|

|

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

| Year : 2014 | Volume

: 9

| Issue : 1 | Page : 19-30 |

|

Evaluating medicines prices, availability, affordability and price components in Sudan

Salah Ibrahim Kheder1, Hassan Mohamed Ali2

1 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, National University, Khartoum 11111, Sudan

2 Department of Pharmacology, National University, Khartoum 11111, Sudan

| Date of Web Publication | 13-Nov-2014 |

Correspondence Address:

Salah Ibrahim Kheder

National University, Faculty of Pharmacy Khartoum, Sudan, 3783 Khartoum

Sudan

| Check |

DOI: 10.4103/1858-5000.144655

Background: The aim of this study to measure medicines prices, their availability, affordability and price structure carried out in different sectors in Sudan. Methods: A field study was undertaken in the public and private sector in Sudan from March 2012 to April 2013 using a standardized methodology developed by the (World Health Organization) and (health action international). Results: Based on median price ratio (MPR), the central medical store was procuring lowest priced generics (LPGs) at 1.2 times their international reference price (IRP), while they were selling generics at 2.34 times the IRP. The revolving drug fund was procuring LPGs at 1.55 times IRP, and selling generics at 5.13 times the IRP. In public pharmacies, the median MPR for LPG medicines was 2.99 and 8.03 for originator brands (OBs). In private retail pharmacies, the median MPR is 3.84 for LPGs and 19.37 for OBs. Generic medicines were the predominant products in public and private pharmacy sectors (39.5% and 56.6% respectively), while for OBs were 1.8% in public sector pharmacies and 9.3% for private pharmacy sector. The affordability of LPGs in the public sector was good for half of conditions, with standard treatment costing a days' wage or less for 53.3% of treatments. In the private sector, the affordability of LPGs was similar to the public sector. The government worker would have to work 2.5 days to pay for 1-month of treatment with OB Glibenclamide for diabetes when purchased from private pharmacies, for LPG Glibenclamide he has to pay about half-a day's salary to buy the medicines from public and private sectors. Conclusion: In Sudan, the availability of the surveyed medicines was low in all sectors as both OBs (<10%), and 40-50% as generics depending on the sector. LPGs have been accepted in the country as they are more available than OBs. In both the private and public sectors, considerable price differences were seen between OBs and LPGs. Medicines are often unaffordable for ordinary citizens. Keywords: Affordability, availability, health action international, medicines price, Sudan

How to cite this article:

Kheder SI, Ali HM. Evaluating medicines prices, availability, affordability and price components in Sudan. Sudan Med Monit 2014;9:19-30 |

| Introduction | |  |

0Measuring medicines prices

Medicines account for 20-60% of health spending in low- and middle-income countries, compared with 18% in countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. In developing countries, up to 90% of the population buy medicines through out-of-pocket payments, making medication the largest family expenditure item after food. [1] Drug prices and drug expenditures have become a major issue in the past few years in developing countries and health care policy makers are concerned that their countries are carrying a heavier burden than others in paying for drugs. Governments use a variety of approaches to try to control the cost of drugs and make sure that essential medicines are affordable and not overpriced. Measuring and understanding the medicines prices situation is the first stage in developing medicines pricing policies that would ensure availability and affordability. [2] Despite the fact that several stakeholders recognize medicines prices are an issue; the issue could not be addressed in a systematic manner in the past due to lack of a reliable methodology. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) and health action international (HAI) have undertaken a commendable task to address methodological difficulties in surveying medicine prices. [3]

Background - Sudan

Sudan is an Eastern Mediterranean country covering an area of 1,839,542 km 2 . In Sudan's 2008 census, the population of Northern, Western and Eastern Sudan and after the secession of South Sudan was recorded to be 33.9 million. [4] The country's administrative state is divided into 15 states, each state with a capital city and different small cities and rural provinces. Sudan is classified as a low-income country, with GNI per capita of US$ 1.511 [5],[6] and General Directorate of Pharmacy (GDP) growth rate 8.3% and annual population growth of 2.1%. The life expectancy at birth for men is 57 years and for women is 58 years. [7] The infant mortality rate is 56.9/1,000 live births. For children under the age of 5, the mortality rate is 78.4/1000 live births. The maternal mortality rate is 215.6/100,000 live births. [8],[9] The total health expenditure is 6.2% of the GDP. In Sudan, the total annual expenditure on health (THE) in 2010 was SDG (Sudan Pound) 7,886.5 million (US$ 3,755.5 million) 257 (US$ 122). [10] The government annual expenditure on health accounts for 27.8% of the total expenditure on health, [11] with a total per capita public expenditure on health of SDG 71 (US$ 33.9). The government annual expenditure on health represents 8.7% of the total government budget. [8] Across the total population, 30% are covered by a public health service, public health insurance or social insurance, or other sickness funds [12] The total pharmaceutical expenditure per capita was SDG 72.3 (US$ 34.45). Pharmaceutical expenditure accounts for 2.2% of the GDP and makes up 36% of the total health expenditure. [13]

Sudan practices a "free market economy" and pay-per-fee system, whereby private dispensaries were set up in government hospitals and the public has to pay for medicines prescribed in these hospitals (except for the first 24 h emergency inpatients, blood transfusion services, renal dialysis and transplantation and many anticancer therapy). However, medicines prices are still under government control, in which the manufacturer, distributor and retailers have to set their prices under a "price regulation system" according to the Sudan Medicines and Poisons Act 1963, updated 2009. [14] In 2010, the NMPB issued a decree on medicine pricing [15] and according to its regulations; importers were asked to reduce prices between 15% and 80% of their registered cost and freight prices. So, whenever a new policy is introduced, it should meet an important objective of reducing prices and improving affordability without compromising availability. To investigate these issues, a study to measure medicines prices, their availability, affordability and price structure carried out in different sectors in Sudan to assess the impact of the new policy and any unintended consequences of the price intervention.

