|

|

| REVIEW ARTICLE |

|

| Year : 2016 | Volume

: 11

| Issue : 3 | Page : 97-100 |

|

A critical review for study proposal for medicine pricing in Sudan

Salah Ibrahim Kheder, Hassan Mohamed Ali

Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, National University, Khartoum, Sudan

| Date of Web Publication | 31-Aug-2016 |

Correspondence Address:

Salah Ibrahim Kheder

Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, National University, Khartoum

Sudan

| Check |

DOI: 10.4103/1858-5000.189591

In 2008, the Secretary of National Medicines and Poisons Board (NMPB) carried out a study that measured prices of drugs marketed in Sudan. The unpublished study reported that 23% in public sector and 38% in private sector of studied drugs were higher 10 times than international prices. The importance of the study that it's results in turn were used by Sudanese health policymaker as evidence that policies are needed to contain drug prices. In 2010, the NMPB issued a decree of medicine pricing and according to its regulations registered medicines in Sudan have been revised, and the importers were asked to reduce their prices between 15% and 80% of their registered cost and freight prices. In this review, we criticized and commented only on some conclusions and recommendations without going deeply in the methodological flaws that study suffer from. Keywords: Medicines pricing, Sudan, WHO report 2007

How to cite this article:

Kheder SI, Ali HM. A critical review for study proposal for medicine pricing in Sudan. Sudan Med Monit 2016;11:97-100 |

| Introduction | |  |

In 2008, the Secretary of National Medicines and Poisons Board (NMPB) carried out a study that measured prices of drugs marketed in Sudan. [1] The unpublished study reported that 23% in public sector and 38% in private sector of studied drugs were higher 10 times than international prices. The importance of the study that it's results in turn were used by Sudanese health policymaker as evidence that polices are needed to contain drug prices. In 2010, the (NMPB) issued a decree of medicine pricing, [2] and according to its regulations, registered medicines in Sudan have been revised, and the importers were asked to reduce their prices between 15% and 80% of their registered cost and freight prices. The (NMPB) study has been shown to have many comparative and methodological flaws which bias the results in favor of health authority. This is paper comments on some points of the NMPB study.

In the study, the author draw inappropriate conclusion from the WHO report (2007), [3] when he said that the medicine prices in Sudan are the highest among Mediterranean region, and some medicines prices were 18 times international reference price indicator guide (MSH 2008), [4] while in Kuwait which their health expenditure 152 $/capita, compared to Sudan 4 $/capita (WHO 2004b), [5] medicine prices only 5 times same indicator, and he conclude that this mainly due to the high profit of pharmaceutical companies markup on the medicine cost in addition to governmental taxes and fees which reach 23%.

