|

|

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

| Year : 2015 | Volume

: 3

| Issue : 1 | Page : 14-19 |

|

Experience of HIV voluntary counseling and testing in antenatal women at a tertiary health centre of North India

Saroj Singh, Shikha Singh, Ruchika Garg, Indira Sarin

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sarojini Naidu Medical College and Hospital, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India

| Date of Web Publication | 9-Nov-2015 |

Correspondence Address:

Indira Sarin

B.27/88, 34 A1, Wel View Apartment, Ravindrapuri Colony, Bhelupur, Varanasi - 221 005, Uttar Pradesh

India

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None  | Check |

DOI: 10.4103/2321-9157.169177

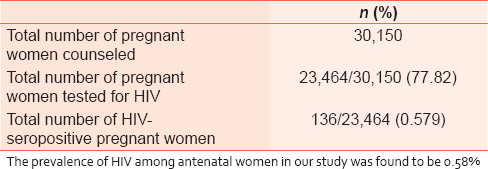

Background: Integrating routine HIV counseling and testing as a mandatory part of antenatal care in India has led all pregnant women enter into the prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV program. Despite such strategies, the effective execution and uptake of these programs remains a major obstacle. It is thus, important to understand the experiences of pregnant women undergoing HIV testing to detect the flaws on the part of the provider and the benefiter and eliminate them to strengthen the PMTCT services. Aim: We studied the acceptability of HIV voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) in antenatal women attending a tertiary health center of the North India. The impact of the sociodemographic factors on HIV prevalence and uptake of PMTCT was also studied, and the possible reasons for dropouts were determined. Methods: Pretest counseling was performed, and sociodemographic data and blood samples were collected from the consenting antenatal pregnant women. Samples were tested for HIV antibodies as per the World Health Organization guidelines. Data were analyzed and presented as mean, percentages, and tables. Results: Of 30,150 pregnant women counseled, 23,464 (77.82%) underwent testing. 136/23,464 women tested seropositive. The prevalence of HIV in antenatal women was found to be 0.58%. The majority of these women were young and belonged to the age group 20–24 years (0.23%). 22% refused testing, the reasons for which were sought. Strong associations were found between the HIV seroreactive status and marital status, low education status, low social class, high parity, and unemployment. Conclusion: To eliminate pediatric transmission of HIV and to create more awareness regarding HIV infection and MTCT, there is a need to make VCT and PMTCT programs more acceptable to the population. The observations found in the study were consistent with the national projections.

Keywords: Antenatal women, HIV prevalence, prevention of mother to child transmission, tertiary care, voluntary counseling testing

How to cite this article:

Singh S, Singh S, Garg R, Sarin I. Experience of HIV voluntary counseling and testing in antenatal women at a tertiary health centre of North India. J HIV Hum Reprod 2015;3:14-9 |

How to cite this URL:

Singh S, Singh S, Garg R, Sarin I. Experience of HIV voluntary counseling and testing in antenatal women at a tertiary health centre of North India. J HIV Hum Reprod [serial online] 2015 [cited 2018 Aug 6];3:14-9. Available from: http://www.j-hhr.org/text.asp?2015/3/1/14/169177 |

| Introduction | |  |

HIV continues to be one of the greatest health challenges in the world with approximately 35 million people living with HIV infection globally in 2013.[1] India has the third largest HIV epidemic in the world.[2] In India major route of HIV transmission is through sexual contact (85.6%). Nearly, 5% of infections are attributable to mother to child transmission (MTCT).[3] The epidemic disproportionately affects women, who account for 39% of the total infections in the country.[2] Women stand at a higher risk of HIV infection and are a source of transmission to their children, thus forming the focus of most AIDS control programs aimed to meet the goal of achieving virtual elimination of pediatric HIV. Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) has been identified as an effective tool in reducing HIV transmission. So far, very few studies have been conducted citing the acceptance of VCT and prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) programs from this part of India. Undertaking this study was, therefore, important to understand the current trend of HIV seroprevalence and its sociodemographic impact, to formulate better strategies for success of PMTCT in India.

| Methods | |  |

Setting

Ours is a tertiary care referral hospital in the North India where mostly patients referred from other centers undergo antenatal checkups. Most of the general antenatal patients undergo antenatal checkups at the adjoining district hospital. The present study sets out to determine the impact of VCT in PMTCT of HIV and to simultaneously identify the lacunae in the prevailing PMTCT programs.

