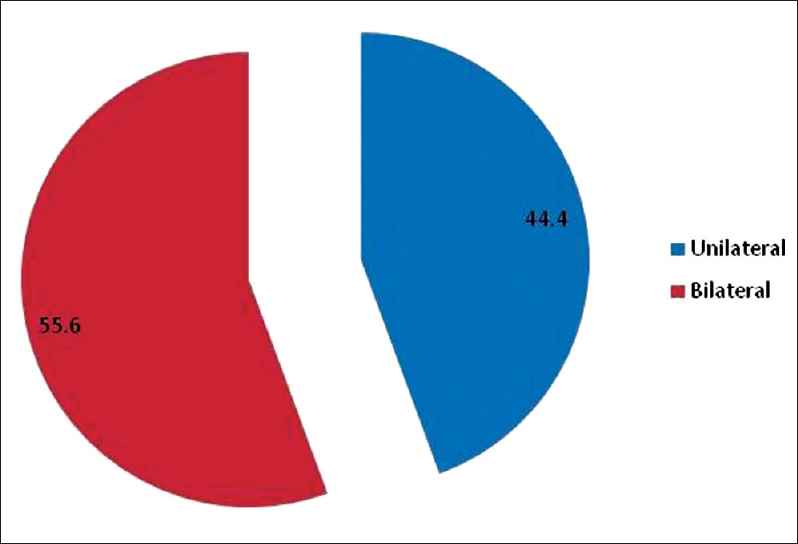

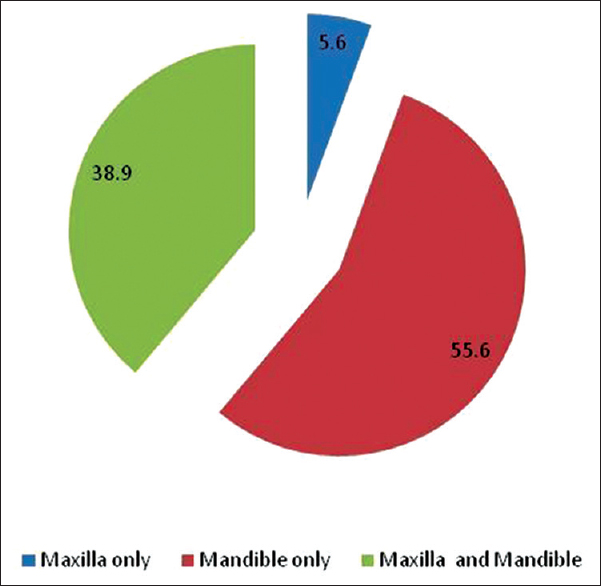

A total of 36 subjects comprising 24 (66.7%) females and 12 (33.3%) males, participated in this study. Their age ranged from 34 years to 64 years with the mean age being 52.2 ± 8.2 years. The majority 34 (92.2%) of the subjects were above 40 years [Table 1]. Twenty (55.6%) subjects had bilateral free-end saddle while 16 (44.4%) had unilateral free-end saddle [Figure 1]. In addition, 20 (55.6%) patients had free-end saddle in the mandibular arch only while 2 (5.6%) subjects had free-end saddle in the maxillary arch only. Fourteen (38.9%) subjects had free-end saddles in both maxillary and mandibular arches [Figure 2]. | Figure 1: Types of restored free-end saddle area among the subjects (percentages)

Click here to view |

| Figure 2: Distribution of treated dental arch among the subjects (percentages)

Click here to view |

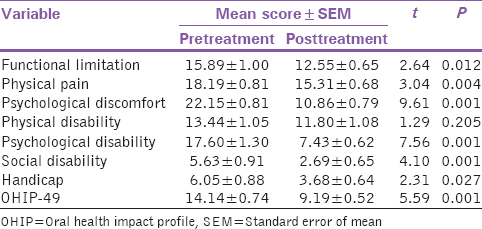

There was a significant improvement in the total OHIP-49 score 3 months after the insertion of the RPD. In addition, a significant improvement in all the domains except the physical disability was noted [Table 2]. | Table 2: Comparison of the mean scores of the different domains of oral health impact profile 49 before and after treatment

