Introduction

‘Spare us, for once please not about the war – we hear the sympathetic reader tell us. This request can be granted, for the literature on the world war is overwhelming’. Thus began the column on economics in the September 1915 issue of the monthly Dutch Christian opinion magazine Stemmen des Tijds.1 With this statement the author aptly pointed to the (understandable) obsession of many with the subject of the Great War. This is hardly surprising, for it had sparked a crisis in the neutral Netherlands at many levels, not least of which the religious.2 This led to what the orthodox theologian Herman Bavinck (1854–1921) the year before had referred to as ‘the problem of the war’:fg001

This war presents us with a great embarrassment, and we do not know how to give it a place in our reasonable, moral, Christian worldview. Who can show us what the cause of this war is, why it began and what end it will serve? From whatever side one views it, no light can be seen anywhere, as it is shrouded in darkness. It appears that it no longer has a place in our lives, and falls outside the framework of this age.3

This problem was not for the Dutch alone to deal with, of course. Throughout Europe, churchmen struggled with it, most notably in the warring nations. In Germany and England – the nations generally most important in defining Dutch debate in this period – the powerful state churches were immediately mobilized to bless the war effort of the home nation and condemn that of its foes.4 In both countries, churches tended to portray the war as a result of the many ills that characterized modern culture and society; materialism, militarism and secularization among them. However, they also attempted to use the war as a means of countering these same evils and bringing people back to the church.5

Owing to a virtual absence of studies on Dutch wartime theology, it is much less clear how men of the Church in the Netherlands dealt with the ‘embarrassment’ identified by Bavinck. In the years since Hans Krabbendam pointed to this problem (in 2002), the situation has improved, but only a little.6 In this paper, I endeavour to shed more light on this issue by studying various writings on the war by Dutch theologians. My goal is twofold. First, I want to look at how the question of the war was treated – whether it was just and what had caused it. Second, I will look at how the war figured in the larger Christian worldview, in particular how it related to the specific problems posed by modern times.

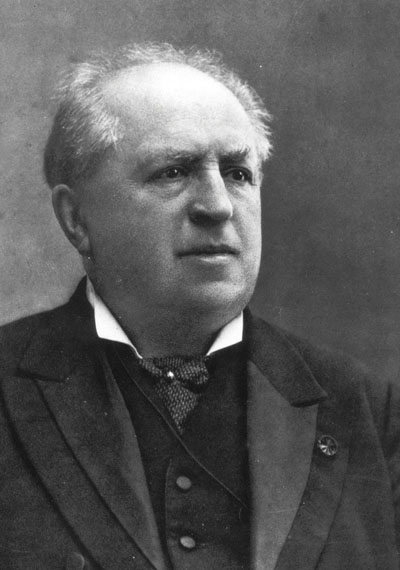

I will draw rather heavily on the studies by Enne Koops on war sermons, and by Dirk van Keulen on a number of war-related essays written by Bavinck between 1914 and 1919.7 I will follow them in restricting myself largely to the Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland (Reformed Churches in the Netherlands, hereafter GKN), a ‘neo-Calvinist’ church denomination that had its origins in the nineteenth century, when this branch was splitt off from the larger Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church, hereafter NHK).8 To this end, I will discuss the writings of Bavinck and Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920), whose centrality in formulating and maintaining the neo-Calvinist view of the world (up to and including the war) can hardly be overstated.9 A number of their books, articles, and lectures will provide the body of much of what follows. According to Van Keulen, Bavinck was the only theologian of the GKN to reflect on the problem of the war during the First World War. I will dispute this by discussing the wartime editions of Stemmen des Tijds, along with a number of other theological writings on the war.10 It turns out that all aspects of the war were discussed and debated extensively in theological venues – almost ad nauseam, as the quote heading this paper illustrates.

Modern culture presented people with science, technology, increased well-being and wealth, but also brought along changes in religiosity and morality that were not universally judged to be positive (to put it mildly). It was a task for many theologians to strike a balance between those sides of modernity.11 The war brought the darker aspects of the age acutely to the fore, and many churchmen felt pressed to try and grasp it in terms of their belief systems.12 I will argue that theologians of the GKN largely failed to do so, due to the orthodox position on war that they were prone to defend. Moreover, this failure to provide a much-needed answer seems to have been one of the reasons for the rise of alternative ideologies such as spiritualism, and the necessity for a reformulation of orthodoxy after the war. But it is to the late nineteenth century neo-Calvinist approach to modern culture and society that I turn first, focusing on the role of Kuyper and Bavinck in formulating and implementing it.