| Methods | |  |

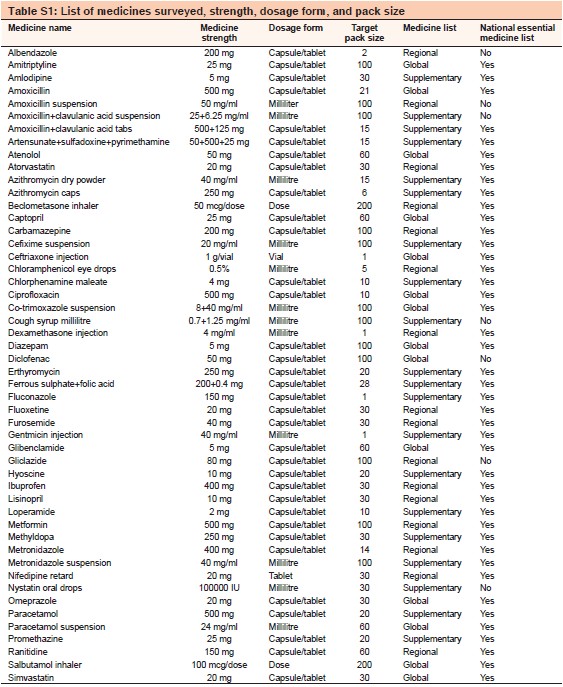

A field study to measure the availability, pricing, affordability and price components of a number of medicines was undertaken in the public and private sector in Sudan from March 2012 to April 2013 using a standardized methodology developed by the WHO and HAI. [3] The total number of medicines included in the survey was 50; 14 global list medicines, 16 regional list medicines and another 20 medicines chosen by the researchers to be included in the survey as supplementary medicines of local importance and frequently used in the country. All medicines included in the survey are included in Table S1.

Data was collected using a systemic sampling method in six geographical regions in Sudan, namely, Khartoum State, Gezeria State, Northern State, Red Sea State, North Darfur State, and White Nile State. Areas 2-6 are within 400 km (1 day travelling) from Khartoum State (Area 1). These regions are fairly representative of the whole country. In each area, one major city and four peripheral cities are chosen. In each area, the main governmental hospital in a major city and four other governmental hospitals or primary health-care centers in the peripheral city(ies) were sampled. The peripheral areas were no more than a 2-h drive from the major city. In each survey area, data was collected in the public sector, e.g. primary health-care centers and governmental hospitals, and the private sector, e.g. licensed pharmacies and licensed drug stores which were closest to each public medicines outlet. If there were a number of private outlets close to each public facility, one outlet was selected randomly from the lists of facilities obtained in advance. The distribution, the number of facilities sampled and the date of survey are listed in [Table 1]. An online map of Sudan containing the areas mentioned in [Table 1] is available on Wikipedia (http://www.upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia,commons/8/83/Map_of_Sudan_(New).JF). The public and private outlets/pharmacies were surveyed on both availabilities of the medicines and the price the patient pays. We also collected selling patient prices from 4 Khartoum state revolving drug fund (RDF) outlets and the main store of an NGO (charity) which supplies a group of pharmacies in Khartoum. Public procurement data were obtained from the Central Medical Store (CMS) 2009 tender - the body responsible for the medicines supply system of the Federal public health facilities-and the RDF 2011 tender- the body responsible for supplying Khartoum State hospitals and the State insurance system. For each medicine in the survey, data were collected for the originator brand (OB) - and the lowest-priced generic (LPG) equivalent - (generic product with the lowest price available at the facility).

A customize medicine price data collection form generated using the computerized workbook was used to record data from all outlets for the 50 medicines. Data on the price and availability of medicines in the public, private and other sectors (RDF and NGOs facilities) were obtained by collectors during visits to the medicines outlets. The pack size and price of that pack were only collected if it is physically in stock that day. The exception was in the Western region -Darfur area- as it was not stable at the time of data collection, so data collection forms were sent to the pharmacists to complete themselves and return to the investigators.

The data collectors were pharmacists and pharmacy students from the National University. They were trained how to fill the data collection form correctly. The data were entered in an electronic spread sheet ( Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Ramond Campus, Washington, USA) adopted specially by WHO/HAI, which automatically calculates median price ratios (MPRs), availability and affordability, etc., Data quality assurance done for accuracy include; checking of the data collection forms at the end of each day of data collection, double entry of data into the WHO/HAI workbooks, visual inspection of the data once entered by the survey manager and review of the data by HAI. Sudanese prices were compared to an international reference price (IRP), taken from the 2010 International Drug Price Indicator Guide produced by Management Sciences for Health. These are the medians of recent bulk procurement or tender prices offered by profit and nonprofit suppliers to developing countries for multisource products. Dividing the local unit price by the IRP provides a price ratio expressed as a MPR and it indicates how many times more expensive or cheaper the medicine is than the reference price e.g. an MPR of 2 would means that the Sudanese medicine price is twice that of IRP. The MPR was used as the summary measure. This facilitates national and international comparisons of medicines prices. Normally, an MPR of 1 or less is taken as efficient procurement in the public sector, while below 3 is considered acceptable for the private sector. [16] The Workbook calculated the MPR for each medicine type in each sector only if the medicine was available in at least four facilities.

The affordability of certain standard treatments to low wage earners was assessed by comparing the cost of treatment to the daily wage of the lowest paid unskilled government worker. The values obtained provide a measure of affordability. It was determined that the lowest paid workers receive around SDG 350/month or SDG 12/day ($ 3.20).

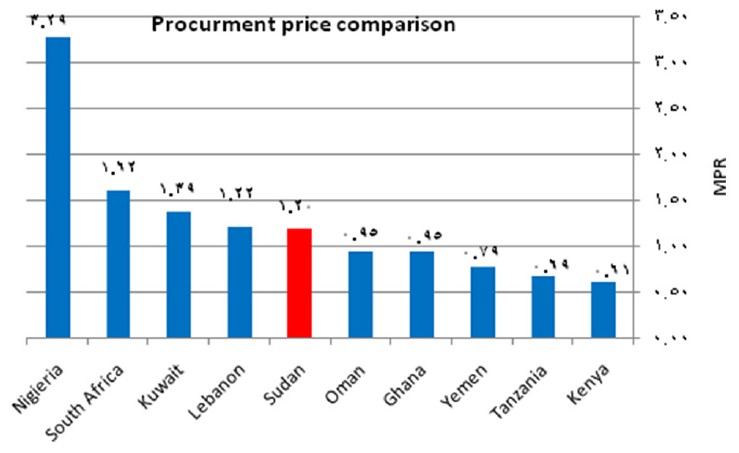

The manufacturer's selling price (MSP), taxes, mark-ups and other components contributing to the final retail prices of selected medicines were determined for a few imported and locally produced medicines in the public, private, CMS and RDF sectors to assess price structure. The WHO-HAI methodology was followed to collect data on the different stages in distribution chain. [17] Stage 0 of the component cost is (MSP). Stage 1 includes stage 0 and insurance and freight. Stage 2 includes customs charges, port charges and quarantine charges after the arrival of medicines to the country. It is also includes banking fees, and transport charges. Stage 4 is retailers' mark-ups. Stage 5 is composed of value added tax (VAT). As there is no VAT on medicines in Sudan, data for stage 5 could not be collected.