Click here to view |

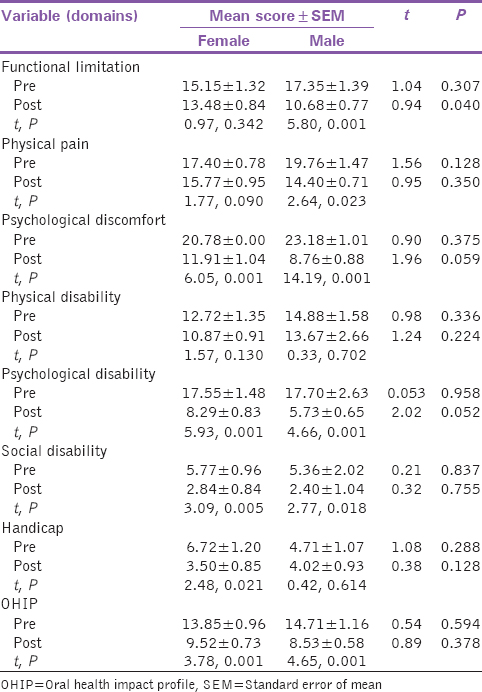

Irrespective of the gender, a significant improvement was observed in the post-OHIP score compared with the pre-OHIP score. However, in contrast with females, the males expressed the significant impact of treatment on the functional limitation and physical pain domains, whereas the females only expressed the significant impact of RPD on the handicap domain [Table 3]. | Table 3: The effect of gender on the oral health-related quality of life among the subjects at the pre- and post-treatment phase

Click here to view |

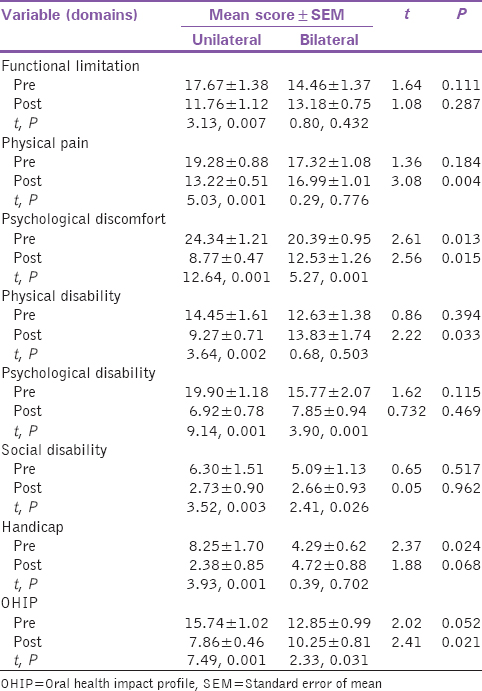

Irrespective of the saddle type, there was a significant improvement in the QoL of the subjects after treatment with RPD. Subjects with unilateral free-end saddle expressed significant improvement in all domains of OHIP-49 after treatment with RPD, whereas subjects with bilateral free-end saddle only expressed significant improvement in psychological discomfort and psychological disability domains [Table 4]. | Table 4: The effect of saddle type on the oral health-related quality of life among the subjects at the pre- and post-treatment phase

