|

|

| REVIEW ARTICLE |

|

| Year : 2014 | Volume

: 2

| Issue : 3 | Page : 118-124 |

|

Orthodontic intrusion: A contemporary review

Nabil M Al-Zubair

Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Sana'a University, Sana'a, Yemen

| Date of Web Publication | 12-Sep-2014 |

Correspondence Address:

Nabil M Al-Zubair

Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Sana'a University, Sana'a

Yemen

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None  | Check |

DOI: 10.4103/2321-3825.140625

Orthodontic intrusion is a common treatment approach in managing orthodontic esthetic and functional problems, including gummy smile and deep bite. This review presents contemporary reports related to the intrusion, types of dental intrusion, clinical observations, and the tissue reactions after the application of intrusive force, as well as indications and contraindications for intrusion. This paper concisely describes the fixed and removable appliances used for intrusion accomplishment. Keywords: Biomechanics, intrusion arch, orthodontic intrusion

How to cite this article:

Al-Zubair NM. Orthodontic intrusion: A contemporary review. J Orthod Res 2014;2:118-24 |

| Contemporary Reports Related to the Intrusion | |  |

Intrusion is defined by Nikolai [1] as "a translational form of the tooth movement directed apically and parallel to the long axis", whereas Burstone [2] defined it as "apical movement of the geometric center of the root in respect to the occlusal plane or a plane based on the long axis of the tooth." Labial tipping of an incisor mound its center of resistance produces pseudointrusion, which can also correct the deep bite.

Dental intrusion often constitutes an integral part of orthodontic treatment in order to improve sagittal and vertical incisor relationships, to correct interincisal angle and consequently, the gingival line and restore the esthetics of smiling. [3]

In general, intrusion as an orthodontic therapeutic manipulation may mean: Orthopedic intrusion, surgical superior maxillary displacement, and intrusion of a single tooth or groups of teeth [Box 1 [Additional file 1]]. [4]

For many years, dental intrusion was considered impossible or problematic and was associated with numerous side-effects from the periodontium and cementum (root resorption). However, in recent years successful orthodontic intrusion is clinically documented and is considered a safe procedure, provided that the magnitude and direction of forces are carefully monitored. [5] Intrusion at the initial stages of treatment with or without auxiliary means is proposed independently of the therapeutic technique followed, such as Begg, tip-edge, or bioprogressive. [6],[7],[8]

| Types of Intrusion | |  |

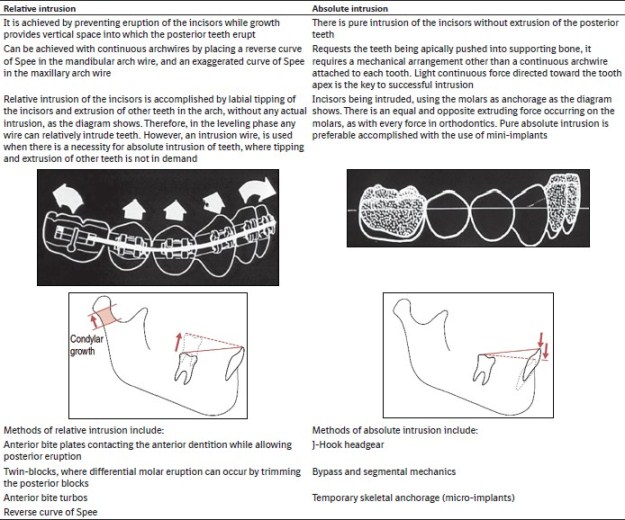

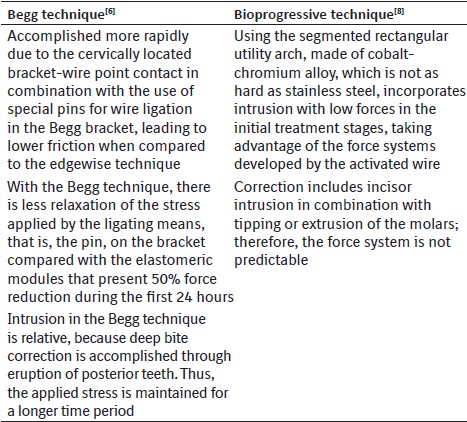

[9]

Clinical Observations and the Tissue Reactions after the Application of Different Orthodontic Forces[/TAG:2]