Comparisons of our 2012 results with a pervious study conducted in 2005 were determined for medicine prices, availability and affordability in different sectors surveyed.

| Results | |  |

Medicine prices

Based on median MPR, the CMS was procuring LPGs at 1.2 times their IRP, while they were selling generics at 2.34 times the IRP. The RDF was procuring LPGs at 1.55 times IRP, while they selling generics at 5.13 times the IRP. Both, the federal and state government procurement agencies are purchasing efficiently when buying generics but they sell generic medicines at higher prices and mark-ups over the procurement tender prices by (95% for CMS and 231% for RDF). For OBs only one medicine was procured by CMS and RDF. For CMS it was Salbutamol inhaler with a MPR = 1.88, while for the RDF Carbamazepine was the only OB procured and was found to be 16.55 times the IRP IRF. Comparing 2012 RDF procurement sector for LPGs median MPR with 2005, we found that the purchasing efficiency of RDF procurement sector in 2005 was better than 2012 as there is increase in mean MPRs in 2012 by 198% (from 0.52 in 2005 to 1.55 in 2012).

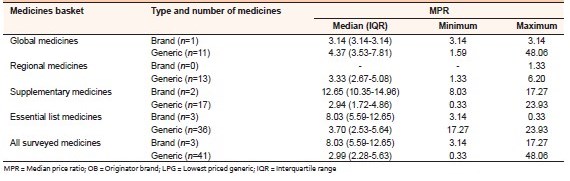

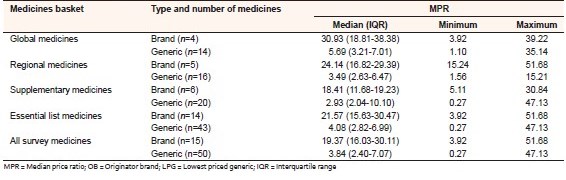

In public pharmacies the median MPR for LPG medicines was 2.99 and 8.03 for OBs. In private retail pharmacies the median MPR is 3.84 for LPG and 19.37 for OBs. [Table 2] and [Table 3] summarizes median MPR's for the different baskets of medicines for both OB and LPG in public and private sector outlets.

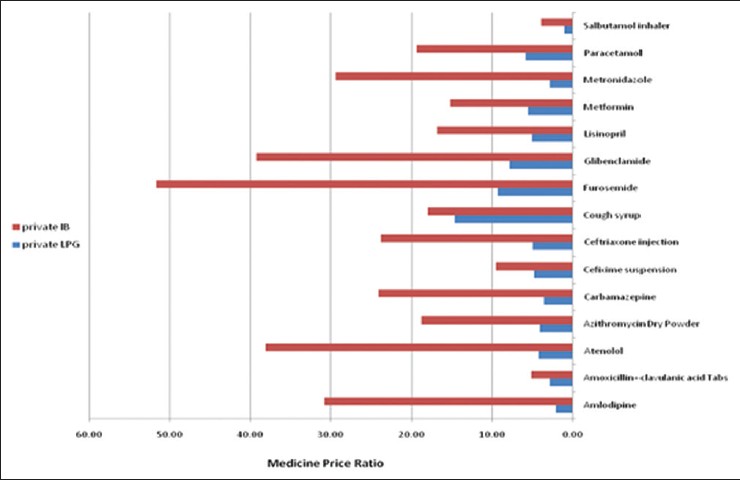

Region-wise comparison in public sector shows that Khartoum State had the highest median MPR for LPGs (3.96), while they were lowest in the Northern and Southern States (2.82 and 2.68 respectively). In private sector a lower MPR was shown in Khartoum and Northern State (3.6 and 3.02 respectively), while it was higher for Southern, Central and Eastern States (4.36, 5.93 and 8.3 respectively). 15 matched pairs of medicines were found for comparison between the OB and the LPG equivalent in the private sector. The median brand premium was 4.04 (meaning that the originator price was > 4 times the generic brand on average). The MPR for OBs compared with LPG medicines is shown in [Figure 1], and indicate that OB was more expensive than LPG equivalents for the all 15 medicines. By examining and comparing the MPR in public and private sectors for some selected medicines [Figure 2], an impression as there are number of products apparently high compared to what prices are available for generics on the global market could be achieved.

Comparing our study price results with a pervious study conducted 2005 we found there was increase in MPR of OB medicines in private sector by 6.4% (from 18.2 in 2005 to 19.37 in 2012), while there was lowering in MPR for low-price generic in private sector by 27.6% (from 5.3 in 2005 to 3.84 in 2012). There was lowering in MPR of low-price generic in public outlets by 37.5% (from 4.78 in 2005 to 2.99 in 2012). | Figure 1: Medicine price ratio in private sector for selected originator brands, and lowest priced generics medicines

Click here to view |

| Figure 2: Comparison between originator brand and lowest priced generic in private and public sectors for selected medicines

Click here to view |

| Table 2: MPR's for OB and LPG in public sector for different medicine baskets

Click here to view |

| Table 3: MPR's comparison of OB and LPG at private sector for different medicine baskets

Click here to view |

The NGO median MPR was higher than other sectors (18.42 for OB and 5.01 for LPG) which may indicate that they purchased from private wholesalers rather than have their own procurement or do they just charge a very high mark-up on medicines, however; we are not sure about that as this data was based on only 1 outlet.

[Table 4] shows the comparison of median MPR for medicines found in both public and private sectors. Overall, OB medicines were found to be 19.1% lower priced in the public sector than the private sector but this was based on only 3 medicines. LPG medicines were found to be lower priced in the public than private sector by14.6% (across 41 medicines).