Click here to view |

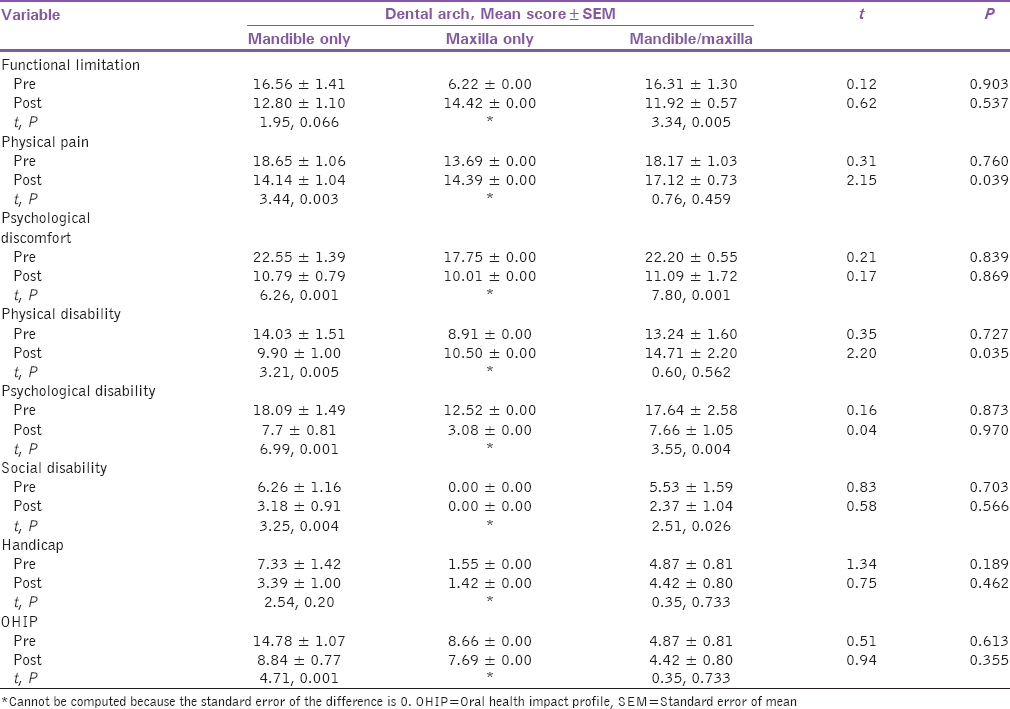

In general, there was a significant improvement in all the domains of OHIP-49 except in functional limitation and handicap domains after treatment with mandibular RPD only. However, patients treated with maxillary RPD only expressed the negative impact of treatment on their QoL in all domains except in psychological disability and discomfort domains. There was no significant improvement in the total OHIP-49 in subjects treated with both maxillary and mandibular RPD. However, significant improvement was expressed in functional limitation, psychological discomfort, psychological disability, and social disability domains in these subjects [Table 5]. | Table 5: The effect of type of dental arch on the oral health-related quality of life at pre- and post-treatment phase among the subjects

Click here to view |

| Discussion | |  |

The result of this study showed that treatment of SDA subjects with metal-based RPD improved their QoL. This finding though similar to some studies; [5],[25],[26],[27] however, differs from other studies. [28],[29] The improved OHRQoL, especially in the functional limitation domain after treatment with RPD may be attributed to satisfaction with their ability to chew and enjoy the meals they often labor to chew without dentures. Most of Nigerian foods are fibrous in nature such as roasted corn, roasted plantain, yam, and vegetables. In this clime, the ability to chew food properly is synonymous with satisfaction with the food. Regardless of our findings, patients' satisfaction with prosthesis may be a confounder. [30] Patients who are satisfied with their dentures generally reported improved OHRQoL. In addition, denture satisfaction and improved QoL after rehabilitation could also be dependent on better understanding of patient behavior and crucial communication between patients and practitioner. [31]

Significant improvement was expressed in the overall QoL by both males and females; however, varied results were observed at different domains. While the males expressed significant impact in the functional limitation and physical pain, the female expressed impact in the handicap domain. The reason for the difference is not clear, but it may be due to the preference of women for softer diet in our environment. Further studies need to be done to ascertain this.

Irrespective of saddle type (unilateral or bilateral free-end saddle), there was a significant improvement in the OHRQoL of the subjects after treatment with RPD. One might feel that the subjects with bilateral free-end saddle will express more impact on their OHRQoL than the unilateral subjects. The case was not so in this study. The subjects with unilateral expressed reduced impact of RPD treatment on OHRQoL than the bilateral free-end saddle subjects. The reason for this could be that subjects with unilateral free-end saddle (had natural teeth on the contralateral side of their arch) had better retention, support, and cross arch stabilization from the contralateral teeth. This will promote better and more effective functional ability. Also, the discomfort during occlusal loading of the free-end saddles, sensitivity of the abutment teeth due to eccentric loading, and/or denture kinetics might have contributed to the longer adaptation for bilateral free-end saddle compared to the unilateral free-end saddle. [20]

A search of literature on the effect of saddle type on the OHRQol in SDA subjects yielded no result. Further research is needed in this area.

