|

|

| CASE REPORT |

|

| Year : 2013 | Volume

: 1

| Issue : 2 | Page : 77-81 |

|

Maxillary protraction in a case with miniscrew bone anchorage

Belma Isik Aslan1, Muayad A.M. Qasem1, Müfide Dinçer2

1 Research Assistant in Gazi University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics, Ankara, Turkey

2 Professor in Gazi University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics, Ankara, Turkey

| Date of Web Publication | 7-Aug-2013 |

Correspondence Address:

Belma Isik Aslan

Gazi University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics, 06510 Emek, Ankara

Turkey

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None  | Check |

DOI: 10.4103/2321-3825.116290

Four miniscrews were placed into the available inter-root area, two in the posterior and the other two in the anterior region in the maxilla as skeletal anchorage for facemask protraction in a girl 11 years and 11 months old with maxillary retrusion. No tooth support was used for the protraction of the maxilla. Applying orthopedic forces directly to the maxilla resulted in a 2 mm maxillary advancement. Undesired skeletal and dental effects of facemask therapy were eliminated with this new technique. Skeletodental changes in response to the miniscrew-anchored facemask treatment are reported in the present case. Keywords: Bone anchorage, class III correction, facemask, miniscrew

How to cite this article:

Aslan BI, Qasem MA, Dinçer M. Maxillary protraction in a case with miniscrew bone anchorage. J Orthod Res 2013;1:77-81 |

| Introduction | |  |

The major goal of maxillary protraction is to stimulate maxillary growth by applying orthopedic forces to circum-maxillary sutures. [1] Tooth-anchored facemask therapy is a common protocol for class III malocclusion with maxillary retrusion. [2] However, this system has undesirable effects including extrusion and mesialization of maxillary molars, proclination of maxillary incisors, and clockwise rotation of the mandible. [3]

In contemporary orthodontics, titanium miniplates are most frequently used as skeletal anchorage placed either into the infrazygomatic crest or lateral nasal walls of the maxilla; however, miniplates require surgical operation when placing and removing. [1],[4],[5],[6],[7] Therefore, in the present case, we aimed at designing a less invasive method for bone-anchored maxillary protraction by using miniscrews placed into the available inter-root area and evaluating the skeletodental effects of this system.

