|

|

| CASE REPORT |

|

| Year : 2015 | Volume

: 7

| Issue : 1 | Page : 23-27 |

|

|

Propeller flap for complex distal leg reconstruction: A versatile alternative when reverse sural artery flap is not feasible

Samuel A Ademola, Afieharo I Michael, Femi J Oladeji, Kefas M Mbaya, O Oyewole

Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

| Date of Web Publication | 29-Jun-2016 |

Correspondence Address:

Samuel A Ademola

Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, University College Hospital, Ibadan

Nigeria

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None  | Check |

DOI: 10.4103/2006-8808.184943

Abstract Abstract | | |

Reverse sural artery fasciocutaneous flap has become a workhorse for the reconstruction of distal leg soft tissue defects. When its use is not feasible, perforator-based propeller flap offers a better, easier, faster, and cheaper alternative to free flap. We present our experience with two men both aged 34 years who sustained Gustilo 3B injuries from gunshot. The donor area for reversed sural artery flap was involved in the injuries. They had early debridement, external fixation, and wound coverage with perforator-based propeller flaps. The donor sites were covered with skin graft. All flaps survived. There were minor wound edge ulcers due to the pressure of positioning that did not affect flap survival and the ulcers healed with conservative management. Perforator-based propeller flap is a versatile armamentarium for reconstruction of soft tissue defects of the distal leg in resource-constrained settings, especially when the donor area for a reverse flow sural flap artery is involved in the injury. Keywords: Flap, perforator flap, propeller flap, reconstruction

How to cite this article:

Ademola SA, Michael AI, Oladeji FJ, Mbaya KM, Oyewole O. Propeller flap for complex distal leg reconstruction: A versatile alternative when reverse sural artery flap is not feasible. J Surg Tech Case Report 2015;7:23-7 |

How to cite this URL:

Ademola SA, Michael AI, Oladeji FJ, Mbaya KM, Oyewole O. Propeller flap for complex distal leg reconstruction: A versatile alternative when reverse sural artery flap is not feasible. J Surg Tech Case Report [serial online] 2015 [cited 2018 Jul 1];7:23-7. Available from: http://www.jstcr.org/text.asp?2015/7/1/23/184943 |

Introduction Introduction | |  |

Reconstruction of soft tissue defects in the distal third of the leg pose challenges for reconstruction as a result of the paucity of donor tissue, bony prominence at the medial and lateral malleolus, and relatively poor blood supply of the region.[1],[2] Random pattern flaps raised in the leg are limited in reliability, size, reach, and arc-of-rotation.[1],[3],[4] Most major injuries of the distal leg are associated with significant soft tissue defects because the tibia is mostly subcutaneous anteromedially. There is also less muscle bulk around its lower third.

Reverse sural artery fasciocutaneous flap has become a workhorse for the reconstruction of distal leg soft tissue defects in settings with limited resources.[5] Its use obviates the need for sophisticated equipment, extended operative time, and super specialized training. Revere sural artery flap is a relatively easy and fast method of transferring a large amount of tissue. It allows for good hemostasis, and it has a short learning curve.

When the vascular supply to this flap is injured as found in our patients, reliable options for reconstruction in the distal third of the leg becomes limited.

Free tissue transfer would have been another modality to choose; however, microsurgical skills, specialized equipment, cost, steep learning curve, and prolonged operating time required for this modality reduces its feasibility in our practice setting and even outside tertiary care centers in more developed countries.[1]

Perforator-based flaps address these problems. They afford speed,[3],[6] simplicity, color and texture match, lower cost, and allow greater arc of movement. Its applicability is possible in most parts of the body. Successful outcomes have been described in the axilla, periolecranon, forearm, lower extremity,[1] hand,[6] and trunk.[7] In spite of the versatility of perforator-based flaps, literature search reveals that report of its use is sparse from our practice setting.

We therefore present our experience with the use of three (tibioperoneal system) perforator-based propeller flaps in the reconstruction of distal leg defects following gunshot injuries. Perforator-based propeller flap provides a reliable option for resurfacing soft tissue defects when other options are not feasible.