Modernity, Orthodoxy and Neo-Calvinism

Abraham Kuyper was born in 1837 in the town of Maassluis, where his father preached a mild, sober Protestantism as a clergyman of the Reformed Church. During his university years and early career as a clergyman, the young Kuyper gradually became disillusioned with his father’s faith and rejected this approach to Christianity in favour of a much stricter Calvinism. The modern protestant faith as preached in the NHK, with its liberal approach to science and the Bible and its reconciliatory stance towards modern social developments, was much too similar to godless philosophies for Kuyper. Johannes Henricus Scholten (1811–1885), for instance, had become one of the founders of the ‘modern’ school in Dutch theology by incorporating the views of the German philosopher Georg W.F. Hegel (1770–1831) on spiritual progress into Protestant theology, denying the significance of miracles and interpreting revelation as an ongoing process rather than a singular event recorded in the Bible. The Reformed Church, Kuyper felt, was weak, and incapable of dealing with the social and religious problems of the time.13

Calvinism gave Kuyper a way of approaching these problems, and his long life can be seen as an integrated attempt at realizing his vision of a proper, Christian society. The NHK was in moral decline, as was much of the rest of society, which ended up on the wrong side of Kuyper’s famous ‘antithesis’ between those who live in Christ and those who live without him.14 The goal was a pure theology, a pure Christian community, fully cognizant of the possibilities of modern society (e.g. science, democracy), but unspoiled by its ills (e.g. pantheism, secularism).15fg002

Kuyper was remarkably effective in organizing his neo-Calvinist society. In 1872, he became editor of a daily newspaper, De Standaard, which he could (and would) use to give his opinion of basically anything, most notably through his famous ‘Driestarren’, short columns (with three stars in the head) of which he would produce almost 17,000 between 1872 and 1920.16 In 1876, he became leader of the new orthodox Calvinist Anti Revolutionaire Partij (ARP), through which he would create a strong voice for anti-liberal politics.17 In 1880, the Free University (Vrije Universiteit, in short: VU) was founded, which soon began producing neo-Calvinist clergy and theologians. All this culminated in the ‘Doleantie’ of 1885–1886, in which a fair portion of the Reformed Church congregations split off. A few years later, after a fusion with another, earlier Reformed offshoot, the Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland (GKN) were formed.18

Bavinck was less fond of operating in the spotlight, and as a theologian he was much more nuanced in his views and less confrontational in style than Kuyper. Nonetheless, he played no less an essential role for the GKN, and he figured prominently in defining the basic principles of the neo-Calvinist faith.19 Bavinck distinguished the most fundamental tenets of neo-Calvinism from the less fundamental ones, and argued for a degree of plasticity on the latter. This would smooth the communication between different denominations.20

The essence of this neo-Calvinist theology can be found in its attempt to strike a balance between modernity and orthodoxy, without doing harm to either. The anti-religious (and anti-authoritarian) ni Dieu, ni Maître of the French Revolution was rejected in favour of a life where the fundamental aspects of the Christian faith seeped into every crevice. These fundamentals – e.g. adherence to the authority of the Bible, revelation, and submission to Christ – should define everything including politics, social life, science, etc. Time and again Kuyper would warn against a fading of the boundaries between the religious and non-religious life, and the necessity of keeping that boundary in place.21

None of this would imply a denial of modernity, however, and both Kuyper and Bavinck happily incorporated modern science and scholarship into their views, only with a restored Christian foundation. The facts established by the natural sciences, for instance, had to be divorced from pagan ideologies (such as evolution and pantheism) and placed onto a Biblical foundation.22 This was a balancing act that led to a decent amount of criticism – the neo-Calvinists were accused of wanting to have their cake and eat it too. Modern theologians, such as C.B. Hylkema, argued that Kuyper and Bavinck basically practiced modern theology with an orthodox vocabulary.23 Bavinck in particular felt the need to defend the neo-Calvinist synthesis and distinguish it from both modern theology and everything else.24

This short (and grossly oversimplified) history of the GKN will serve as an introduction for what is to come. The world dominated by Kuyper and Bavinck was well organized and structured, both institutionally and in terms of ideas.25 The neo-Calvinists, despite a propensity for a certain degree of isolationism and their strong criticisms of basically everyone else in Dutch society, tended to have a positive view of the future. They did see the evil in modern developments, and a certain degree of cultural criticism was ever present, but they also observed a waning of materialist philosophy and a growth in international evangelization. One might then conclude that, despite the occasional exception, no one was expecting the war.26 But when it did come, and the problem of the war was posed by Bavinck and others, answers were provided quickly. But to the extent that answers could be provided, neo-Calvinist views on the First World War were a continuation of views on war, peace and society developed in the years before the conflict.