Availability

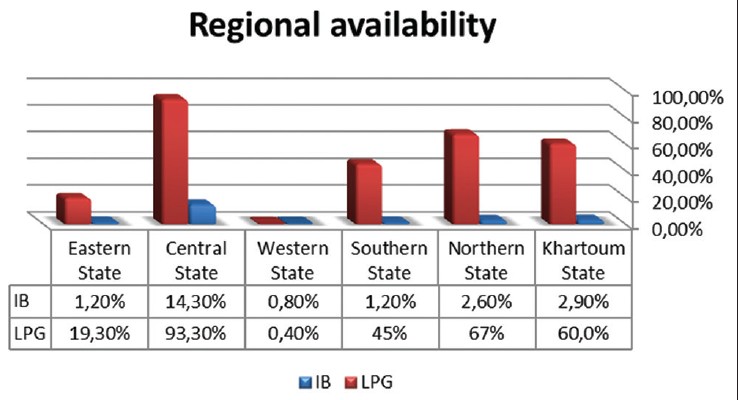

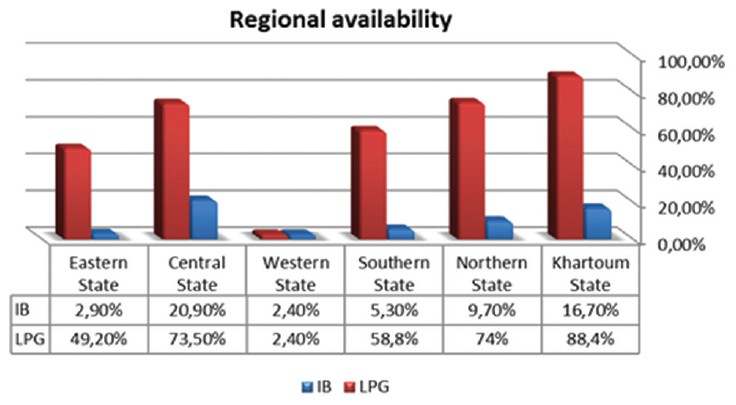

In the public and private outlets surveyed, generic medicines were the predominant products. The mean percentage availability of all surveyed medicines in the public sector was low at 1.8% for OB medicines and 39.5% for LPG. There was a big variation in median availability among the 6 regions surveyed. The lowest availability was seen in the Western State (a conflict area) at 0.8% for OBs and 0.4% for LPGs.

The availability in private outlets surveyed was higher than in the public sector for both products types (originators or generic medicines) with generic medicines having the greater availability (but still sub-optimal at < 60%). The mean percentage availability of all surveyed medicines in the private sector was 9.3% for OB medicines and 56.6% for generics (LPG). Mean availability varied across the 6 regions surveyed. The lowest availability was also in Western State 2.4% for OB and 2.4% for LPG [Figure 3]. | Figure 3: Cross regional availability (%) for originator brands and lowest priced generics in private sector

Click here to view |

Comparing our study availability results with a pervious study conducted 2005 for the same medicines surveyed in both years that had the same strength and dosage form, we found there was a reduction in availability of low-price generic in private outlets by 18.9% in public outlets (from 59.1% in 2005 to 40.2% in 2012), and by 26.8% (from 84.5% in 2005 to 57.8% in 2012).

Affordability

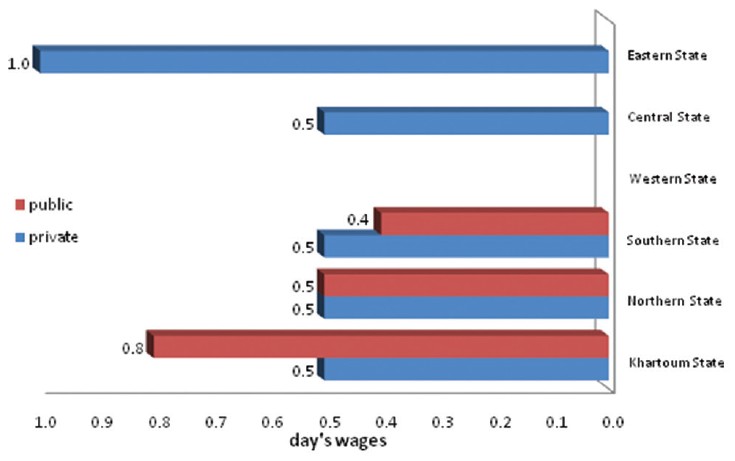

The affordability of LPGs in the public sector was good for half of conditions, with standard treatment costing a days' wage or less for 53.3% of treatments. In the private sector, the affordability of lowest price generics was similar to the public sector. 1-month treatment of OB Amlopidipine for hypertension required about 9.0 days' wages when purchased from private pharmacies. The generic versions of Amlopidipine, on the other hand, cost < 1 (0.7) a days' wages in both public and private sectors. The government worker would have to work 2.5 days to pay for 1-month of treatment with OB Glibenclamide for diabetes when purchased from private pharmacies, for LPG Glibenclamide he has to pay about half-a day's salary to buy the medicines from public and private sectors. [Figure 4] illustrates the treatment affordability in different regions in country for LPG Glibenclamide 5 mg.

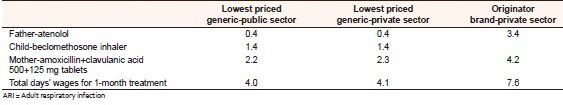

The burden is especially greater for a family needing treatment for several conditions at the same time. An example is provided below of a family where the father has hypertension and the child has asthma and mother has adult respiratory infection. If the family is earning the equivalent of the lowest-paid government worker's salary, total treatment costs are 4.0 days' wages in the public sector and 4.1 days' wages in the private sector if the lowest price generics are purchased. If OBs are purchased, treatment costs about 7 days' wages in the private sector excluding an inhaler [Table 5]. | Figure 4: Affordability of lowest priced generic Glibenclamide by region, in private and public sectors

Click here to view |

| Table 5: Affordability of treatment for a family with hypertension, asthma and ARI: Number of days' wages of the lowest paid government worker needed to purchase standard treatments

Click here to view |

Price components

In procurement sectors mark-ups added on tender awarded prices to get the selling price averaged 70% and 123% for CMS and RDF respectively. The average retail prices were within the official profit for CMS public pharmacies (20%) while it was double the official profit for RDF pharmacy outlets (41%).