The mandibular subjects expressed better OHRQoL with RPD treatment when compared with the maxillary subjects. The reason for this could be that the mandibular RPDs are aided by gravity and hence providing stable prosthesis, whereas the action of gravity will acts against the maxillary free-end saddle denture by displacing it off the ridge posteriorly while in function.

No significant improvement was seen in OHRQoL of subjects after treatment with both mandibular and maxillary free- end RPDs. The wearing of upper and lower dentures together may have been very uncomfortable for the patient; the tongue space might have been reduced consequently affecting the speech of the patients. In addition, the biting force may not have been satisfactory because of the compressibility of underlying mucosa usually associated with posterior mandible. [32]

A major limitation of this study is the low sample size which is due to the strict inclusion criteria for the study which are; intact anterior teeth, absence of molar teeth whether unilateral or bilateral free-end saddle and English literacy. Therefore, a study with larger sample size and of a longer follow-up period is needed to validate the conclusions of this study. In addition, it should be noted that OHRQoL questionnaire (OHIP-49) is a subjective tool; however, evidence has shown that it is effective in assessing the QoL measures.

| Conclusion | |  |

RPD treatment of one arch opposed by dentate arch significantly improved the overall OHRQoL of Nigerian subjects with SDA. However, no significant improvement was seen after treatment with both mandibular and maxillary free-end RPDs. Therefore, RPD treatment of an arch opposed by dentate arch may be suggested as a form of rehabilitation for such subjects, especially in patients who express concerns for chewing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| References | |  |

| 1. | Sheiham A. Public health aspects of periodontal diseases in Europe. J Clin Periodontol 1991;18:362-9.  [ PUBMED] |

| 2. | Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:126.  [ PUBMED] |

| 3. | Hultin M, Davidson T, Gynther G, Helgesson G, Jemt T, Lekholm U, et al. Oral rehabilitation of tooth loss: A systematic review of quantitative studies of OHRQoL. Int J Prosthodont 2012;25:543-52.  [ PUBMED] |

| 4. | Sarita PT, Witter DJ, Kreulen CM, Creugers NH. The shortened dental arch concept - Attitudes of dentists in Tanzania. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003;31:111-5.  [ PUBMED] |

| 5. | Wolfart S, Heydecke G, Luthardt RG, Marré B, Freesmeyer WB, Stark H, et al. Effects of prosthetic treatment for shortened dental arches on oral health-related quality of life, self-reports of pain and jaw disability: Results from the pilot-phase of a randomized multicentre trial. J Oral Rehabil 2005;32:815-22.  |

| 6. | Al-Quran FA, Al-Ghalayini RF, Al-Zu′bi BN. Single-tooth replacement: Factors affecting different prosthetic treatment modalities. BMC Oral Health 2011;11:34.  [ PUBMED] |

| 7. | Zlataric DK, Celebic A, Valentic-Peruzovic M, Panduric J, Celic R, Poljak-Guberina R. The influence of Kennedy′s classification, partial denture material and construction on patients′ satisfaction. Acta Stomat Croat 2001;35:77-81.  |

| 8. | Ramfjord SP. Periodontal aspects of restorative dentistry. J Oral Rehabil 1974;1:107-26.  [ PUBMED] |

| 9. | Käyser AF, Witter DJ, Spanauf AJ. Overtreatment with removable partial dentures in shortened dental arches. Aust Dent J 1987;32:178-82.  |

| 10. | Käyser AF. Limited treatment goals - Shortened dental arches. Periodontol 2000 1994;4:7-14.  |

| 11. | Witter DJ, van Palenstein Helderman WH, Creugers NH, Käyser AF. The shortened dental arch concept and its implications for oral health care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1999;27:249-58.  |

| 12. | Käyser AF. Shortened dental arches and oral function. J Oral Rehabil 1981;8:457-62.  |

| 13. | Witter DJ, Allen PF, Wilson NH, Käyser AF. Dentists′ attitudes to the shortened dental arch concept. J Oral Rehabil 1997;24:143-7.  |