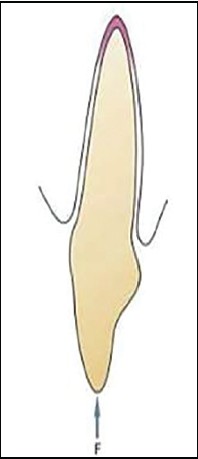

Intrusion of the tooth involves resorption of the bone, particularly around the apex of the tooth [Figure 1]. In this movement, the whole of supporting structures are under pressure with virtually no areas of tension. | Figure 1: Intrusion of the tooth involves resorption of the bone, particularly around the apex of the tooth

Click here to view |

Unlike extruded teeth, intruded teeth in young patients undergo only minor positional changes after treatment. Relapse usually does not occur, partly because the free gingival fiber bundles become slightly relaxed. Stretch is exerted primarily on the principal fibers. An intruding movement may therefore cause the formation of new bone spicules in the marginal region. These new bone layers occasionally become slightly curved as a result of the tension exerted by stretched fiber bundles. Such tension also occurs in the middle third of the roots. Rearrangement of the principal fibers occurs after a retention period of a few months. [10]

Intrusion requires careful control of force magnitude. Light force is required because the force is concentrated in a small area at the tooth apex. A light contentious force, such as that obtained in the light wire technique, has proved favorable for intrusion in young patients. In other cases, the alveolar bone may be closer to the apex, increasing the risk for apical root resorption. If the bone of the apical region is fairly compact as it is in some adults, a light interrupted force may be preferable to provide time for cell proliferation to start, and direct bone resorption may prevail when the arch is reactivated after the rest period. Intrusion may also cause changes in the pulp tissue such vascularization of the odontoblast and pulpal edema. [11]

| Biomechanical Methods of Orthodontic Intrusion | |  |

In the literature, intrusive force values vary among authors from 15 to 200 g. [12] This variation may be explained by the difficulty in measuring the force applied by complex biomechanical systems using continuous straight archwires, [12],[13] as well as by differences among various techniques.

However, continuous light forces of 15-30 g per tooth seem to be ideal. In general, heavier forces should be avoided given the fact that in this type of movement, the force is distributed over a small area around the apex. [14] Related studies have determined that forces exceeding 50 g lead to apical displacement of about 40 um resulting in vessel torsion or distortion. [15] Other studies have shown that force increase from 0.5 to 2 N results in reversible 20% reduction of blood circulation in the pulp. [16]

Higher loading at the apical area is related to intrusion, extrusion and rotation forces, whereas tooth translation and movement with tipping, apply the load along the whole length of the root or toward the cervical area. [17]

An important factor for successful incisor intrusion is the anatomical position of tooth roots in relation to the cortical plate. Maintaining roots in a proper position within spongeous bone and avoiding their displacement in cortical bone are considered to increase treatment effectiveness and limit the risk for root resorption. [18] However, it is generally accepted that certain techniques, such as the bioprogressive one, use root positioning of posterior teeth within cortical bone to increase anchorage and limit mesial molar movement. This hypothesis is not supported by research data.

| Intrusion Arch | |  |

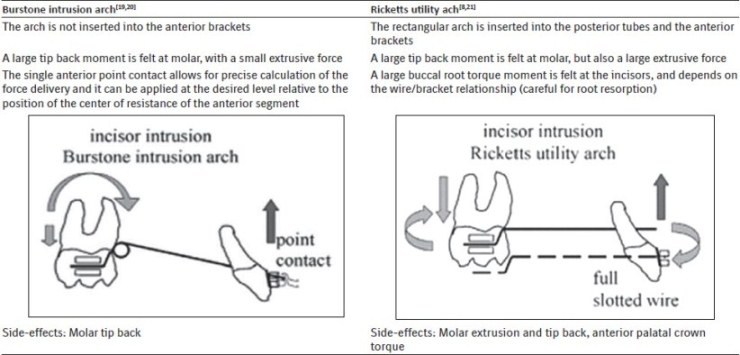

Two major orthodontic intrusion techniques for the anterior dentition have been developed: The segmented arch and the bioprogressive techniques. [2],[8],[19],[20],[21] Both use intrusion arches with anchorage on posterior teeth, but have fundamental biomechanical differences in their construction/use and consequently in their mode of action. [22]

Intrusion of Anterior Teeth in Gummy Smile

One of the major challenges of orthodontic treatment is the correction of deep overbite. In most instances, this correction is produced by the extrusion of posterior teeth, or a combination of anterior intrusion along with posterior extrusion, which is undesirable in vertical growers. [2] In such cases, absolute intrusion or true intrusion of the anteriors is desired, especially when there is excessive incisal display with extruded incisors.

