|

|

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

| Year : 2014 | Volume

: 2

| Issue : 3 | Page : 142-148 |

|

Class II division 1 malocclusions treated with fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator (FLMGM): The mechanism of sagittal occlusal correction

Osama Alali

Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Aleppo, Aleppo, Syria

| Date of Web Publication | 12-Sep-2014 |

Correspondence Address:

Osama Alali

Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Aleppo, Al-Shahbaa, P.O. Box: 10256, Aleppo

Syria

Source of Support: This work was supported by University of Damascus and University of Aleppo, Conflict of Interest: None  | Check |

DOI: 10.4103/2321-3825.140685

Clinical trial registration NCT01853995

Objectives: The objective of this study is to assess skeletal and dental changes contributing to sagittal correction of Class II malocclusion with fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator (FLMGM). Materials and Methods: A total of 38 patients with dental Class II division 1 malocclusion and retrognathic mandible comprised the study sample. All were in the pubertal growth spurt. While FLMGM was applied to the treatment group (n = 21, 13.2 years), no treatment was performed on the control group (n = 17, 12.5 years). Digital lateral cephalograms obtained at the beginning and end of treatment/observation period of 8 months were evaluated using sagittal occlusal analysis. Paired and independent t-tests were used to assess the differences within and between groups. Results: Fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator treatment resulted in the following significant changes: (1) Total mandibular length increased; (2) sagittal jaw relation enhanced due to chin advancement; (3) overjet reduced (4.06 mm) mainly as a result of skeletal mandibular advancement (83%) in combination with maxillary incisor retraction (17%); (4) Class II molar relation improved (5.56 mm) by a contribution of mandibular advancement (61%) and maxillary molar distalization (39%). Conclusions: Sagittal occlusal relationships efficiently improved by greater skeletal than dental changes. Stable horizontal position of lower molars and incisors was a benefit of FLMGM treatment. Keywords: Class II/1, fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator (FLMGM), sagittal correction

How to cite this article:

Alali O. Class II division 1 malocclusions treated with fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator (FLMGM): The mechanism of sagittal occlusal correction. J Orthod Res 2014;2:142-8 |

How to cite this URL:

Alali O. Class II division 1 malocclusions treated with fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator (FLMGM): The mechanism of sagittal occlusal correction. J Orthod Res [serial online] 2014 [cited 2018 Feb 15];2:142-8. Available from: http://www.jorthodr.org/text.asp?2014/2/3/142/140685 |

| Introduction | |  |

Targeting the mandible and trying to alter the amount and/or direction of its growth using functional appliances is the ideal approach to correct mandibular retrusion accompanying most Class II division 1 (Cl II/1) malocclusions. [1]

Fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator (FLMGM) is a novel Class II functional corrector. It represents the fixed version of removable double-plate appliance because the two appliances follow an identical mechanism of action, based on incorporated inclined plane in the mandible and guide bars in the maxilla. It was developed in an attempt to improve the effectiveness of removable double-plate appliance. [2]

The efficacy of FLMGM was reported in two case reports using data obtained from digital lateral cephalogram [2] and cone beam computed tomography. [3] Recently, the initial net skeletal and dentoalveolar effects of 8 months of FLMGM treatment were assessed in consecutively treated growing Cl II/1 patients. [4] The conclusions were that FLMGM was effective in stimulating mandibular growth and correcting skeletal Class II malocclusions and produced favorable dentofacial effects, with the matched untreated sample showing minimal changes. [2],[3],[4] The mechanism of sagittal correction of occlusion, overjet, and Class II molar relation, was not emphasized in that study.

The aim of the current controlled trial, therefore, was to identify the contribution of net skeletal and dental changes to sagittal correction of Cl II/1 malocclusion. The null hypothesis stated that there were no significant differences in dentoskeletal changes between FLMGM treated group and control untreated group.

| Materials and Methods | |  |

Subjects

The current study was prospective, controlled clinical trial with parallel groups. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee in the School of Dentistry, University of Damascus. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01853995.

A total of 43 adolescent Cl II/1 patients (25 treated, 18 untreated) referred to the Department of Orthodontics were enrolled in the original study sample. Selection criteria were:

- Cl II/1 malocclusion with an overjet >4 mm.

- Mild to moderate Class II Skeletal pattern (ANB >4° and A-pogonion (Pg) to maxillary plane <80°) with retrognathic mandible (SNB <76°).