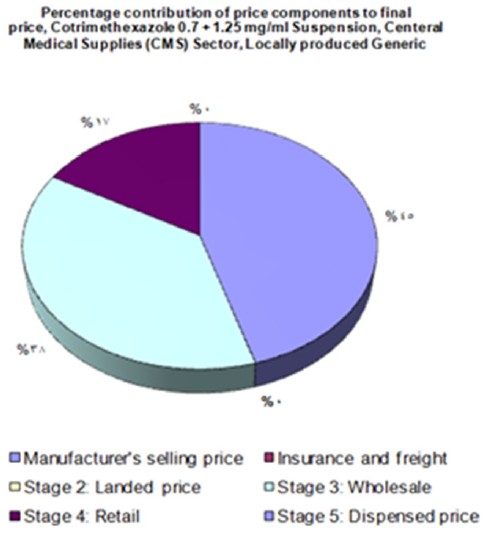

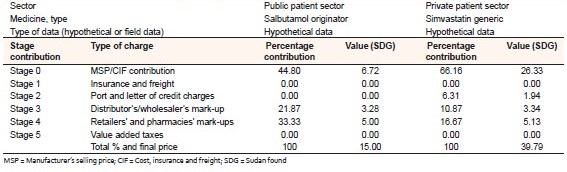

Competitive procurement prices from CMS and RDF do not appear to be passed on to patients. The percentage of mark-ups and contribution were analyzed as per WHO/HAI methodology for some medicines procured through CMS and RDF and an examples were shown in [Figure 5] and [Figure 6]. | Figure 5: Contribution of different stages to patient prices when procured via central medical store

Click here to view |

| Table 6: Contribution % to final patient price in the public and private sectors

Click here to view |

| Figure 6: Contribution of different stages to patient prices when procured via revolving drug fund

Click here to view |

We obtained the price structure of OB and LPG imported medicines to understand the pricing components in the public and private sectors respectively and to determine the main price components which contributed in medicine prices in Sudan. Higher contribution to final patient price was found of MSP/cost, insurance and freight 48.8% and 66.16% and followed by retailer's mark-ups 33.3% and 16.67% in public and private sectors respectively, as shown in [Table 6].

Medicines prices in Sudan from international perspectives

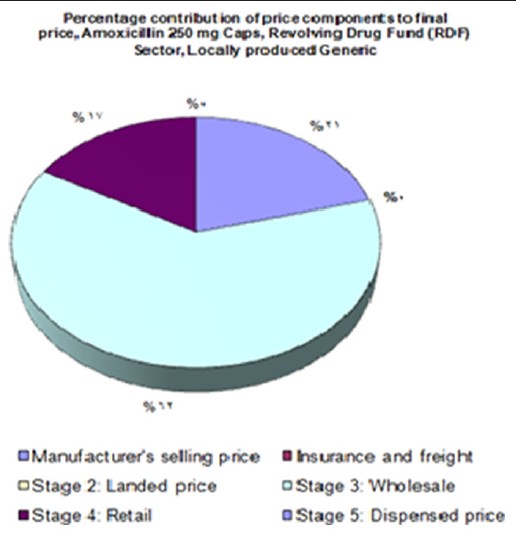

Price, availability and affordability comparisons of the medicines have been made between Sudan and of a group of 10 countries who have conducted surveys using the WHO/HAI methodology and shared the same characteristics in terms of pharmaceutical regulatory, economic indicator and/or development. Results for procurement prices of LPG showed that government procurement prices in Sudan (2012) were approximately between the nine countries. Overall, Sudan's public sector appears to be purchasing medicines less efficiently than 5 countries, and more efficiently than the other 4 countries [Figure 7]. | Figure 7: Comparison of Sudan procurement median price ratio to 9 countries for lowest priced generic

Click here to view |

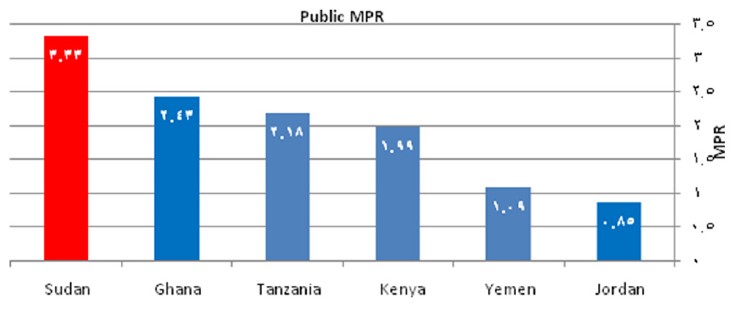

Results for public MPR comparison for LPG could be made for 5 out of 10 countries selected and were showed that public prices in Sudan (2012) are the highest among five countries as shown in [Figure 8]. | Figure 8: Comparison of Sudan public median price ratio to 5 countries for lowest priced generic

Click here to view |

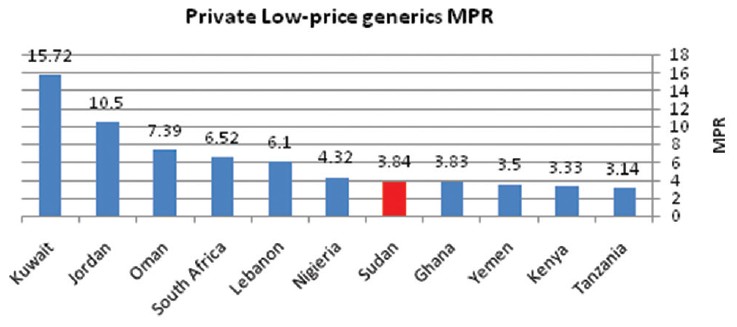

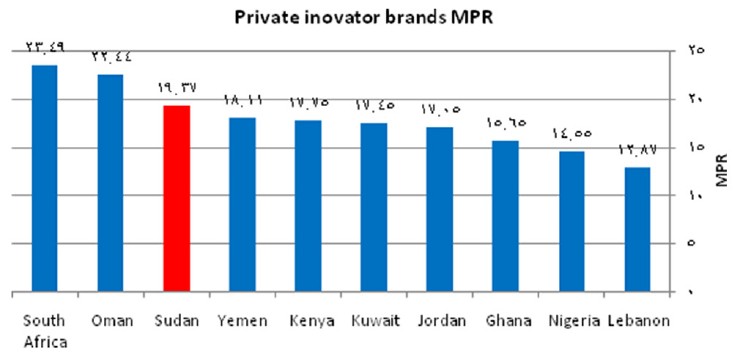

The private MPR for LPG in Sudan (3.84) was modest that it is lower than six of the selected countries for comparison but higher than four of them, while for private OB it is higher than MPRs of 7 countries and lower than 2 countries as shown in [Figure 9] and [Figure 10]. | Figure 9: Comparison of Sudan private median price ratio to 10 countries for lowest priced generic