More specifically, in cases where bite opening with orthodontic eruption of posterior teeth using biteplates or cervical headgear is contraindicated or unsuccessful, deep bite correction may only be achieved with intrusion of the anterior teeth. In order to improve esthetics, Class II, division 1 malocclusion patients with increased overjet and lower facial height, showing at the same time a gummy smile and incisor exposure at lip rest [Figure 2], considered as perfect candidates for such intrusion. [23] Since, it has been suggested that attractive smiles have zero gingival exposure, whereas gingival exposure of more than 2 mm results in significant esthetic, [24] deep bite correction with orthodontic eruption of posterior teeth does not contribute towards esthetic improvement.

Deep Bite and Reduced Lower Facial Height

The outcome of orthodontic eruption is not stable, especially in adult patients with a small mandibular plane angle and strong masticatory system as shown clinically by the presence of strong masseter muscles and a rectangular face, due to the increased vertical component of the biting force that affects the stability of posterior eruption. [5] On the other hand, in patients with severe deep bite and minimal exposure of incisors at smiling, correction should include careful intrusion of lower incisors in order to avoid further concealment of upper anterior teeth at smiling. Alternatively, and depending on the degree of deep bite, posterior orthodontic eruption with the use of an anterior biteplate is recommended and hence that part of the correction is achieved without intrusion.

Deep Bite and Increased Lower Facial Height

In the rare cases, where the dental deep bite is combined with a skeletal background of increased vertical growth and clinical "open bite tendency", posterior orthodontic eruption should be avoided due to an increase of the mandibular plane angle. [25]

Incisor intrusion is also necessary in cases of extrusion of maxillary but, especially, mandibular incisors often observed in Class II, division 2 malocclusion. In these cases, esthetic improvement is important mainly due to restoration of the gingival line. During intrusion of lower incisors with lingual tipping, using a utility arch without tie back, the incisor crown follows an arch and moves labially, while being vertically displaced. This horizontal crown displacement contributes towards correcting part of the over jet. [8] Similar movement with the same biomechanical principles takes place in the Begg technique, where once again the tie back is not recommended so as to avoid side-effects, such as root resorption. [6]

Intrusion of Periodontally Involved Teeth

The most common pathologic cause of extrusion is periodontal disease, which in advanced stages results in clinical crown lengthening and spacing of the teeth, thus, further compromising the esthetics of smiling. [26]

In general, orthodontic treatment in periodontal patients is a contradictory issue. Many authors dispute the benefits of such an approach and claim that it has negative effects on the periodontium, [27] whereas others support the view that orthodontic treatment inhibits the progression of osseous loss. [28] More recent studies conclude that a combination of periodontal treatment and orthodontic intrusion may improve periodontal status, given that the mechanics used and oral hygiene are carefully controlled. [29,30] More specifically, use of light orthodontic forces is recommended because, as bone loss progresses, periodontal support is reduced and the same force now induces greater stress on the periodontal ligament when compared to a tooth with normal tissue support. [31] Further documentation is necessary before these results and the hypothesis of re-attachment are applied in the clinical situation.

Intrusion of periodontally involved teeth still controversial, however, some authors pointed out that if the inflammation would be well monitored, the loss of the marginal bone level would not result. [32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37]

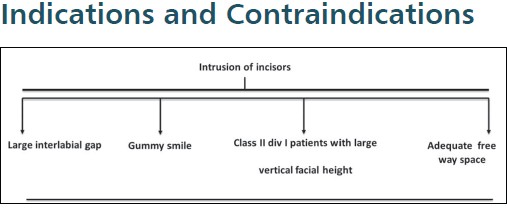

Intrusion of Posterior Teeth

Overeruption of maxillary molars because of the loss of opposite teeth creates occlusal interferes and functional disturbances [Figure 3]. To restore proper occlusion, intrusion of the overerupted molars becomes essential before multidisciplinary reconstructive dental approaches can be initiated. [35]

In general, the extent of intrusion depends on anchorage and may include absolute or relative intrusion, depending on the severity of the occlusal and esthetic problem.

Posterior intrusion is one of the most difficult tooth movements in orthodontics, because of the multiple molar roots. Intrusion requires more alveolar bone reaction as well as a longer treatment time. [38] Therefore, using conventional orthodontic treatment for this movement is a big challenge. Three-dimensional movement control is essential in this therapy. Vertical position, the arch form, the tooth axes, the inclination of the occlusal plane and the posterior torque should be the treatment objectives. [39] The use of orthodontic mini-implants simplified the treatment plan and allowed maximum conservation of tooth structures.

| The Fixed and Removable Appliances Used for Intrusion Accomplishment | |  |

In general, intrusion may be divided into two wide categories on the basis of the group of teeth on which it is applied:

- Incisor intrusion and

- Intrusion of posterior teeth.