- Growth potential. Only patients in the pubertal growth spurt peak, identified in hand-wrist radiographs, were invited.

Of these 43 patients, 38 completed this trial and comprised the final sample, and five were excluded [Table 1], all of them did not return for final records due to changing the area of residence. | Table 1: Study sample: Sex distribution, withdrawals and chronological age of the fi nal sample

Click here to view |

All subjects were followed on a parallel basis during a period of 8 months and the trial included all patients regardless of achievement of a normal occlusal relationship.

Patients and their parents gave prior informed consent to their inclusion in the investigation. In accordance with the other investigations studying fixed functional appliances, an observation period of 8 months was chosen. [5],[6],[7],[8] Treatment group patients (n = 21, mean age = 13.2 years) were treated using FLMGM without any form of orthodontic therapy, though the treatment was continued beyond this time point if the Class II malocclusion was not fully corrected and clinical objectives were not achieved. On the other hand, no orthodontic treatment was performed during that duration for the subjects of the control group (n = 17, mean age = 12.5 years), and most of the control subjects were offered suitable treatment at a later date.

The power analysis determined that, for a 5% significance level and a power of 80%, a sample size of 16 per group would be required to detect a difference of (+2 mm) between Class II treated and untreated groups. [9]

The Appliance

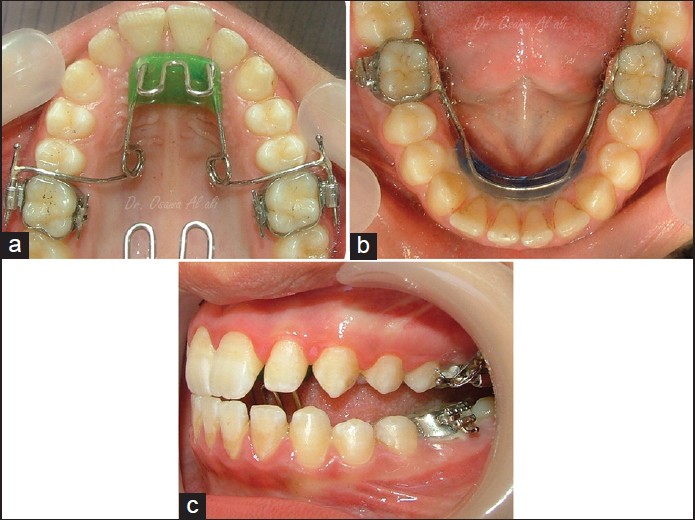

The FLMGM consists of two separate and fixed parts [Figure 1]a and b. The design was presented in the literature. [2],[4] A construction bite registration was taken with the incisors in an edge to edge relationship where achievable. | Figure 1: Fixed lingual mandibular growth modifi cator: (a) The maxillary part; (b) the mandibular part; (c) the patient occludes in the therapeutic anterior position (edge to edge)

Click here to view |

Within 2-week of the patient's initial records, all appliances were fitted by the same orthodontist [Figure 1]. After that, all treated patients were instructed to bite in the therapeutic anterior position [Figure 1]c and to keep their lips in touch as much as possible, and were seen at 6-week intervals until the end of treatment duration.

Analyses of Lateral Cephalograms

For each patient, a direct digital lateral cephalogram was taken pre- and post-treatment/observation, using PAX 400 (VATECH CO., Korea). All cephalograms were digitized on screen by a cursor-driven mouse and analyzed in a blind manner by the same orthodontist using commercial cephalometric software (Viewbox, version 3.1.1.13, dHAL Software, Kifissia, Hellas, Greece). All linear measurements were reduced to life size (radiographic enlargement of 7.54% in the median plane).

At the end of the treatment/observation period, sagittal occlusal analysis, according to the method of Pancherz [10] modified by Franchi et al. [11] was applied to assess sagittal occlusal changes and identify the mechanism of Class II correction. Moreover, the total mandibular length (Co-Gn) was measured. Cephalometric landmarks, lines, and measurements used are illustrated in [Figure 2] and presented in [Table 2]. | Figure 2: Sagittal occlusal analysis. In addition to traditional landmarks, two reference points were used: Frontomaxillary nasal suture (FMN); T point, most superior point of the anterior wall of sella turcica at the junction with tuberculum sellae. Registration line used: T-FMN L, line used for superimposition of two cephalograms with T point as the registration point. Reference coordination system (occlusal line [OL] and occlusal line perpendicular [OLp]): OL, a line through incisal tip of upper incisors and distobuccal cusp of upper permanent fi rst molars; OLp, a line perpendicular to OL through T point