Anatomy of distal leg perforators

Perforators are small diameter vessels that originate from a main pedicle and perforate the fascia or muscle to reach the skin. The development of flaps based on perforators has followed the understanding of the blood supply from a source artery to the skin.[8],[9] Anatomical studies have revealed that they emerge from the crural fascia in four longitudinal rows within the intermuscular septa that border the compartments of the lower leg and the tibia. They are grouped into clusters of perforators with consistent distance proximal to the intermalleolar line. In the leg, there are anterior tibial artery perforators; posterior tibial artery perforators, peroneal artery perforators, and sural artery perforators.[8]

Case Reports Case Reports | |  |

Two men both aged 34–year-old of different addresses at different incidences, were shot in the distal aspect of the left leg.

Case 1

The first patient was attacked by armed robber; he sustained Gustilo 3B open fractures with two soft tissue defects: A lateral one measuring 12 cm × 7 cm and a medial defect 14 cm × 6 cm [Figure 1] with injury to the recurrent sural artery precluding the use of the reversed sural artery flap for wound coverage. The distal part of the tibia and injured tendons were left exposed in the wound bed. He had initial wound debridement and application of external fixators to immobilize his fractures. He subsequently had wound coverage with two perforator-based propeller flaps raised from the medial and lateral aspect of the leg [Figure 2]. The secondary defects were covered with split-thickness skin graft. During the postoperative period, he developed seroma under the lateral flap which was drained and did not have any adverse effect on flap survival. He also developed a Grade 2 pressure ulcer on the lateral edge of the wound due to limb positioning. This healed without surgical intervention. Skin graft take was 100%. [Figure 3] shows the surgical outcome six weeks postoperatively.

Case 2

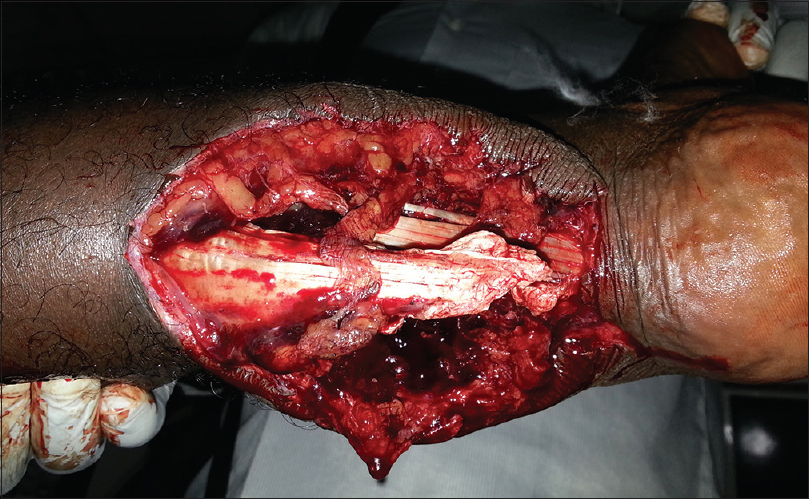

The second patient was shot during an argument; he sustained Gustilo 3B open fractures. The entry wound was quite small, but the exit wound located posteriorly measured 14 cm × 11 cm and a large portion of the Achilles tendon was exposed. The sural artery was found severed in the wound [Figure 4]. He had wound debridement, fracture reduction, and immobilization with an external fixator. A perforator-based propeller flap was raised to cover the wound and split thickness skin graft was applied to the secondary defect [Figure 5]. Flap survived without any area of loss [Figure 6]. The pins of the external fixator became loosened the 10th postoperative day, and the wound had to be manipulated to tighten the loose component. He developed hematoma in the wound after the procedure. This was drained with removal of the staples around the hematoma and the wound healed satisfactorily thereafter. Skin graft take was 100%. | Figure 4: Preoperative picture showing exposed Achilles tendon. The cavitation effect of the gunshot damaged the sural artery

Click here to view |

Flap design and surgical technique

Perforators in the proposed donor tissue close to the defect were located preoperatively using handheld Doppler (probe) and marked on the skin using methylene blue [Figure 7]. The flaps were then designed like blades of a propeller adjacent to the defects. The proximal end of the flap to the targeted perforator is made equidistant from the distal end of the defect to the perforator. | Figure 7: Preoperative planning showing the flap outline. Identified perforators were marked as x on the outline

Click here to view |

The flap sizes were made to be 0.5 cm more than the size of the defect to be covered to aid closure without tension.