Patients and period of study

Pregnant women visiting and registering at the antenatal clinic of this hospital are routinely advised to undergo HIV screening after pretest counseling done by trained field workers and informed consent. The local pathological laboratory of our department caters these laboratory services to all such patients, and the tests are carried out as per the guidelines laid down by the National Aids Control Organization, India.[4] The results were collected from all pregnant women tested in this laboratory, and no selection bias was observed.

The findings were analyzed over 9.5 years from October 2005 to April 2015.

Ethical consideration

Informed written consent was obtained from each participant after pretest counseling, and the participants were free to withdraw from the test anytime they wanted. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Institute.

Testing procedure

If the participant agreed to the testing, she was referred to the laboratory technician who performed a rapid HIV test (SD BIOLINE HIV - 1/2 3.0 Rapid Test Procedure; bio standard diagnostics Pvt Ltd., India). If the participant tested positive for HIV or had an indeterminate test result, the result was checked using the Combaids – RS Advantage-ST HIV1 and 2 Immunodot Test Kit (Span Diagnostics Ltd., India). Rapid test kits were kept under optimal conditions and used before the expiry date. Results were read under good illumination. Test quality was ascertained by running regular negative and positive control tests. The results were obtained in 5–10 min after the first test and in about 20 min after the second. The first rapid test kit used was previously evaluated by the Consortium of National Reference Laboratories of Government of India and was found to have high sensitivity (≥99.5%) and specificity (≥98.0%); and the second test showed 100% sensitivity and specificity and intra- and inter-run precision. Samples giving positive results were reanalyzed using the COMBAIDS – RS Advantage-ST Immunodot Test Kit. Standard biosafety, record keeping, and client confidentiality procedures were observed.

Statistical analysis

The results were presented in percentages and means. Simple inferential statistics were used. Qualitative data collected from group discussions were analyzed through detailed content analysis and ethnographic summary.

| Result | |  |

Data were collected, and analysis was performed on 30,150 pregnant women visiting the antenatal clinic during the period of October 2005 to April 2015. These women were provided voluntary pretest counseling for HIV Testing, out of which 23,464 (77.82%) consented for testing. About 22% of pregnant women opted out from testing and hence we could not assess the seroreactivity in these women.

136 out of 23,464 women, that is, (0.579%) tested seropositive for HIV antibodies in the double rapid tests [Table 1]. | Table 1: Acceptance of HIV testing among pregnant women who were counseled

Click here to view |

The age of subjects ranged from 15 to 42 years with a mean age of 26.10 years. Most of these women, (10,839) 46.3% were in the age group of 25–34 years followed by 20–24 years, (10,373) 44.2%, >35 years (5.1%), and least in 15–19 years (4.4%).

Among the seropositive women, the majority (38.9%) were aged 20–24 years with the prevalence of this population being 0.23%, followed by the age group of 25–34 years (36%), the prevalence being 0.20%, then >35 years (18%) the prevalence of 0.076%, and in the age group of 15–19 years (11.76%) with the prevalence of this category being the lowest of 0.06% as shown in [Table 2].

The mean age of the HIV-positive women was found 26.29 years.