War as a Theological Problem

Can wars be just? This seems to be an essential question for any moral system, especially in wartime. Van Keulen expresses surprise, therefore, at his observation that theologians of the GKN seemed insufficiently occupied with it. He writes, ‘As far as I know, the only theologian of the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands who, during the First World War, has reflected explicitly on the fundamental question of whether war can be united with the Christian faith, is Herman Bavinck’.27 Kuyper also treated the question rather systematically, however, a fact that Van Keulen is aware of but dismisses due to Kuyper’s thinking about the war in terms of nineteenth century categories. This may well be the case, but it appears that the two men reached rather similar conclusions and, most importantly perhaps, that neither of them made significant changes to the neo-Calvinist answer to this question that had been formulated years before the war.

While the question of war and justice had kept believers (and non-believers alike) busy for many a century, it had been rather high on the agenda in the early years of the twentieth century due to the rise of such phenomena as the international peace-movement. Supporters of this movement (often but not always socialists) tended to see war as a barbaric activity that modern, civilized humanity had to outgrow.28 It was thus important for those who would not categorically reject war, to explain how it could (sometimes) be a good thing, or at least permissible, and thinkers of the GKN had little trouble formulating an answer.

One version of the ‘neo-Calvinist view of war’ can be found in a speech given before the lower house of parliament by Jhr. Alexander Frederik de Savornin Lohman (1837–1924), a politician and law professor who, despite many a conflict with Kuyper, remained loyal to the GKN and its neo-Calvinist ideology.29 De Savornin Lohman sets out to distinguish just from unjust wars by arguing that the anti-militarists confuse means and ends. Whether or not a war is just depends on the end it is supposed to serve – if used for the right purpose, it is in fact very similar to punishing a criminal. States do sometimes abuse their right to punish, but that does not make the act of punishing in itself evil or unjust. ‘In our circumstances war is after all the only, though also the last, means of safeguarding law and freedom’.30

In his 1914-essay in Stemmen des Tijds, Bavinck gives solid Biblical support to what is essentially the same position defended by de Savornin Lohman in 1900. In a broad sweep of the Old Testament, he points out that God explicitly sanctified numerous wars, which were fought for just causes. The New Testament too, he argued, does not forbid war but merely discourages it. Truth and Justice are, after all, more important than life and peace, and there are evils in this world we should never allow ourselves to live in peace with. Bavinck refers to the pacifist clergyman Martinus Beversluis (1856–1948) who had written of God and war as ‘an irreconcilable antithesis’.31 Bavinck replies that

whoever experiences such miseries can hardly reach any other conclusion than that war clashes with God’s will [...] Conversely, the justice, necessity and utility of war has found powerful supporters in men such as Hegel, Cousin and Spencer. [...] Christianity can be reconciled with neither sentiment.32

In a 1919 essay, Bavinck goes on to list a number of rules for a just war – it must be fought by a just government, for a just cause, with a pure intention and by just means – and he places himself in the tradition of Ambrosius, Agustine, Aquinas, Calvin, etc.33

Kuyper, too, rejects any form of pacifism, and does so in much stronger terms than Bavinck, even though the arguments are again very similar. Whereas Bavinck hastens to point out that his view of the New Testament as it relates to the question of war and justice is rather controversial, Kuyper simply states that the Bible forbids pacifism. World peace will only be established after the Second Coming of Christ, the ‘Great Catastrophe’. Until that event, wars are simply a part of our human condition.34