The scope of orthodontics is expanding. Temporary anchorage devices have allowed the orthodontist to overcome anchorage limitations and perform difficult tooth movements predictably and with minimal patient compliance. [40]

Acrylic intrusion splint with occlusal and incisal coverage in combination with very high, almost vertical pull headgear [Figure 4] has been also proposed for the intrusion of anterior teeth. [23] This method corrects the position of anterior teeth sagitally and vertically and is indicated in Class II, division 1 cases where both incisor intrusion and reduction of increased overjet are required.

The use of magnets, as an alternative to conventional methods, has become popular after the introduction of new small, powerful and permanent rare earth magnets. Studies have shown that, when magnets are placed in the oral environment, saliva acts as an electrolyte creating small currents that stimulate tissues. [41] It has also been supported that the electromagnetic field created in the mouth with magnet movement increases vascularity and stimulates bone metabolism. [42] Orthodontic applications include samarium-cobalt (SmCo 5 , Sm 2 Co 17 ) and neodymium-iron-boron (Nd 2 Fe 14 B) magnets. [43] The latter deliver higher forces, but are more susceptible to demagnetization and corrosion. [44] [Table 1] concisely presents the basic means used for orthodontic dental intrusion.

| References | |  |

| 1. | Nikolai RJ. Response of dentition and periodontium to force. Bioengineering Analysis of Orthodontic Mechanics. Philadelphia: Lea and Febinger; 1985. p. 146-93.

|

| 2. | Burstone CR. Deep overbite correction by intrusion. Am J Orthod 1977;72:1-22.

|

| 3. | Gioka C, Eliades T. Orthodontic dental intrusion: Indications, histological changes, biomechanical principles, possible side effects. Hell Orthod Rev 2003;6:129-46.

|

| 4. | Marcotte MR. Biomechanics in Orthodontics. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1990.

|

| 5. | Proffit W, Fields H. Contemporary Orthodontics. 3 rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2000.

|

| 6. | Lew K. Intrusion and apical resorption of mandibular incisors in Begg treatment: Anchorage bend or curve? Aust Orthod J 1990;11:164-8.

|

| 7. | Bolendeà CJ. Orthodontic treatment of overbite by the Tip Edge technique in conjunction with an anterior bite elevator. Part 1. Orthod Fr 2001;72:375-86.

|

| 8. | Ricketts RM, Bench RW, Gugino CF, Hilgers JJ, Schulhof RJ. Bioprogressive Therapy. Denver, Colo: Rocky Mountain Orthodontics; 1979. p. 111-26, 188-99.

|

| 9. | Ng J, Major PW, Heo G, Flores-Mir C. True incisor intrusion attained during orthodontic treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005;128:212-9.

|

| 10. | Stenvik A, Mjör IA. Pulp and dentine reactions to experimental tooth intrusion. A histologic study of the initial changes. Am J Orthod 1970;57:370-85.

|

| 11. | Mostafa YA, Iskander KG, El-Mangoury NH. Iatrogenic pulpal reactions to orthodontic extrusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1991;99:30-4.

|

| 12. | Burstone CJ, Koenig HA. Force systems from an ideal arch. Am J Orthod 1974;65:270-89.

|

| 13. | Drenker E. Calculating continuous archwire forces. Angle Orthod 1988;58:59-70.

|

| 14. | Greenfield RL. Simultaneous torquing and intrusion auxiliary. J Clin Orthod 1993;27:305-18.

|

| 15. | Takahashi K, Kishi Y, Kim S. A scanning electron microscope study of the blood vessels of dog pulp using corrosion resin casts. J Endod 1982;8:131-5.

|

| 16. | Sano Y, Ikawa M, Sugawara J, Horiuchi H, Mitani H. The effect of continuous intrusive force on human pulpal blood flow. Eur J Orthod 2002;24:159-66.

|

| 17. | Rudolph DJ, Willes PM, Sameshima GT. A finite element model of apical force distribution from orthodontic tooth movement. Angle Orthod 2001;71:127-31.

|

| 18. | Parker RJ, Harris EF. Directions of orthodontic tooth movements associated with external apical root resorption of the maxillary central incisor. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;114:677-83.

|

| 19. | Burstone CJ. Rationale of the segmented arch. Am J Orthod 1962;48:805-22.

|

| 20. | Burstone CJ. The mechanics of the segmented arch techniques. Angle Orthod 1966;36:99-120.

|

| 21. | Ricketts RM. Bioprogressive therapy as an answer to orthodontic needs. Part II. Am J Orthod 1976;70:359-97.