[Table 3] shows the socio-demographic characteristics, 21,583 women (92%) tested were married, and 89% (121 out of 136) of HIV seropositive females were found to be married. Hence, marital status emerges out to be a strong associated factor in HIV spread. The majority of pregnant women 21,579 (92%) were unemployed, so were the seroreactive patients 86%. Only 1.5% of HIV-positive pregnant women had higher education, 10.9% had secondary education, 16.4% received no education at all, as against a majority of 71.2% who had received only primary education. As expected, a major chunk of HIV reactive antenatal women population belonged to the lower socio-economic class (81.5%). Of the screened women, most of the HIV reactive ones were found to be bearing pregnancy 2nd time or more (54.4%), however, primigravidas falling in seroreactive category were also not lagging much behind (38.2%), and the grand multiparas were 7.4% most of the HIV reactive pregnant females visited our clinics in the third trimester of pregnancy (74.3%), either this was taken on their first visit or last.

102/136 seroreactive women (75%) accepted to utilize the PMTCT facility.

| Discussion | |  |

India has a low HIV prevalence of 0.3%.[2] Yet, in terms of individuals infected, it is home to the third-largest number of people living with HIV in the world. Sexual contact is the most important route of HIV transmission in India. MTCT is by far the most important route of HIV spread in the pediatric population (90%).[5] The transmission of the virus from the mother-to-child during pregnancy, labor, delivery, or breastfeeding is called MTCT.[3] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), globally, an estimated 2.1 million individuals became newly infected with HIV in 2013. This includes over 240,000 children (<15 years), and most of them were from developing countries and were infected by their HIV-positive mothers during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding.[1] It is estimated that out of 27 million pregnancies every year, nearly 49,000 occur in HIV positive mothers.[3] However, out of these 27 million pregnancies, only about 52.7% of attend health services for skilled care during childbirth in India. Of those who availed health services, 8.83 million antenatal patients received HIV counseling and testing (March 2013) of which 12,551 pregnant women were detected to be HIV positive. Of the 12,000 pregnant women found to be living with HIV, 84% were provided antiretroviral (ARVs) drugs to prevent MTCT of HIV.[6]

It is well established that MTCT can now be reduced to less than 2% from 25% to 30% earlier.[7] With the use of effective antiretroviral treatment (ART) and non- ARV strategies, MTCT has been virtually eliminated in developed countries. However, prevention of transmission through breast milk and formulating an effective ARV regimen has remained a major challenge for the developing countries.[8] According to WHO, in 2013, 67% of pregnant women living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries (970,000) received ART to avoid transmission of HIV to their children. This is up from 47% in 2010.[9]

The Indian government is committed to eliminating new HIV infections among children by 2015. India's PMTCT program started in 2002. To date, there are over 15,000 sites offering PMTCT services based on 2013 WHO guidelines, the program initiates ART for all pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV regardless of cd4 count or stage of infection.[9] In 2013–2014, 9.7 million pregnant women accessed HIV testing against a target of 13.2 million – a coverage of 74%.[9]

VCT has proved to be of promising help in reducing HIV transmission and has shown to provide behavior change and emotional support for those who test positive for HIV1. At the same time, it is feasible and acceptable in reducing perinatal transmission of the virus. In order to improve the effectiveness of India's PMTCT program and to meet the goal of achieving the virtual elimination of pediatric HIV in the country, it is important to devise appropriate evidence-based strategies. Ideally, all women should be screened for HIV before delivery during an initial prenatal care visit so that potent ART can be started in those found to be HIV infected. VCT is recognized as a priority in national HIV programs because it forms the gateway to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, treatment, and support interventions but this has still not become embedded in peripheral health facilities in India. It is critical to increase the prenatal detection rate of HIV-infected pregnant women so that effective interventions can be delivered.

The availability of affordable, accurate, reliable, simple, and rapid HIV tests providing results within the time frame of a single brief antenatal visit for single or a small number of clients significantly facilitates PMTCT programs by reducing travelling time and expenses. The sensitivity and specificity of these tests are greater than or equal to 99% and similar to those of ELISA. The rapid HIV tests are most suitable in developing countries where the majority of pregnant women are attended by traditional birth attendants, the pregnant women use the formal health sector only as a backup arrangement. If pregnancy and labor progress as expected, the pregnant women attends a local formal health post once at booking which mostly may be late in pregnancy. In these circumstances, rapid HIV tests afford the opportunity to screen for HIV in women attending peripheral units and provide results during the same visit.