It is not hard to find Christians who disagreed with this once one moves outside orthodox circles. Bart de Ligt (1883–1938), theologian and clergyman of the Reformed Church, was an avowed pacifist and anti-militarist, and never refrained from spreading his anti-militaristic views, whether from the pulpit or as leading political voice in the small (but vocal) ‘Bond van Christen-Socialisten’ (Christian Socialist Union).35 Wars are never in accordance with justice, he stated, for wars are intrinsically unjust. We should not talk of the possible results of wars, but of their nature, for in war ‘justice is trampled by blind force’.36 Even if the Bible shows that war is forever – a fact he doubted – this did not mean that it was therefore the responsibility of Christians to make sure that it would be. He even accused politicians such as Kuyper and de Savornin Lohman of a kind of veiled militarism, due to their eagerness to expand army and fleet.37

This may not have been entirely fair of de Ligt. People such as Kuyper and de Savornin Lohman had indeed argued for a powerful Dutch army, but their logic has been consistent with non-aggressive policy. Wars will happen no matter what we do, they would argue. So we had better make sure that we were capable of defending ourselves.38 And it was not just the neo-Calvinists who held this view. Jan Rudolph Slotemaker de Bruïne (1869–1941), for instance, a clergyman of the NHK, wrote in Stemmen des Tijds that the well-known Christian pacifism of the ‘turn the other cheek’ kind was meant to apply only at a personal level. The state, in its task of maintaining justice at all times, may indeed require force to do so, and cannot operate on moral convictions alone. In failing to arm itself properly, it would in effect submit and bow to the forces of injustice.39 In Roman Catholic circles similar views could also be found. For instance, the bishop and philosopher Johannes D.J. Aengenent (1873–1935) recommended Bavinck’s 1914 essay and stated that God could very well choose to allow for the existence of disasters that resulted from human sin, so long as these could be used as a means of achieving some higher purpose.40

Justice and the Great War

‘A disaster resulting from human sin’ appears to be the consensus view of the First World War among Dutch theologians, and it is difficult to find even a single Dutch author willing to defend the war as just. This is not the case in the warring nations, for obvious reasons. In England and Germany, for instance, the clergy often took the side of their country and defended its involvement in the conflict as just, condemning the war effort of the other side as evidently unjust. So the Germans liked to portray their own Kultur as a superior and more purely Christian one, fighting against the watered-down, liberal culture of England and France, while the English tended to argue that they were only doing their duty of protecting international law by graciously defending Belgium, which the Germans had so brutally and unjustly invaded.41

The Dutch tended not to buy into this. During the months following the outbreak of the war, the columnists in Stemmen des Tijds were quick to reject the English and German accounts and instead blame the war on the prevalence of a number of ideologies of modern times. Pieter A. Diepenhorst (1879–1953) held that both England and Germany were guilty of militarism and imperialism and were thus hypocritical for blaming each other, and the journalist of the Standaard Hendrik Lodewijk Baarbé accused the British of using militarism to combat militarism.42 The cultural criticism and condemnation that had been relatively mild in the GKN in the years before the war, thus flared up as soon as the first guns were fired.

Challenges to Christian authority had come in various guises during the nineteenth century, a period that can be characterized in terms of the emancipation of a vocal middle class and the rise of the liberal nation state, bringing with it a plethora of political, philosophical and religious innovations.43 The influence of Hegel is hard to overstate, and his views on history as a progressive, dialectical unfolding were highly influential throughout Europe. This gave a new impulse to biblical criticism, as biblical stories could now be seen as admirable but crude and inaccurate attempts of poorly equipped people to convey deeper religious truths, an approach that had followers among Dutch theologians of the modern school. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution formed a similarly devastating critique on biblical authority, especially in the form of the English philosopher Herbert Spencer (1820–1903), who tweaked Darwin’s ideas and transferred them into the realms of politics and sociology. The result was a system in which a laissez faire policy would lead to inevitable moral, intellectual and societal progress. Kuyper, who had initially placed Darwin in the tradition of Hegel, eventually came to associate him with Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844–1900), with whom he shared the idea of a world without purpose. Nietzsche’s nihilistic views concerning morality and human development indeed struck fear in the heart of many an orthodox believer, and for them he became a kind of model for everything that was wrong with modern society.44