| 14. | Okunseri C, Chattopadhyay A, Lugo RI, McGrath C. Pilot survey of oral health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional study of adults in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. BMC Oral Health 2005;5:7.  [ PUBMED] |

| 15. | World Health Organization. International Classification of Impairments Disabilities and Handicaps: A Manual of Classification. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980.  |

| 16. | Locker D. Measuring oral health: A conceptual framework. Community Dent Health 1988;5:3-18.  [ PUBMED] |

| 17. | Tan H, Peres KG, Peres MA. Do people with shortened dental arches have worse oral health-related quality of life than those with more natural teeth? A population-based study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2015;43:33-46.  [ PUBMED] |

| 18. | Baba K, Igarashi Y, Nishiyama A, John MT, Akagawa Y, Ikebe K, et al. Patterns of missing occlusal units and oral health-related quality of life in SDA patients. J Oral Rehabil 2008;35:621-8.  [ PUBMED] |

| 19. | Wolfart S, Müller F, Gerß J, Heyedcke G, Marré B, Böning K, et al. The randomized shortened dental arch study: Oral health-related quality of life. Clin Oral Investig 2014;18:525-33.  |

| 20. | Wolfart S, Marré B, Wöstmann B, Kern M, Mundt T, Luthardt RG, et al. The randomized shortened dental arch study: 5-year maintenance. J Dent Res 2012;91 7 Suppl: 65S-71S.  |

| 21. | Gerritsen AE, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. An observational cohort study on shortened dental arches - Clinical course during a period of 27-35 years. Clin Oral Investig 2013;17:859-66.  [ PUBMED] |

| 22. | Baba K, Igarashi Y, Nishiyama A, John MT, Akagawa Y, Ikebe K, et al. The relationship between missing occlusal units and oral health-related quality of life in patients with shortened dental arches. Int J Prosthodont 2008;21:72-4.  [ PUBMED] |

| 23. | Knezović-Zlatarić D, Nemet M, Baučić I. Laboratory fabrication procedures of a metal partial denture framework. Acta Stomatol Croat 2003;37:95-8.  |

| 24. | Arowojolu MO. Effect of social class on the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease. Niger Med Pract 2001;39:26-8.  |

| 25. | Jepson N, Allen F, Moynihan P, Kelly P, Thomason M. Patient satisfaction following restoration of shortened mandibular dental arches in a randomized controlled trial. Int J Prosthodont 2003;16:409-14.  [ PUBMED] |

| 26. | Kimura A, Arakawa H, Noda K, Yamazaki S, Hara ES, Mino T, et al. Response shift in oral health-related quality of life measurement in patients with partial edentulism. J Oral Rehabil 2012;39:44-54.  [ PUBMED] |

| 27. | Ikebe K, Hazeyama T, Takahashi T, Matsuda KI, Gonda T, Nokubi T. Masticatory performance and prostheses in subjects with shortened dental arches. Nihon Hotetsu Shika Gakkai Zasshi 2007;51:710-6.  [ PUBMED] |

| 28. | Fueki K, Yoshida E, Igarashi Y. A systematic review of prosthetic restoration in patients with shortened dental arches. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 2011;47:167-74.  |

| 29. | Armellini DB, Heydecke G, Witter DJ, Creugers NH. Effect of removable partial dentures on oral health-related quality of life in subjects with shortened dental arches: A 2-center cross-sectional study. Int J Prosthodont 2008;21:524-30.  [ PUBMED] |

| 30. | Yen YY, Lee HE, Wu YM, Lan SJ, Wang WC, Du JK, et al. Impact of removable dentures on oral health-related quality of life among elderly adults in Taiwan. BMC Oral Health 2015;15:1.  [ PUBMED] |

| 31. | Turker SB, Sener ID, Ozkan YK. Satisfaction of the complete denture wearers related to various factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009;49:e126-9.  [ PUBMED] |

| 32. | Michael CG, Javid NS, Colaizzi FA, Gibbs CH. Biting strength and chewing forces in complete denture wearers. J Prosthet Dent 1990;63:549-53.  [ PUBMED] |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Table 2]

[Table 1], [Table 3], [Table 4], [Table 5]

|