| Case Report | |  |

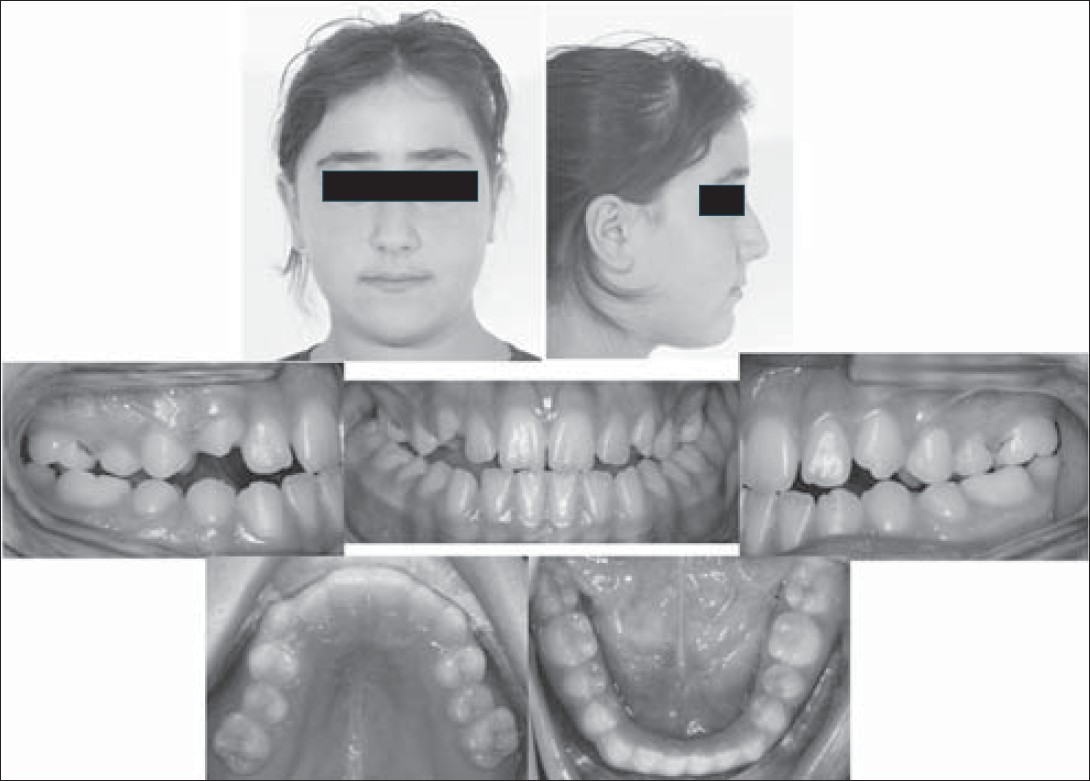

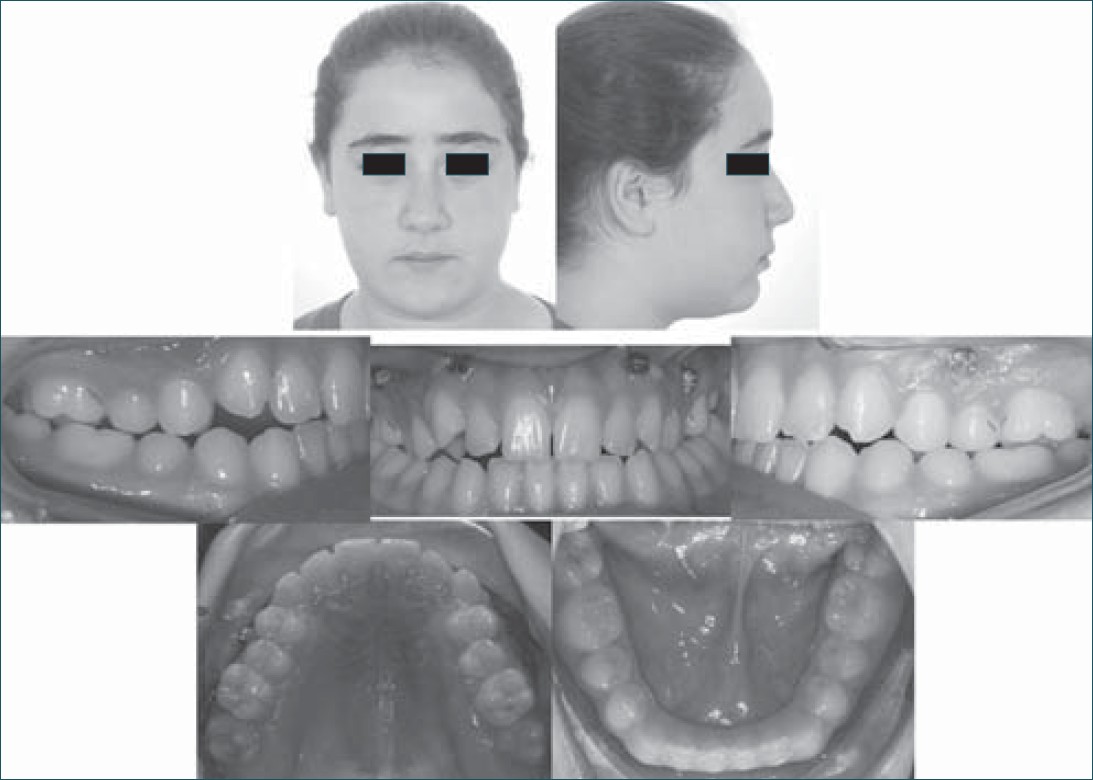

The patient in good physical health was a girl 11 years and 11 months old in pubertal growth period with no symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. Extraoral examination revealed a symmetric face and straight profile. Intraoral examination presented an angle class III molar and canine relationship with no midline deviation. Overjet and overbite were 0 mm. In the premolar area, a buccal crossbite was noted. Only the maxillary arch had a crowding of 2 mm [Figure 1]. | Figure 1: Intraoral and extraoral photographs of the patient at the beginning of face mask therapy