Most importantly for the neo-Calvinists, all these developments resulted in ultimate authority being placed in the hands of man. Europe had thus sought to ground authority in human society and discourse, rather than submitting itself to God’s Word and judgement. International law, so essential for the maintenance of peace, was outvoted time and again by feelings of nationalism. The war was the result of arrogance and the idea that ‘power begets justice’.45 GKN clergyman Bastiaan Wielenga (1873–1949), as so many, believed that the main cause of the war stemmed from the pervasive influence of Nietzsche, whom he saw as the main inspiration for militaristic ideas in Europe. This had led to a form of state egoism, or politics without morality, where nations served no higher law than that of self-interest.46 Bavinck identified a distinction between ethics and politics that he took to be a fairly recent phenomenon. The state should use its power to preserve justice, but the decoupling of ethics and politics had led to international politics being systematically divorced from the preservation of justice. If it was in a nation’s interest to invade another, there was no reason for it not to.47 In 1919, Bavinck summed it up nicely when he wrote that it was a certain mentality that had set the world on fire. It made no difference whether one chose Darwin (England) or Nietzsche (Germany), for both preached the gospel of war.48

This does not mean that no one picked a side. Kuyper, for instance, made no secret of his preference for a German victory, but his position was chiefly pragmatic, as he believed that the Dutch cultural and economic ties with Germany meant that the Netherlands would benefit more from a dominant position for Germany than one for Britain. Moreover, Kuyper had long felt that Britain, as an aggressively colonial naval power, posed a significant threat to the Dutch overseas territories. The British had indeed reinforced this belief in 1899–1902 by annexing two former Dutch colonies in what is now South Africa during the Second Anglo-Boer War. This episode had greatly troubled Kuyper when he had been prime minister on behalf of the ARP.49 Most cherished the neutral position of the Dutch, however, and held that it would be unwise for their country to choose a side in the conflict. Indeed, for some time during the war, the Dutch saw themselves as ideal mediators between the warring nations, due to the long tradition of neutrality in European conflicts, and the successful and peaceful living side by side of people with fundamentally different ideas and backgrounds. However, this enthusiasm eventually waned when attempts at negotiating a peace deal failed, and the situation at home became more and more difficult. The Dutch finally turned inwards rather than outwards, focusing on self-preservation.50

In short, the general question of justice and the war was not a particularly difficult one for the GKN. Wars could be just, as they had been arguing for years, but this war was not, as it was caused by the same ideas and mentality that neo-Calvinism had been constructed to resist. The really difficult question, as Bavinck posed it in his 1914 essay (quoted above), was ‘how to give it a place in our reasonable, moral, Christian worldview’, for it seemed ‘that it no longer fits in our life, and falls outside the framework of this age’.51 It is this second aspect of the ‘problem of the war’ that proved to be quite intractable for the neo-Calvinists, in part due to the answers they had given to the first.

The Failure of Orthodoxy

World War I may be said to have involved four Christian ‘emperors’.52 Why, asked Bart de Ligt in 1914, are the [national] churches with these emperors? His answer was simple: not because God was with the emperors, but because God was not with the churches, which have preached a caricature, a God of war.53 Indeed, De Ligt largely held the churches responsible for the war, for they too had fallen for the materialism of the time and had remained silent despite all the injustice and violence.54 As pointed out by Koops, similar ideas were commonly expressed from the pulpit of the GKN.55

Alexander W.F. Idenburg (1861–1935), close friend and ARP-colleague of Kuyper, and Governor-General of the Dutch East-Indies, commented on the sinking of the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania by a German submarine, by writing that this was indeed a terrible thing, but no more terrible than the systematic starving of the German people by the British naval blockade.56 Not only did both sides fight brutally and mercilessly, but yet another source of great chagrin and distress for many was, what Idenburg – in a letter to Kuyper – called the ‘unnatural grouping of allies’, referring to the alliances between Christian and non-Christian states on both sides of the conflict (England with Japan, Germany with the Ottoman Empire).57

It was difficult to make sense of such an unusually terrible war, but the idea that the war could function in somehow cleansing society of its ills was occasionally used to give meaning to it. The seed of this thought was expressed by Kuyper, who was in Germany when the Kaiser declared war on the French. Due to the chaos of mobilization it took him no less than four days to return home, and still in shock a few weeks later, he wrote to Idenburg:

Everything here feels as though struck by God’s own hand [...] Stress governs our lives. All are disturbed and terrified. Economically and financially too, many have perished. [...] I do not know how to get through this. And yet all this is wonderful. It is so healthy. Everything was corrupted. Now comes the great operation, and then follows the cleansing. God comes to rid us of our own social degeneration in the most terrible way. I can be grateful, but the struggle will be immense.58