Click here to view |

| Figure 10: Comparison of Sudan private median price ratio to 9 countries for originator brands

Click here to view |

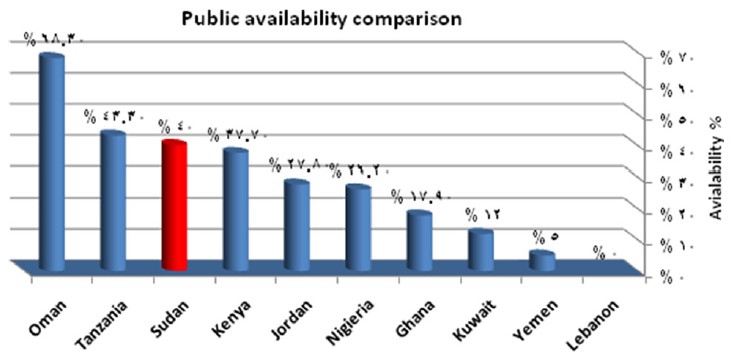

The OB medicines availability in public sector was poorest in Sudan (4%) compared to Kuwait (12%), Oman (13%) and Nigeria (21%). The availability of medicines in public sector for LPG medicines was less in Sudan (40%) than 2 countries Oman (68.3%) and Tanzania (43.3%) but it is better than 7 of countries compared as shown in [Figure 11]. | Figure 11: Availability comparison of lowest priced generic medicines in public sector between Sudan and 9 countries

Click here to view |

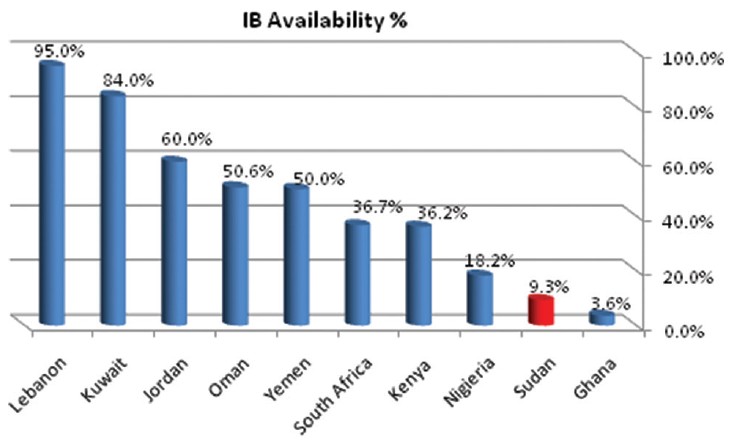

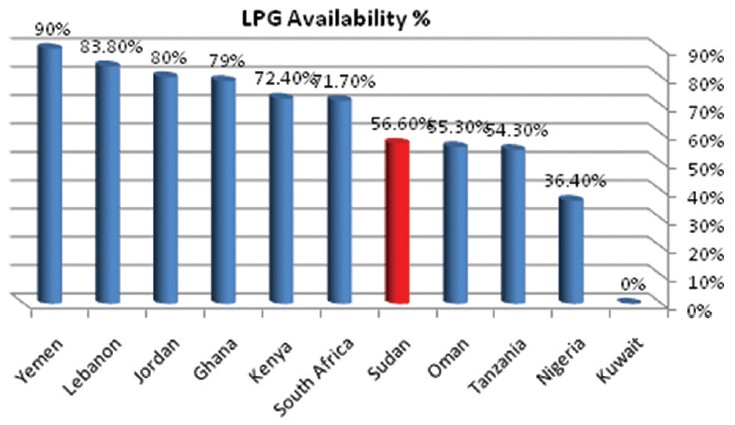

The OB medicines availability in private sector was least in Sudan (9.3%) compared to other 9 countries as shown in [Figure 12]. The availability of medicines in private sector for LPG medicines was better in Sudan (56.6%) than 4 countries Oman (55.3%), Tanzania (54.3%), Nigeria (36.4%) and Kuwait (0%) but it is <6 of countries compared as shown in [Figure 13]. | Figure 12: Availability comparison of originator brand medicines in private sector between Sudan and 9 countries

Click here to view |

| Figure 13: Availability comparison of lowest priced generic medicines in private sector between Sudan and 9 countries

Click here to view |

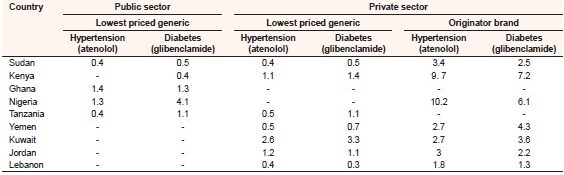

The survey found marked differences in affordability between counties for medicines within a therapeutic category. [Table 7] demonstrate these differences for two medicines used in treatment of hypertension (Atenolol 50 mg) and diabetic (Glibenclamide 5 mg) for 1-month across 4 African countries in the public sector for LPGs and 2 African and 4 Mediterranean countries in private sectors for both OBs and LPGs. | Table 7: Public and private sector affordability comparison between Sudan and some selected countries

Click here to view |

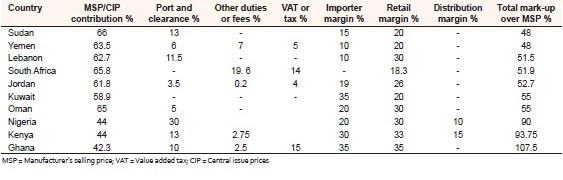

For international comparisons of price component, the private sector is the most transparent and the charges are nondiscriminatory, and the same percentage is charged for all medicines. This could enable us to make international comparisons between Sudan and other countries components in the private sector [Table 8]. | Table 8: International comparison of price component summary for medicines in private sectors

Click here to view |

From the table below, Sudan was the least of mark-up over MSP and only comparable to Yemen, but it was the highest in MSP/central issue prices contribution among the compared countries.

| Discussion | |  |

The survey results show that patients are paying significantly more to purchase originator products than lowest price generics in all sectors surveyed. In Sudan public procurement of medicines is generally efficient in achieving reasonable prices but the patient price in the public sector was about 2 times greater than the public procurement price (Tender price), indicating substantial add-on costs in public distribution system for those medicines the government is purchasing. This may also be explained by the fact that the public sectors facilities belonging to CMS and RDF tend to base their prices more according to their competition (private retail pharmacies) than a simple mark-up on procurement price. They included mark-ups perhaps to cover their warehousing and distribution cost and to ensure that funds are not recapitalized and to ensure provision for depreciation due to inflation.