Click here to view |

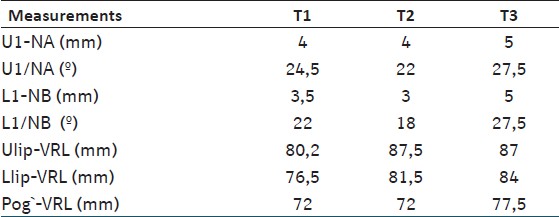

Lateral cephalometric analysis indicated a mild skeletal class III relationship with maxillary retrusion, increased mandibular plane angle, and ideal upper and lower incisor positions [Table 1].

Treatment Plan and Procedure

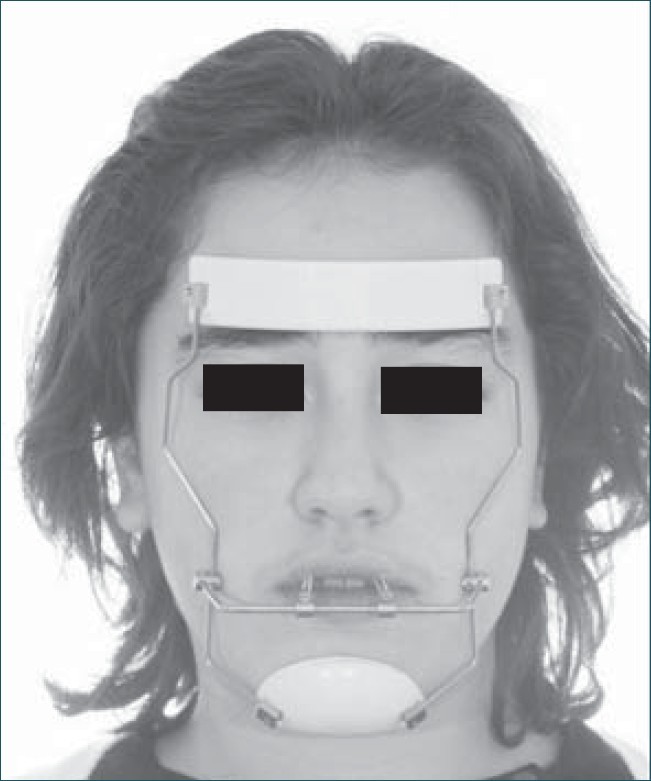

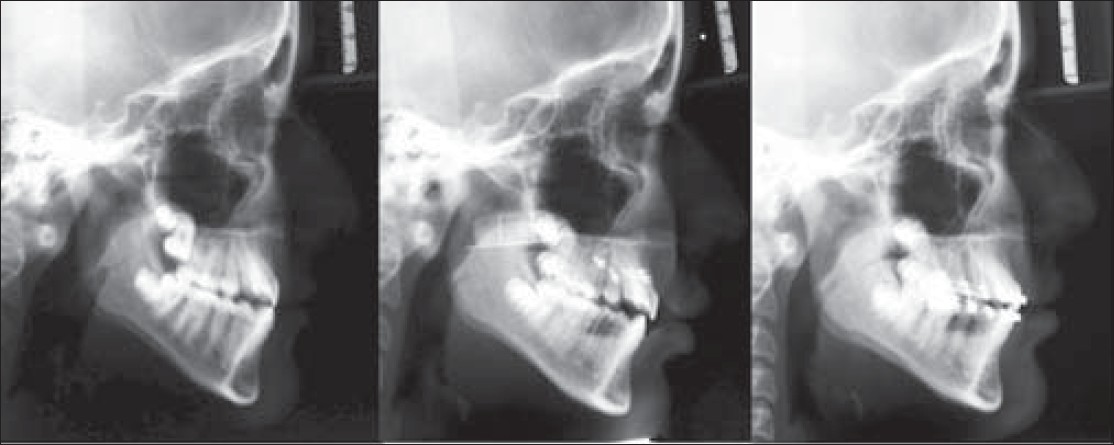

In the present case, bone-anchored facemask therapy was planned to be applied. Bone anchorage was supplied by four miniscrews (1.6×8 mm Metin miniscrews (MTN), Medifarm, Ankara, Turkey) placed into the available inter-root area, two in the posterior region and the others in the anterior region [Figure 2]. A week after placement of the miniscrews, an archwire was bent from a 0.021×0.025" stainless steel wire engaged passively into miniscrew slots and two hook shapes were given to the archwire in the lateral root region for facemask elastics [Figure 3]. Initially 200 g elastic force was applied bilaterally and after one week of traction when stability of the miniscrews was ensured, the force was increased to 300 g. Direction of the force was adjusted approximately 30° to the occlusal plane, and the patient was asked to wear the facemask at all times except during school. [Figure 4] After six months of facemask therapy, full fixed therapy was initiated. Lateral cephalograms of the patient were taken prior to (T1) and at end of facemask therapy (T2), and after six months of full fixed orthodontic treatment (T3) [Figure 5]. | Figure 2: Placement of four miniscrews between the available interroot area

Click here to view |

| Figure 3: 0.021×0.025" stainless steel archwire engaged passively into miniscrew slots

Click here to view |

| Figure 4: Facemask therapy with 30° elastic force traction to the occlusal plane

Click here to view |

| Figure 5: Lateral cephalograms of patient were taken prior to (T1) and at end of facemask therapy (T2), and after six months of full fixed orthodontic treatment (T3)