But Kuyper never further developed this notion of cleansing, and at any rate it was far less common among theologians in the Netherlands than in (say) England, where the Anglican Church felt that its direct involvement in the war effort through war chaplains and public opinion making gave it a real chance at regaining some of the socio-cultural influence it had lost in the decades before.59 In the Netherlands the churches had a much harder time staying afloat. After an initial spike in church attendance – huge masses flocked to the churches as the war broke out – things quickly returned to normal as soon as it became clear that the Netherlands would probably remain neutral. Soon the churches got into trouble, as the war situation and mobilization led to shortages of personnel, goods, etc. In the end the churches could do little more than try to maintain existing order.60 By 1917, Kuyper wrote that ‘it cannot be said of the European war that through it the Christian character of our State has regained its strength’.61 Bavinck seems never to have had much sympathy for the idea of cleansing through this war. In 1914 he predicted that the war would be bad for Christianity, and in 1919 he confirmed that indeed it had been. Even his hopeful (though perhaps somewhat vague) suggestion in the 1914 essay that the war might bring something good by rekindling the ‘indestructible life force’ in people, is absent from his 1919 essay.62

It was in fact much more common to look at the terrors of the war, in combination with the social ills brought on by modern society, as signs of the immanent end-times and the Second Coming of Christ. Such ‘eschatological’ themes were a broad European phenomenon from the beginning of the twentieth century, with the general pessimism of the fin de siècle, but saw a boom during (and after) the war.63 Some clergymen exhorted people to actively prepare themselves for the end of times. In a passionate piece that appeared in 1915 in Stemmen des Tijds, Wielenga argued that the influence of Nietzsche on European thought and culture would lead to the moral and social downfall of society, and later he would write of the ‘blonde beast’, and argue that this war pointed towards the final war between good and evil.64 For Kuyper, eschatology became a source of meaning and consolation. In a speech held on 24 November 1915, to celebrate the 25-year anniversary of a church youth organization, he spoke longingly of the Second Coming:

I hope that you will not exist for another 25 years. I would find it much greater if, before we get to another 25 years, the end of the world would have come [...] This question is all the more relevant since our Saviour predicted that wars and rumours of wars would precede the end and bring us to the end. [...] Oh, let it be your prayer: ‘Come, Lord Jesus, yes come swiftly’.65

Bavinck shared Kuyper’s despair about the state the world was in, but was less willing to talk of the end times. By 1919, however, he did seem to have found at least some solace in the belief that, in some sense, this is how it was supposed to be:

The limited influence had by Christianity on the diminution of war is, for its members, a cause for shame and sadness, but it can hardly be very disappointing given the condition the world and humanity are in according to the Bible, due to their sinful nature. [...] Without a doubt, God is capable of leading to good end what humanity has made for evil. This remains a consolation amidst the greatest suffering.66

I take this to be Bavinck’s solution to the ‘problem of the war’ he posed in 1914 (as quoted in the introduction to this paper) – and a seemingly unsatisfactory one at that. It was not the question of war and justice (the neo-Calvinist tradition had a clear answer to that), or that of the cause of this war (tradition had no trouble proposing causes for such a conflict), but that of the meaning of the war; how, in Bavinck’s words, ‘to give it a place in our reasonable, moral, Christian worldview’.67 It seemed indeed to fall ‘outside the framework of this age’68, and the tradition of the GKN appeared not to have an answer to it.

The Reinvention of Tradition

When the war had finally come to an end, it was time for the churches to lick their wounds and think about what to do next. Apart from a handful of positive effects, such as the spectacular progress made in aviation and other technologies, not much good could be said about the beginning, middle, or end of the war, Bavinck wrote.69 Pieter Jelles Troelstra, leader of the Dutch social democrats, did not help by declaring it was just the right time for a socialist revolution in the Netherlands. The attempt failed spectacularly, but was seen by some as a general symptom of the moral degeneration that had not reversed or slowed down but sped up during the war.70

In general, Kuyper and Bavinck were rather pessimistic about the future of their church, much more so than they had been before the war. On 27 October 1917, in an article in the newspaper De Amsterdammer, Kuyper wrote that any people who imagined a growth in Protestant church life from the war were fooling themselves.71 Bavinck went so far as to say that of all the disasters the war had brought with it, the loss of religion, both nationally and internationally, had been the most devastating.72