In the public sector, the MPR for lowest price generic medicines was 2.99 times their IRP, while for OB medicines it was 8.03 times their IRP (but only 3 OBs were procured). In the private sector, the MPR of lowest price generic medicines was 3.84 times their IRP, while for OB medicines was 19.37 times their IRP. Though it is not possible to define the "right" MPR in the private sector, we consider MPRs of < 4 as reasonable and acceptable due to high inflation rate and deficiency of foreign currency.

Prices of OBs are considerably higher than LPG equivalents in all sectors. As is expected, generic medicines are more affordable than the OB equivalents. The generic versions were more readily available in all the sectors than the OBs. This shows an acceptance of generic medicines in the country although there is no legislation requiring generic prescribing or substitution.

In a parallel study conducted by the GDP 2012-2013, found that LPGs median MPR in public procurement was 1.87 for CMS and 2.7 for RDF. LPGs median MPR for Public sector patient was 2.98 and private sector was 2.9. For OBs median MPR in public procurement was 1.88 for RDF. OBs median MPR in Public sector patient was 2. 67 and for private sector was 4.24. [18]

The survey showed low availability of the basket of medicines surveyed in both the public and private sectors; this is inconsistent with the results of a previous survey carried out in 2005 which shows availability of medicines in the public sector and private sectors were better than 2012. GDP study results show that LPGs availability was found to be 68.1% in the public patient sector and 83.9% in private sector and this difference between our results and GDP results may be accounted to the fact that GDP study did not include the (Darfur State-the real western region) in their study as it is a conflict area and considered (North Kordfan) as the western region and this is could not make their study actually representative for whole Sudan at the time of study. Also it may be because of the different baskets of medicines surveyed.

However; the intervention carried out by NMPB to reduce the prices in Sudan may have unintended had a negative effects on the availability as a result of discouraging the principals and importers in stocking medicines and make many companies less likely to invest in medicines and redirect their interest to other types of importation like paramedical, consumables and food supplements which is their pricing system uncontrolled like medicines. Other reasons may be the inflation happened during our survey period due to secession of South Sudan which contained over 80% of Sudan's oilfields, the economic forecast for Sudan in 2011 and beyond is uncertain owing mainly to loss of oil revenue by 75% from Sudan's budget which led to depletion of foreign exchange reserves and affecting the availability of foreign currency to import medicines from outside especially if we know that the imported drug constitute about 70% of whole registered medicines in Sudan. However, enforcing low prices could have a perverse effect on availability by providing a disincentive for stocking these products. In-depth studies are needed to determine factors affecting availability of medicines.

Affordability was also calculated in terms of the government worker who earns < US$ 3.20/day. Few Sudanese are employees earning this minimum wage and indeed majority of Sudanese earn below US$ 3.20/day. While affordability was measured in terms of only a single medicine, it is important to note that studies show that the average number of medicines per prescription in Sudan is around 2 in public hospitals and primary care centers and more than that in private clinics. [19],[20] Therefore, most conditions are treated with more medicines than calculated by this survey; as the real cost would be an aggregate of the cost of the individual medicines including the equipment used to deliver the medicines. The calculated medicine cost represents a fraction of what would be paid by the family at any given time other costs were not included such as doctor's fees and laboratory investigations, etc., This study shows that the affordability of medicines is greatly dependent on the selection of medicine between the generic version and the OBs with the latter being less affordable. Choice of sector was also important as there was decrease in cost of medicines in a descending order from the private sector, through the public health sector. Studies show that at least 65% of the population uses private pharmacies for their health needs, [21] may be because of the impression that the accessibility and availability of medicines in private pharmacies is better than the governmental public pharmacies. Even so, medicines are clearly unaffordable to most people especially the Sudanese poor populations who also spend > 90% of their income on food. Irrational selection of medicines can have a great impact on affordability.

Mark-ups represent a large proportion of the price the patient pays in Sudan. Mark-ups vary from medicine to medicine and from sector to sector. Analysis of costing documents shows that wholesale mark-ups are more variable than retail mark-ups among different sectors. The wholesale mark-ups in the public sector ranged from 125% in CMS to 240% in RDF, and in private sector mark-ups of wholesaler is fixed at 15% (although actual mark-ups were not measured), while the retail-up in the public sector ranged from 11% in CMS to 50% in RDF, and in private sector it is 20% (although this was not measured in the field). It seems that the public sector takes advantage of the low price of generics from tender prices to increase mark-ups. It supposed to be reflected positively on the availability of medicines in these sectors, by purchasing more drugs. Thus, interventions into procurement costing system may make a real difference in the cost and availability of medicines in public sector in Sudan.

Comparing prices in Sudan with other countries has confirmed the prices for generics in Sudan are modest in procurement and private sectors compared to other sectors while it is the highest among the public patient sector which may confirm that the public patient sector in Sudan is not a pure public sector but it is a private sector installed into a public premises. The MPR of the OB prices in private sector are higher than in three Arab countries with much higher GDP per capita namely: Jordan, Lebanon and Kuwait.

Comparing our study price results with a pervious study conducted 2005 we found there was increase in MPR of OB medicines in private sector by 6.4% (from 18.2 in 2005 to 19.37 in 2012), while there was lowering in MPR for low-price generic in private sector by 27.6% (from 5.3 in 2005 to 3.84 in 2012). There was lowering in MPR of low-price generic in public outlets by 37.5% (from 4.78 in 2005 to 2.99 in 2012). Concerning availability there was a reduction in availability of low-price generic in private outlets by 26.8% (from 84.5% in 2005 to 57.8% in 2012), and by 18.9% in public outlets (from 59.1% in 2005 to 40.2% in 2012).