Click here to view |

Treatment Results

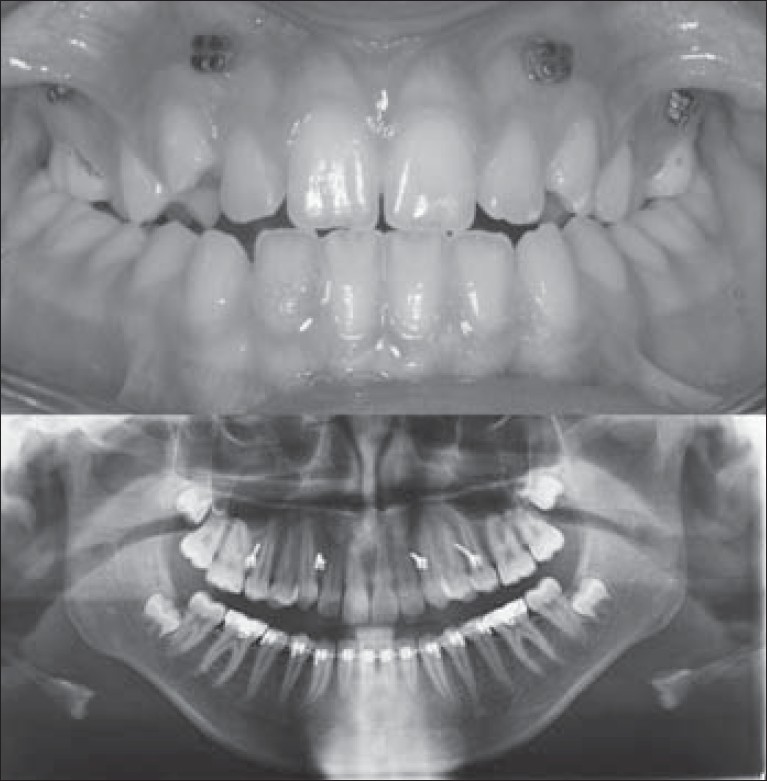

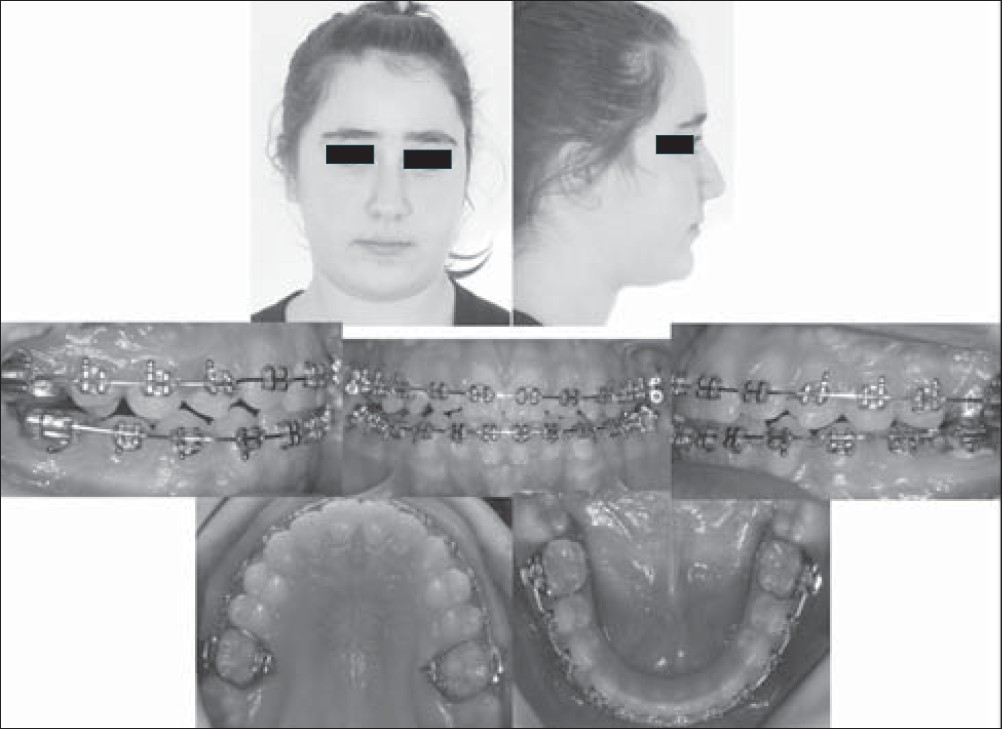

Miniscrew-anchored facemask therapy resulted in advancement of the maxilla with remarkable enhancement in soft tissue profile. Skeletal class 1, angle super class I molar, and class I canine relationships, and 3 mm of overjet and 2 mm of overbite were achieved. Arch perimeters were preserved [Figure 6] and [Figure 7]. During facemask therapy, total cephalometric superimpositions revealed maxillary advancement without any rotation of the palatal plane. The mandible moved vertically [Figure 8]. Local superimpositions revealed stabile maxillary molar and incisor positions [Figure 9]. After six months of full fixed therapy, slight forward growth of the maxilla and more pronounced forward movement of the mandible were observed [Figure 8] and [Figure 10] and [Table 1] and [Table 2]. | Figure 6: Intraoral and extraoral photographs of the patient at the end of facemask therapy

Click here to view |

| Figure 10: Intraoral and extraoral photographs of the patient at the end of sixth month of full fi xed therapy

Click here to view |

| Table 2: Dental and soft ti ssue measurements of the pati ent at T1, T2 and T3

Click here to view |

| Discussion | |  |

In previous studies, successful maxillary protraction was achieved with miniplate anchorage; however, miniplates require surgical operations while placing and removing. [1],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8] Therefore, we intended to develop a less invasive technique for bone anchorage in which four miniscrews were placed into the available inter-root areas.

In the present case, we preferred bone anchorage because the patient was at permanent dentition. Better skeletal changes have been demonstrated at earlier ages with conventional facemask therapy. [9] Therefore, tooth-anchored facemask treatment would probably result in dental compensation and loss of anchorage.

In this case, miniscrews were placed in the available bone area between roots in the anterior and posterior regions. There would be a limitation in timing the treatment for this technique because it would be risky to place miniscrews in mixed dentition due to premolar tooth follicles; so, clinicians should be cautious in selecting cases.

In our case, 300 g of force was applied per side and all the four miniscrews were stable during the protraction period. It has been reported that moderate loading forces are adequate for maxillary growth. [8]

In the present case, 2 mm of maxillary protraction was achieved. In previous bone-anchored studies, the amount of maxillary protraction varied between 2.0 and 8 mm. [1],[4],[5],[6],[7] It was suggested that approximately 3 mm of maxillary protraction can be achieved using bone anchorage. [7] The limited amount of protraction in our case is related to severity of the case.