This study recorded the experiences of pregnant women which showed their apprehension regarding getting tested. This was found to be attributed to the fear of being tested positive, and the stigma attached to HIV.

We found the overall prevalence of HIV among pregnant women to be 0.57%. The national prevalence in antenatal women was 0.4%, which is lower than our finding.[9] One reason for this could be that our center being a referral tertiary health center, so most of the seroreactive cases are referred here which could be a reason for the overall higher prevalence.

Our study supports that HIV prevalence is higher in the reproductive age group when there is maximal sexual activity. The age wise distribution showed a higher prevalence of infection in young reproductive population, being maximum in age group of 20–24 years (0.23%) followed by 25–34 years (0.20%), >35 years (0.08%), and 15–19 years (0.06%). This observation is consistent with the national data, where the prevalence of HIV in India among 20–24 years is 0.18% and that among 15–19 years old is 0.04%.[3]

Marital status was seen to have a strong relation with the HIV status of the study participants (89%). Also, in Indian patriarchal society, women especially of the lower social class cannot influence their husband's behavior and demand safe sex.

This study also depicts that the infection of HIV is more prevalent among the pregnant women who had no formal education at all (16%) or who did not complete secondary school education (71.2%). This is in agreement with the study that reported that women having higher education have better knowledge of HIV transmission in contrast, the lower levels of female education promotes ignorance about the transmission and prevention of HIV infection especially in the unborn child. Most of the women could not complete secondary education. This may explain their being unemployed (86%) and also belonging to the low socio-economic class (81.5%). Unemployment being associated with poverty, and has also been linked with unsafe sex for money, thus, increasing the risk of HIV infection.[10],[11]

Also, in this study it was found that most women who attended our antenatal outpatient department were multigravida (54.4%), while primigravida who might be at higher risk of HIV infection by virtue of relatively younger age and the associated risky sexual behaviors, do not utilize formal antenatal services.

Furthermore, those that utilized the services presented late in the third trimester (74.3%), when interventions could be late to address some adverse trends of HIV on pregnancy especially in resource-limited settings. Financial constraint, ignorance, and lack of awareness were cited as reasons for late and poor utilization of antenatal services. This is in synchronization with other studies.[12],[13]

The implementation of the government's mandatory screening policy, which explicitly states that universal HIV screening should be included as an integral component of routine antenatal care checkup, ensured that the women who are diagnosed with HIV would be linked to HIV services for their own health, as well as to ensure prevention of HIV transmission to newborn babies under the PMTCT program.

In this study, 22% of the initially counseled women opted out testing after HIV counseling. The reasons for dropping out were the taboo attached to HIV, apart from the ignorance and financial constraints. The factors that influence the acceptance of HIV testing and receiving test results including the counseling technique used, were suspicion of being already infected, fear of having to cope with the result should it be positive, fear of discrimination, domestic violence, or divorce. There is an almost hysterical kind of fear in India regarding the stigma and discrimination of HIV that the parents and in-laws can blame women for infecting their husbands, while children can be denied right to go to school, most women depended on their husbands and in-laws to take the decision regarding getting tested. This is in accordance with the findings of other authors.[9],[12]

While comparing group and individual pretest counseling techniques during the study, it was shown that there was a better patient acceptance of HIV testing following individual rather than group counseling. In our study, pretest counseling was partly provided as group counseling because lesser trained personnel are required and can be easily implemented at a public health set up. To maintain confidentiality, posttest counseling was always provided individually.