An exploratory skin incision was made and carried through to include the deep fascia. Through this incision, blunt dissection in the subfascial plane was done to isolate the perforator. As soon as the adequacy of the perforator is assured, the other incisions were completed, and other perforators that would not be used were ligated. Fascial strands were released to allow for mobilization of the flaps and to avoid tension on the pedicle during the transfer. The flaps were rotated 180° into place like a propeller blade avoiding kinking of the perforator. Hemostasis was secured with diathermy and tourniquet without exsanguination was used for the first patient, but diathermy and ligatures were used for the second patient. Flaps were inset and secured using skin staples.

The sizes of the secondary defects were reduced by suturing and the remaining defect skin grafted. Primary closure was not possible in all the donor sites due to the size of flaps harvested. Bedside, flap monitoring was achieved via a window created within the dressing to examine the flaps.

Discussion Discussion | |  |

Soft tissue reconstruction of the distal third of the leg has been known to pose a challenge to the reconstructive surgeon. The distal third of the leg is easily exposed to trauma, and the soft tissue bears the brunt. There is an increase in the incidence of such defects in our practice setting due to change in the mode of commercial transportation and security challenges.[5] The distal leg is often a target of gunshot by an attacker without intent to kill.[10] Our patients belong to this group. Majority of the open fractures in this region are associated with significant soft tissue defect that will require reconstruction to protect the bones or implant devices in this part of the body; it may also be part of a limb salvage procedure in a complex extremity injury that requires skeletal stabilization, soft tissue, and vascular reconstruction.[11]

The sural artery could be injured in many cases of complex lower limb injuries precluding the reversed sural artery flap for reconstruction in such situations. The two patients that we presented both sustained injury to the sural artery and therefore the use of reverse sural artery fasciocutaneous flap recommended as a simple flap for reconstruction of soft tissue defect of the distal third of lower limb was not possible.[2],[5] As stated by Pirwani et al.[2] that irrespective of etiology, coverage of exposed soft tissue done in time is mandatory and essential for prevention of complications. It is a practice in our department to reconstruct soft tissue defect early except otherwise indicated. Soft tissue reconstruction in the first patient was delayed as it could not be done at the time of wound debridement and bone stabilization. This might have impacted on the subsequent clinical course as he had a longer clinical course and he had wound discharge for some weeks after flap surgery even though this did not affect flap survival.

The use of handheld Doppler-aided localization of perforators and made flap planning easy.[3],[4],[8] Once good Doppler ultrasonic signal signifying the presence of adequate perforator is detected, the planning and execution of the procedure were as easy and quick as with reverse sural fasciocutaneous flap [1],[3],[6] and can be easily be done by any trained reconstructive surgeon. In our patients, we ensured presence, safety, and adequacy of the perforators used via the exploratory incisions before making incisions on the opposite sides of the flap.

Perforator-based propeller flap offers numerous advantages. It is a one stage operation, which does not require microsurgical techniques. Elevation of the flap is easy and quick, provides an ideal tissue match, had minimal donor site morbidity, and seemed a simple and elegant solution.[1]

Many authors prefer the use of reverse sural artery flap for the reconstruction of the distal lower limb where feasible because of the disadvantages associated with free flap.[5] A local perforator-based propeller flap equally offers these same benefits over free flap, in addition to ease and speed of harvest, easy learning curve; closer and supple match and above all affordability in our setting.