|

| 22. | Davidovitch M, Rebellato J. Two-couple orthodontic appliance systems utility arches: A two-couple intrusion arch. Semin Orthod 1995;1:25-30.

|

| 23. | Orton HS, Slattery DA, Orton S. The treatment of severe ′gummy′ Class II division 1 malocclusion using the maxillary intrusion splint. Eur J Orthod 1992;14:216-23.

|

| 24. | Hunt O, Johnston C, Hepper P, Burden D, Stevenson M. The influence of maxillary gingival exposure on dental attractiveness ratings. Eur J Orthod 2002;24:199-204.

|

| 25. | Costopoulos G, Nanda R. An evaluation of root resorption incident to orthodontic intrusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996;109:543-8.

|

| 26. | Weiland FJ, Bantleon HP, Droschl H. Evaluation of continuous arch and segmented arch leveling techniques in adult patients - A clinical study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996;110:647-52.

|

| 27. | Zachrisson BU, Alnaes L. Periodontal condition in orthodontically treated and untreated individuals. II. Alveolar bone loss: Radiographic findings. Angle Orthod 1974;44:48-55.

|

| 28. | Eliasson LA, Hugoson A, Kurol J, Siwe H. The effects of orthodontic treatment on periodontal tissues in patients with reduced periodontal support. Eur J Orthod 1982;4:1-9.

|

| 29. | Melsen B, Agerbaek N, Eriksen J, Terp S. New attachment through periodontal treatment and orthodontic intrusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988;94:104-16.

|

| 30. | Cardaropoli D, Re S, Corrente G, Abundo R. Intrusion of migrated incisors with infrabony defects in adult periodontal patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001;120:671-5.

|

| 31. | Rabie AB, Deng YM, Jin LJ. Adjunctive orthodontic treatment of periodontally involved teeth: Case reports. Quintessence Int 1998;29:13-9.

|

| 32. | Misch CE. Contemporary Implant Dentistry. 2 nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998.

|

| 33. | Melsen B, Agerbaek N, Markenstam G. Intrusion of incisors in adult patients with marginal bone loss. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1989;96:232-41.

|

| 34. | Hoste S, Vercruyssen M, Quirynen M, Willems G. Risk factors and indications of orthodontic temporary anchorage devices: A literature review. Aust Orthod J 2008;24:140-8.

|

| 35. | Tseng YC, Hsieh CH, Chen CH, Shen YS, Huang IY, Chen CM. The application of mini-implants for orthodontic anchorage. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;35:704-7.

|

| 36. | Yao CC, Lee JJ, Chen HY, Chang ZC, Chang HF, Chen YJ. Maxillary molar intrusion with fixed appliances and mini-implant anchorage studied in three dimensions. Angle Orthod 2005;75:754-60.

|

| 37. | Seth V, Kamath P, Venkatesh MJ, Prasad R, Vishwanath AE. Micro-implants: Innovative anchorage concepts in orthodontics. Orthod Cyber J 2011, http://orthocj.com/2011/01/micro-implants-innovative-anchorage-concepts-in-orthodontics/.

|

| 38. | Lee JS, Kim JK, Park YC, Vanarsdall RL. Applications of Orthodontic Mini-Implants. Canada: Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.; 2007.

|

| 39. | Ohmae M, Saito S, Morohashi T, Seki K, Qu H, Kanomi R, et al. A clinical and histological evaluation of titanium mini-implants as anchors for orthodontic intrusion in the beagle dog. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001;119:489-97.

|

| 40. | Kravitz ND, Kusnoto B, Tsay TP, Hohlt WF. The use of temporary anchorage devices for molar intrusion. J Am Dent Assoc 2007;138:56-64.

|

| 41. | Davidovitch Z, Shanfeld JL, Montgomery PC, Lally E, Laster L, Furst L, et al. Biochemical mediators of the effects of mechanical forces and electric currents on mineralized tissues. Calcif Tissue Int 1984;36 Suppl 1:S86-97.

|

| 42. | Gerling JA, Sinclair PM, Roa RL. The effect of pulsating electromagnetic fields on condylar growth in guinea pigs. Am J Orthod 1985;87:211-23.

|

| 43. | Papadopoulos MA. Biological aspects of the use of permanent magnets and static magnetic fields in orthodontics. Hell Orthod Rev 1998;1:145-57.

|

| 44. | Hwang HS, Lee KH. Intrusion of overerupted molars by corticotomy and magnets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001;120:209-16.

|

[Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3], [Figure 4]

[Table 1]

|