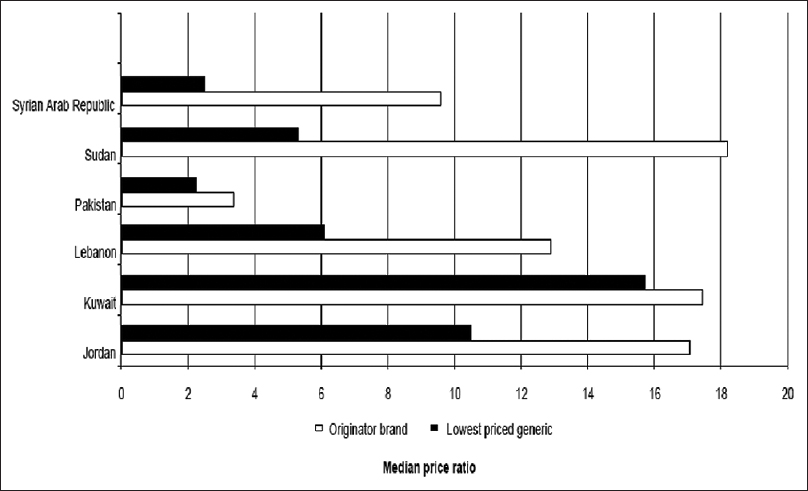

When we referred to the WHO report (2007) [3] and to the report of a survey of medicine prices in Kuwait (2005), [6] we found the following controversy results: First, in Sudan public sector, the generic procurement prices were observed to be acceptable (0.2) compared to Kuwait which procured originator brand (OB) name medicines at 5 times the MSH reference price and low price generic (LPG) at 1.2 times MSH reference prices which considered as "excessive" (in case of publicly procured generic medicines, prices are considered "acceptable" if they have a median price ratio [MPR] of 1 or <1, which mean that the prices of generic medicines are the same or less than the international reference prices). [3] Second, in Sudan private sector, only the OB medicines were 18 times the MSH reference price, whereas the generics were 5 times the same indicator, while in Kuwait, the prices in general are about 17 times the MSH reference price for both brand and generic medicines [Figure 1] (In case of private, if the MPR was found to be <2.5, it was considered "acceptable."). [3] Third, in the private sector at the retail pharmacy level, Sudan had the largest average brand premium (3.7) (meaning that the originator price was more than 3½ times the generic brand on average). While in Kuwait, the median brand premium was only 1.1, i.e. there is only a 10% price differential between OB and lowest priced generic medicines, which provides little incentive for patients to use generic medicines. The situation in Kuwait was considered a unique as only small price difference between prices of OB and LPG in private sector. This is in contrast with the international trends and with other countries in the region and saving the money by switching to LPG equivalents. | Figure 1: Median price ratio for medicines in private sectors in some Mediterranean countries

Click here to view |

Fourth, generic medicines do not have the same research and development costs as innovator brand medicines, and they should be available at much lower prices as a result. The small difference between OB and generic medicines MPRs in Kuwait is probably an indication of generic medicines having their selling prices based on the selling price of brand medicines rather than the actual costs of manufacture. It could be argued that this is a result of low prices of brand-name medicines, but the magnitude of the innovator brand MPRs (summary MPR 17.5 relative to MSH prices) suggests that the medicines are in fact very expensive and considered to be the result of pricing regulations forces in Kuwait. [3],[6]

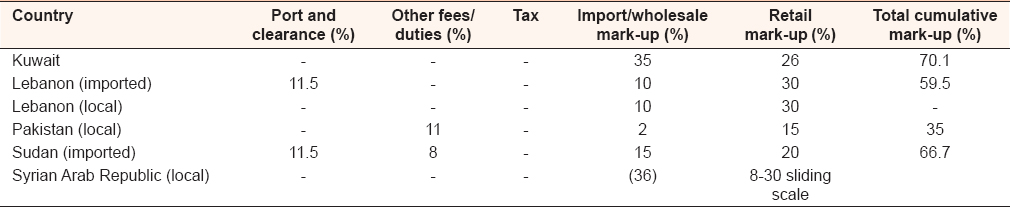

Fifth, in Kuwait generic, ciprofloxacin costs 125 times more in the private sector more than the public sector (MPR 100 vs. 0.8, respectively). The private sector price is the price the patients pays, whereas the public sector is a bulk procurement price; however, this does indicate that the price in the private sector is excessive, containing more than reasonable profit over the production, and research and development costs. In Kuwait, the wholesale markup 35% was more than the markup at the retail level, 26%, whereas in Sudan, the wholesale markup, 15% and retail markup, 20%. At the same time, various fees, duties, and/or taxes are levied on imported medicines (tax on sick), whereas import tariffs were not levied by Kuwait [Table 1]. | Table 1: Prices component summary for medicines in private sectors in some Mediterranean countries

Click here to view |

The study recommended that a ceiling price for originator should be settled, and this is determined by its therapeutic value and by set a reference price for originator such as its prices in the British National Formula or its median prices in Gulf countries. A price control to the registered generics is also had been recommended that is it should be <30%, than the OB price and this percentage decreased by a constant rate according to source and recommend the World Bank income classification.

The welfare implications of price control and reference prices cannot be established unconditionally for all markets as they depend on the market structure and balance of power between suppliers and buyers in each market. However, it is evident that whenever there are price controls, manufacturers invest resources in lobbying and other influence activities to maintain the regulated prices. These are wasted the resources and lead to welfare loss. [7] On the other hand, several surveys studies have been conducted on the ex-manufacturer prices and prices of essential drugs across countries with varying incomes do not find any significant correlation between price and per capita gross national product or any other proxies for income. [8],[9],[10],[11],[12] [Figure 2] shows the average prices for a basket of generic and branded medicines in low-, lower middle-, and upper middle-income countries. It is evident that there is little correlation between the price paid and the income class of the country.

| Discussion | |  |

The objective of any prices intervention should be to reduce prices with increased availability and improved affordability and access to needed medication. The development of pharmaceutical expenses has to be seen in a wider economic context. Curbing expenses are not always the right policy choice. If the population suffers from diseases that have a negative economic impact and are avoidable by providing drug treatment (for example malaria), such treatment should be made available through additional funding. The costs of avoidable complications need to be weighed against the costs of treatment, to assess the cost-effectiveness of incremental spending for drugs. [13]