Propeller flaps are also versatile. The flaps in our patients survived postoperative problems that could be caused by seroma, hematoma, pressure of position, and postoperative external fixator adjustment. These may not be achieved in other types of flaps such as a random pattern fasciocutaneous flap because their blood supply may not be as robust as that of perforator-based propeller flap. Some commonly documented complications of propeller flaps such as venous congestion, flap tip necrosis, and partial loss [3],[4] were not seen in our patients. Some postoperative problems noted in the patients deserve special attention so that such could be avoided in patients with similar reconstructions. The two patients developed hematoma postoperatively. It is possible that this complication could have been obviated if we used wound drains at surgery. Sparsity of literature reports on the use drains after propeller flap closure of posttraumatic lower limb defect could however suggest that it is not often required in these types of surgical closures of defects.

The pressure ulceration that occurred was probably due to the difficulty in positioning the limb as a result of multiple flaps that were raised in the patient and the logistics of limb positioning after application of external fixators for bone stabilization. It resolved as soon as pressure was relieved. Use of pressure relieving devices could have prevented this from occurring. However, the absence of venous congestion, tip necrosis, or partial flap loss in our patients was worthy of note. In our opinion, adequate fascial clearance to prevent vessels kinking and postoperative limb elevation might be contributory to the versatility of the flaps and prevention of these complications. However, this conclusion could not be made from these few cases.

All donors sites were skin grafted in this work due to larger size of the secondary defects when compared to the works of other authors [1],[3],[4],[6] who were able to achieve primary closure of the donor sites.

Conclusion Conclusion | |  |

Perforator-based propeller flap, with the numerous benefits that accompany its use, is a reliable, versatile armamentarium for the reconstruction of soft tissue defects of the distal leg in resource-constrained setting, especially when the perforators of the reverse sural artery flap have been injured.

Acknowledgment

We thank Professor O. M. Oluwatosin, Dr. O. A. Olawoye, and Dr. A. O. Iyun for technical advice and participation in the management of the patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References References | |  |

| 1. | Rad AN, Singh NK, Rosson GD. Peroneal artery perforator-based propeller flap reconstruction of the lateral distal lower extremity after tumor extirpation: Case report and literature review. Microsurgery 2008;28:663-70.  |

| 2. | Pirwani MA, Samo S, Soomro YH. Distally based sural artery flap: A workhorse to cover the soft tissue defects of lower 1/3 tibia and foot. Pak J Med Sci 2007;23:103-7.  |

| 3. | Karki D, Narayan RP. The versatility of perforator-based propeller flap for reconstruction of distal leg and ankle defects. Plast Surg Int 2012;2012:303247.  |

| 4. | Georgescu AV. Propeller perforator flaps in distal lower leg: Evolution and clinical applications. Arch Plast Surg 2012;39:94-105.  |

| 5. | Olawoye OA, Ademola SA, Iyun K, Michael A, Oluwatosin O. The reverse sural artery flap for the reconstruction of distal third of the leg and foot. Int Wound J 2014;11:210-4.  |

| 6. | Hao PD, Zhuang YH, Zheng HP, Yang XD, Lin J, Zhang CL, et al. The ulnar palmar perforator flap: Anatomical study and clinical application. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2014;67:600-6.  |

| 7. | Wettstein R, Weisser M, Schaefer DJ, Kalbermatten DF. Superior epigastric artery perforator flap for sternal osteomyelitis defect reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2014;67:634-9.  |

| 8. | Ignatiadis IA, Georgakopoulos GD, Tsiampa VA, Polyzois VD, Arapoglou DK, Papalois AE. Distal posterior tibial artery perforator flaps for the management of calcaneal and Achilles tendon injuries in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Diabet Foot Ankle 2011;2:7483.  |

| 9. | Schaverien M, Saint-Cyr M. Perforators of the lower leg: Analysis of perforator locations and clinical application for pedicled perforator flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;122:161-70.  |

| 10. | Shooting to Wound. Police Fire Arms Officers Association (PFOA), United Kingdom; A special Report. Available from: . [Last cited on 2015 Mar 10].  |

| 11. | Kadam D. Limb salvage surgery. Indian J Plast Surg 2013;46:265-74.  [ PUBMED]  |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3], [Figure 4], [Figure 5], [Figure 6], [Figure 7]

|