Not everybody shared their pessimism. Orthodox Reformed theologian Slotemaker de Bruïne had written a book back in 1910 entitled, Het Geloof aan God in de Twintigste Eeuw (‘Belief in God in the Twentieth Century’), in which he tried to give a general evaluation of the state of religiosity the world was in. He believed to be able to prove that the twentieth century would be one of religious revival, as it was pessimistic and looking for God. The only solution to the problems the modern world confronted us with, was to be found in the Bible, for all of the nineteenth century ideologies that had tried to do without it, had been found wanting.73 Slotemaker de Bruïne held on to this view during the war, affirming in Stemmen des Tijds in 1916 that ‘Our time is religious. [...] Religions now have a good chance. Materialism satisfies nobody’.74 And finally, in his 1918 essay De Invloed van den Oorlog op het Godsdienstig Denken (‘The Influence on the War on Religious Thinking’), he wrote that the war had made people more serious towards ethical and religious considerations, and had made it possible for the churches to reclaim their social roles. ‘Thus the war has expanded religion’.75 Bavinck was less enthused by this renewed religiosity, and commented:

It is worth noting that this religious belief usually has a general character and contains very little that is Christian; guilt and a desire for salvation are rarely heard of; the religion is often vague and superficial. [...] And while the war persisted, the religious awareness weakened and was in many cases even replaced by apathy, doubt and unbelief. Due to this war and its many woes, thousands upon thousands have fallen into scepticism, materialism and atheism, for how could so much suffering be made consistent with the love of an all-powerful Providence?76

And Kuyper, in 1917:

It is true that the great majority of the population is still counted as belonging to a Christian Church community. In 1909, only 290,960 people did not belong to any Church community, but it certainly does not follow from this that the rest professed belief in Christ. Especially among the official and socially important members of more than one Church, the denial of Christ is often dominant, and philosophical or pagan conviction the rule.77

Kuyper and Bavinck were quite right in their perception that any rise in religiosity during the war certainly had not favoured the traditional churches – it was spiritualist movements and new religious sects that were flourishing due to the conflict.78 In addition, the proportion of the Dutch population not affiliated with any church increased from 5% to 14% between 1909 and 1930, a rise probably not entirely unrelated to the war.79 This does not mean that the GKN faced imminent crisis: the church kept growing steadily during the interbellum, even if only due to relatively high birth rates.80 But social boundaries had become porous due to the hardships of the war, and certainties had turned into doubts.81 Especially during the twenties, there were complaints everywhere of loss of authority, not least in the churches, and there was a general sense that the traditional answers no longer sufficed.82

Conclusion

A significant part of the hardships the GKN endured during and after the First World War, and its failure to act in any way so as to convince people that they were doing everything they could against it, were no doubt caused by the material and personal shortages it had to endure, as shown by Koops.83 But I would argue that part of it was caused by the position that neo-Calvinist theologians took – and indeed had to take, given their theological background – with respect to the conflict. They did not defend the war effort of any nation involved in the conflict, but they did defend war. Their attempts to give meaning to it were unsatisfactory to many. It is not very surprising, therefore, that in a 1924 article in the newly founded journal Antirevolutionaire Staatkunde (‘Antirevolutionary Politics’), Idenburg sounded genuinely annoyed in his reply to those who categorically rejected war from a Biblical point of view:

In itself this argument is evidently one-sided and superficial. It must be said once more: God’s love, however blissful for His children, is not sentimentality, not weakness, that prevents wrath and counteracts judgement, that brushes justice aside and leaves the assailing of God’s holiness unpunished. Whoever believes this does not live from the Holy Scripture, but from personally wrought conceptions. [...] We do not glorify war, but we accept it as a judgement of God. We do not explain away all the horrors that take place, but they make us shudder – also because they give us a vision of the depth of sin. With all our strength we wish to support everything that can contribute to the reduction of war and let not brute force but holy justice rule on earth.84

Kuyper and Bavinck had tried to renew Calvinism and had defined their theological and cultural views in response to specific problems posed by the nineteenth century. The neo-Calvinist world had an integrated character, with many theologians holding University positions as well as political or church positions, and not rarely a combination of those (as with Kuyper and Bavinck). But their theology could not adequately deal with the First World War, and it was now up to a new generation of neo-Calvinist theologians to reformulate orthodoxy in response to the problems posed by the twentieth century. Kuyper and Bavinck were not forgotten, and the youth of the GKN still drew inspiration from their work.85 But some of the confidence had disappeared, and with their deaths (in 1920 and 1921, respectively), an era had come to an end.