At the same time, it is important to understand that there is a strong need for couple counseling in order to make them understand the benefits of HIV testing, reducing HIV transmission, and helping couples to cope with the HIV seropositive status. Couple counseling and testing will also ensure inclusion of underserved couples, especially those who are less educated and economically disadvantaged. We can thus, identify discordant couples and offer methods to them for reducing risk and transmission within their relationships. The WHO recommends that couple testing be expanded in settings where routine HIV testing is offered, with support for mutual disclosure to empower couples to make informed decisions about HIV prevention and family planning. However, there is a need to assess the acceptability and impact of this effort among couples.[14]

Among the study subjects, VCT was found to be high so also the utilization of PMTCT services, 77% and 75%, respectively. The study shows an upward trend in the uptake of PMTCT program in this part of north India. This is in accordance with the national survey report.[2]

| Conclusion | |  |

For this part of the north India the prevalence in our study was found higher than that of the national survey because ours is a referral center with a higher input of HIV-infected pregnant women and the general population of antenatal women is being tested at adjoining district hospital. The acceptance of VCT was high so also was the uptake of PMTCT services.

Social and demographic factors plays an important role in the spread of HIV infection, knowledge about the transmission, awareness of self-status and protection, awareness regarding transmission to the baby and its protection, various government and government-aided programs and their uptake by pregnant women. The prevailing national PMTCT program is being mostly jeopardized due to a large number of women dropping out of the PMTCT cascade. In order to increase this uptake PMTCT programs can be integrated to demonstrate other health benefits to the mother and the child. It is imperative to look into alternative methods for the implementation of PMTCT programs in order to maximize the reach of services to HIV-infected women in the least cost. Involvement of the nongovernment organizations and national programs could maximize the reach of these services to infected women.

| References | |  |

| 1. | |

| 2. | Annual Report (2012-13), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, National Aids Control Organization (NACO); 2012-13.  |

| 3. | |

| 4. | Baveja UK. HIV Testing Manual, Laboratory Diagnosis, Biosafety and Quality Control. New Delhi:NACO - National AIDS Control Organization, HIV Testing Manual: Laboratory Diagnosis, Bio-Safety and Quality Control, NACO - National AIDS Control Organisation. p. 45-67. Available from: http://www.nacoonline.org/publication/7.pdf. [Last accessed date 2014 Jan 29].  |

| 5. | |

| 6. | |

| 7. | Cooper ER, Charurat M, Mofenson L, Hanson IC, Pitt J, Diaz C, et al. Combination antiretroviral strategies for the treatment of pregnant HIV-1-infected women and prevention of perinatal HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;29:484-94.  |

| 8. | Darak S, Panditrao M, Parchure R, Kulkarni V, Kulkarni S, Janssen F. Systematic review of public health research on prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in India with focus on provision and utilization of cascade of PMTCT services. BMC Public Health 2012;12:320.  |

| 9. | Annual Report (2013-2014) Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, National Aids Control Organisation (NACO); 2013-2014.  |

| 10. | Dandona R, Kumar SG, Kumar GA, Lakshmi V, Dandona L. HIV testing among adults in a high prevalence district in India. Natl Med J India 2009;22:289-93.  |

| 11. | Panditrao M, Darak S, Kulkarni V, Kulkarni S, Parchure R. Socio-demographic factors associated with loss to follow-up of HIV-infected women attending a private sector PMTCT program in Maharashtra, India. AIDS Care 2011;23:593-600.  |

| 12. | Rogers A, Meundi A, Amma A, Rao A, Shetty P, Antony J, et al. HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, perceived benefits, and risks of HIV testing among pregnant women in rural Southern India. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2006;20:803-11.  |

| 13. | Samuel NM, Srijayanth P, Dharmarajan S, Bethel J, Van Hook H, Jacob M, et al. Acceptance of HIV-1 education and voluntary counselling/testing by and seroprevalence of HIV-1 among, pregnant women in rural south India. Indian J Med Res 2007;125:49-64.  [ PUBMED]  |

| 14. | Orne-Gliemann J, Tchendjou PT, Miric M, Gadgil M, Butsashvili M, Eboko F, et al. Couple-oriented prenatal HIV counseling for HIV primary prevention: An acceptability study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:197.  |

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3]

|