Traditional facemask therapy usually results in counterclockwise rotation of the palatal plane and posterior rotation of the mandible. [1],[6],[9] In the present case, there was no anterior tipping of the palatal plane which could be achieved by protracting the maxilla near the center of resistance of the maxilla. Orthopedic force was applied between the hooks of the archwire in the lateral region and facemask with a direction of 30° downward and forward from the occlusal plane, as recommended previously. [10] In other bone-anchorage systems, slight anterior rotation of the palatal plane has been reported. [1],[4],[5],[6],[7] This rotation effect was found to be greater in conventional facemask systems. [1],[3],[6],[9]

In the present case, both posterior and anterior facial height increased, which is a common effect of all variations of facemask treatment. [1],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[9] Although there was a slight decrease in SNB due to the forward movement of nasion, the mandibular plane angle decreased which is an advantage in class III high-angle patients. [1],[4],[5],[6],[7]

In our case, undesired dental movements were eliminated, similar to other skeletal anchorage studies. [1],[4],[5],[6],[7] Only the mandibular incisors were uprighted slightly due to chin cup effect of the facemask, as reported previously. [6]

In this case, forward movement of the upper lip was achieved, resulting from maxillary protraction. Improvement of the lower lip was also observed due to the growth and develepment of the soft tissues. However after six month of full fixed therapy, there was a regression in lip positions due to forward growth of the mandible.

The application for miniscrew-anchored facemask treatment might be a choice for growing skeletal class III patients in permanent dentition with congenitally missing teeth cases or increased vertical growth patterns. Miniscrew anchorage provides maxillary protraction and eliminates undesirable skeletal and dental effects of facemask therapy without surgical operations. Our case was a mild skeletal class III patient; a randomized clinical trial on a larger sample is the next step to study more apparent effects of this technique.

| References | |  |

| 1. | Kircelli BH, Pektas ZO. Midfacial protraction with skeletally anchored facemask therapy: Anovel approach and preliminary results. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008;133:440-9.

[PUBMED] |

| 2. | Proffit WR. Effects of orthodontic force on the maxilla and midface. In: Proffit WR, Fields HW Jr, editors. Contemporary orthodontics. 2 nd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1993. p. 281-4.

|

| 3. | Yüksel S, Uçem TT, Keykubat A. Early and late facemask therapy. Eur J Orthod 2001;23:559-68.

|

| 4. | Cha BK, Ngan PW. Skeletal anchorage for orthopedic correction of growing class III patients. Semin Orthod 2011;17:124-37.

|

| 5. | Kaya D, Kocadereli I, Kan B, Tasar F. Effects of facemask treatment anchored with miniplates after alternate rapid maxillary expansions and constrictions: A pilot study. Angle Orthod 2011;81:639-46.

[PUBMED] |

| 6. | Sar C, Arman-Ozcýrpýcý A, Uckan S, Yazýcý AC. Comparative evaluation of maxillary protraction with or without skeletal anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011;139:636-49.

|

| 7. | Major MP, Wong JK, Saltaji H, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Skeletal anchored maxillary protraction for midface deficiency in children and early adolescents with Class III malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J World Fed Orthod 2012;1:e47-54.

|

| 8. | Coscia G, Addabbo F, Peluso V, D'Ambrosio E. Use of intermaxillary forces in early treatment of maxillary deficient Class III patients: Results of a case series J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012;40:e350-4.

|

| 9. | Baccetti T, McGill JS, Franchi L, McNamara JA Jr, Tollaro I. Skeletal effects of early treatment of Class III malocclusion with maxillary expansion and face-mask therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:333-43.

[PUBMED] |

| 10. | Tanne K, Hiraga J, Kakiuchi K, Yamagata Y, Sakuda M. Biomechanical effect of anteriorly directed extraoral forces on the craniofacial complex: A study using the finite element method. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1989;95:200-7.

[PUBMED] |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3], [Figure 4], [Figure 5], [Figure 6], [Figure 7], [Figure 8], [Figure 9], [Figure 10]

[Table 1], [Table 2]

|