A variety of pricing models for pharmaceuticals are used in different countries: [14]

- Free pricing: No regulatory intervention at the pricing level. The government or health-care provider tries to influence drug costs on the demand side through restricted reimbursement and/or market mechanisms such as public tenders or supply contracts

- Country of origin-based pricing: The manufacturer or importer provides data on the price in the country in which the drug is manufactured. This price is either the basis for negotiations or is entered into a formula to set the list price for the given country. In today's world of globalized supply chains, this approach is outdated: In several typical "countries of origin," manufacturers have significant economic power and can negotiate relatively high prices, making the model economically ineffective

- External reference pricing: The manufacturer provides (or the price setting authority obtains independently) price information from a number of countries that have been selected as reference standard. Then, a formula is applied to compute the list price. This model is used in many developed and middle-income countries. The issues are in the details: Currency fluctuations, inflation rates, and different market conditions in the reference countries can lead to distortions.

On a general note, all pharmaceutical policy choices have their up- and downsides and create reactions in the markets that are not necessarily predictable. What is important is a clear vision for the midterm policy goals and the tricky balance between cost containment, health outcomes, and economic benefits for the system as a whole and the "comfort factor" of having access to modern treatment alternatives even if these are not essentially better in terms of outcome. Under the umbrella of this longer term vision, however, specific policies and administrative measures need to be adaptable without too much "institutional pain" in case they lose their desired effect over time. Every strategy has to consider the options for monitoring of provider and patient behavior in a given system - we can only influence what we can measure - and balance incentives carefully to minimize unwanted consequences. Furthermore, cost-containment strategies should be built as modular, dynamic solutions that are regularly reviewed and updated to remain effective. [15]

In this review, we comment only on some conclusions and recommendations without going deeply in the methodological flaws that study suffer from. As general, price regulation system should be easy and not expensive to administer. It should also be objective, transparent, and predictable, meaning that there is limited room for regulator's discretion and all parties affected, particularly suppliers, are able to predict prices that will be granted and take their decision accordingly. If the outcome of the regulation is difficult to predict, suppliers are forced to take decisions with a higher uncertainty, which in the end means they will be less likely to make certain investment. Whenever a new policy is introduced, it is important to monitor the impact change to detect unintended consequences.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| References | |  |

| 1. | Gamal KM, Yagoub A. A proposal for medicines pricing in Sudan. National Medicine and Poison Board study; 2008. p. 2-21.  |

| 2. | |

| 3. | WHO 2007. Technical Discussion on Medicine Prices and Access to Medicines in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Mediterranean Region. EM/RC54/Tech. Disc. Hummad AT. (FMOH). Sudan Pharmaceuticals Country Profile; 2010. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/emp/media/pdf/EMRC54TECHDISC01en.pdf.  |

| 4. | MSH. International Price Indicator Guide; 2008. Available from: http://www.msh.org/resources/publication/IDPIG_2003html.  |

| 5. | WHO. The world medicines situation. WHO/EDM/PAR/2004.5. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.  |

| 6. | |

| 7. | Yadav P. Differential pricing for pharmaceuticals. A study conducted for the U.K Department for International Development (DFID); 2010. Available from: http://www.haiweb.org/medicineprices.  |

| 8. | Scherer FM, Watal J. Post-TRIPS options for access to patented medicines in developing nations. J Int Econ Law 2002;5:913-39.  |

| 9. | Maskus KE, Ganslandt M. Parallel imports, demand dispersion, and international price discrimination. J Int Econ 2002;37:187-96.  |

| 10. | Hellerstien R. Do Pharmaceutical Firms Price Discriminate Across Rich and Poor Countries? Evidence from Antiretroviral Drug Prices. Research Report Federal Reserve Bank of New York; 2004.  |

| 11. | Lai R, Yadav P. What Explain Prices of Pharmaceutical Purchased by Developing Countries? Working Paper 2008. MIT - Zaragoza International Logistics Program (October 2008); 2007.  |

| 12. | Waning B, Kaplan W, King AC, Lawrence DA, Leufkens HG, Fox MP. Global strategies to reduce the price of antiretroviral medicines: Evidence from transactional databases. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:520-8.  |

| 13. | |

| 14. | |

| 15. | Pharmaceuticals: Cost Containment, Pricing, Reimbursement: HNP Brief #7; August, 2005.  |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2]

[Table 1]

|