There are many limitations to our study, firstly; study results may be limited by the fact that data are inherently subject to outside influences such as market fluctuations and long time schedule of the study which was due mainly to some logistic problems encountered. Secondly; the availability is determined for the list of survey medicines, and therefore does not account for the availability of all registered medicines or alternate strengths or dosage forms, or of therapeutic alternatives. Thirdly; price components were reviewed from different sector documents and not taken from the field so we are unsure if mark-ups adhered to costing approved by the NMPB. Finally; the study done in 2005 which we compared with was restricted to Khartoum State, while our results are representing the whole country. The data may be more comprehensive if we make national to national comparison rather than state to national comparison.

| Conclusions | |  |

In Sudan, the availability of the surveyed medicines was extremely low in all sectors as originator and 60% or less as generics (only 39.5% in the public sector) Generic medicines have been accepted in the country as they are more available than OBs in all sectors. To improve access to medicines, patients should pay procurement prices in the public sector plus a nominal distribution cost. High costs in procurement public distribution system added substantially to the price of generic medicines patients pay at public health facilities. The public sector should not work as private wholesalers and competitors to importing private companies. Public pharmacies in hospitals should not be act as private retail pharmacies financed by medicine sales revenue but should be financed by the government.

In both the private and public sectors, considerable price differences were seen between OBs and generics. In general, OBs were 4 times more expensive than the lowest priced. Medicines are often unaffordable for ordinary citizens. The treatment of a chronic disease such as hypertension, where prices are high, availability low and affordability poor, warrants urgent attention. Service providers must be encouraged to dispense cheaper generics whenever possible to improve affordability of medicines as dispensers need incentives to dispense LPGs, so we have to consider introducing regressive mark-ups rather than fixed percentage mark-ups.

The impact of policy changes made should be measured by establishing a monitoring system to monitor not only regularly the prices, but also the availability and affordability of medicines. The preliminary results of this study suggest that the price reduction policy need to be reconsidered to make medicines more available. Although further investigation is required to obtain a more in-depth understanding of the causes and consequences of medicine pricing and availability, the results of this survey provide broad directions for future research and action.

This report is an outcome of a systematic study employing the WHO/HAI methodology and is an attempt to address the pricing problems. We strongly believe that the findings and suggestions given herein would give current and close picture about the medicines situation in Sudan, and would be helpful and useful for devising an effective pricing policy. The results highlight priority areas for action for the ministry of health and others in improving access to affordable medicines. Broad debate and dialogue are now needed to identify how best different players can contribute to the prospect of enhancing accessibility and affordability to essential medicines.

| References | |  |

| 1. | World Health Organization. Economic aspects of drug use (Pharmacoeconomy). In: Introduction to Drug Utilization Research. Oslo, Norway: World Health Organization Publications; 2003. p. 26.  |

| 2. | Quick JD, Rankin JR, Laing RO, O'connor RW, Hogerzeil HV. editors. Managing Drug Supply. 2 nd ed. West Hartford (Connecticut): Kumarian Press; 1997. p. 7-9.  |

| 3. | World Health Organization. Health Action International. Measuring Medicine Pricing, Availability, Affordability and Prices Components. 2 nd ed. 2008. Available from: http://www.haiweb.org/medicineprices/manual/medicineprices.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Jun].  |

| 4. | "Sudan- Population". Library of Congress Country Studies. Available from: ???. [Last retrieved on 2013 May 31].  |

| 5. | Abdalla T. Hummad (FMOH). Sudan Pharmaceuticals Country Profile; 2010.  |

| 6. | Annual Health Statistical Report. Khartoum: National Ministry of Health; National Health Information Centre; 2009.  |

| 7. | World Health Statistics. The Global Health Observatory. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/ghodata/. [Last accessed on 2010 May 12].  |

| 8. | General Directorate of Pharmacy. The Pharmaceutical Stastical Report; 2012.  |

| 9. | Annual Report of the Regional Director. Cairo: World Health Organization; Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO); 2008. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/rd/annualreports/2008/pdf/indicators_healthstatus.pdf. [Last accesssed on 2010 Jun 08].  |

| 10. | Federal Ministry of Health; Annual Pharmaceutical Statistical Report, 2007.  |

| 11. | Sudan census. Khartoum, Central Bureau of Statistics, 2008. Available from: http://www.cbs.gov.sd/Tiedadat/Tiedadat%205 th %20E.htm. [Last accessed on 2010 Jun 08].  |

| 12. | FIP Global Pharmacy Workforce Report. The Hague, Federation. Internationale Pharmaceutique (FIP); 2009. Available from: http://www.fip.nl/files/fip/2009%20GPWR%20Part%205.5%20Sudan.pdf. [Last accessed on 2010 Jun 08].  |

| 13. | Annual Pharmaceutical Statistical Report. Sudan: MOH; 2006-2007.  |

| 14. | Medicines and Poisons Act, 2009. Available from: http://www.nmpb.gov.sd/Regulations/The%20 medicines%20and%20poisns%20act%202009.pdf. [Last accessed on 2010 Jun 08].  |

| 15. | Registered Pharmaceuticals Pricing Decree, 2010. Available from: http://www.nmpb.gpv.sd/regulations/the20%medicines20%pricing20%decree20%2010.pdf. [Last accessed on 2013 Jun].  |

| 16. | Gelders S, Ewen M, Noguchi N, Laing R. Price, availability and affordability: An international comparisons of chronic disease medicines. World Health Organization and Health Action International, Cairo, 2006. Available from: http://www.mednet3.who.int/medprices/chronic.pdf . [Last accessed on 2013 Jun].  |

| 17. | World Health Organization. Health Action International Price Component Handbook. Geneva: WHO; 2008.  |

| 18. | Health Action International Global Database (Sudan February 2013) Available from: http://www.haiweb.org/MedPriceDatabase/. [Last accessed on 2013 Jun].  |

| 19. | Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: A secondary analysis. Lancet 2009 17;373:240-9.  |

| 20. | Awad AI, Himad HA. Drug-use practices in teaching hospitals of Khartoum State, Sudan. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:1087-93.  |

| 21. | Abelmoneim IA, El-Tayeb IB, Omer ZB. Investigation of drug use in health centers in Khartoum State. Sudan Med J 1999;37:21-6.  |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3], [Figure 4], [Figure 5], [Figure 6], [Figure 7], [Figure 8], [Figure 9], [Figure 10], [Figure 11], [Figure 12], [Figure 13]

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3], [Table 4], [Table 5], [Table 6], [Table 7], [Table 8]

|