Click here to view |

| Table 2: Pretreatment equivalence of the treatment group before fitting the appliance and the control group at the start of the examination period

Click here to view |

Statistical Analyses

Pretreatment equivalence and comparison of changes observed in the FLMGM and control groups were tested for significance with independent-sample t-test using SPSS, version 16.0. Changes occurring during the examination period in each group were tested with paired-sample t-test. P < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

To assess the method error, 20 cephalograms were picked at random from the treatment and control groups and redigitized and analyzed by the same orthodontist after an interval of 1 month, and the method error was calculated by Dahlberg's formula. The method error ranged between (0.19 and 0.58 mm) for the linear measurements of sagittal occlusal analysis. The method error for the total mandibular length was (0.39 mm).

| Results | |  |

Pretreatment Equivalence

Comparison of pretreatment data may assist in interpreting the results. At the beginning of the study, there were no significant differences between the test groups in all cephalometric measurements [Table 2].

Net Effects and Mechanism of Correction

Dentoskeletal effects are presented in [Table 3], and describe both the mean and standard deviation of cephalometric changes for each group and net FLMGM effects. The group differences for the different measurements are considered to represent the net effect of FLMGM treatment and would all be expected outcomes of functional therapy. | Table 3: Changes in the cephalometric variables at the end of the examination period, and net eff ects of FLMGM treatment

Click here to view |

In the FLMGM group, changes at the end of the examination period were statistically significant for all measurements except the sagittal position of maxillary base, upper incisor and lower dentition. In the control group, on the other hand, changes were not statistically significant except for two measurements, overjet and total mandibular length, which increased by (0.74 mm, P < 0.05) and (1.18 mm, P < 0.01), respectively.

In the maxilla, as net effects, the upper molars distalized by (2.39 mm, P < 0.001) and the upper incisors retracted by (0.88 mm, P < 0.01), [Table 3]. However, there was no statistically significant difference between FLMGM and control groups in sagittal position of maxilla A/occlusal line perpendicular (A/OLp).

In the mandible, there were great significant differences between FLMGM and control groups observed for the total mandibular length (Co-Gn) which increased by (2.33 mm, P < 0.001), and the bony chin (Pg/OLp) which moved forward an average of (3.44 mm, P < 0.001), [Table 3]. Unexpectedly, there were no statistically significant differences in the horizontal position of both the lower molar and incisor in FLMGM group compared with the control group.

Overall, the sagittal skeletal relation significantly enhanced; (A/OLp-Pg/OLp) decreased by (3.38 mm, P < 0.001). Dentally, there were a net overjet reduction of (4.06 mm, P < 0.001) and a net Class II molar correction of (5.56 mm, P < 0.001), [Table 3]. The relationship between net skeletal and dental changes contributing to Class II correction in the incisor and molar segments is seen in [Figure 3]. | Figure 3: Mechanism of Class II correction: maxillary and mandibular skeletal and dentoalveolar changes contributing to overjet and Class II molar relation correction

Click here to view |

Cephalometric changes in a Cl II/1 patient representative of FLMGM treatment group are shown in [Figure 4]. | Figure 4: A 13.4-year-old girl treated with fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator. (a) Before treatment; (b) treatment beginning; (c) after 8 months of orthopedic correction, sagittal occlusal relationships obviously improved and an acceptable posterior interdigitation was established

Click here to view |

| Discussion | |  |

The rate of discontinuation for FLMGM in this trial was 11.6%, and this figure compares favorably with reported rates of 27.7%, 15.8%, and 12.9%, for the Bass, [12] twin-block, [12] and Herbst [7] appliances, respectively. As long as there are drop-outs from clinical trials there is a natural increase in treatment effects. [13] To measure the true effectiveness of the treatment, an intention to treat analysis should be used. [14] In other words, the data analysis should include the results of treatment on all patients who initially entered the study, regardless of completion of the treatment. The data on patients who dropped-out of the current trial are not collected, as the patients failed to return at the end of the study period. For this reason, this approach was not performed.

It is well-known that in order to establish the effects of a functional appliance on growth, the best practical comparison must be undertaken with a concurrently enrolled group of untreated subjects having the same malocclusions as the treated patients. [15] A control group consisting of records obtained from untreated subjects exhibiting the same malocclusion as the treated patients was used in the present trial, and comparison of the starting forms showed an overall similarity of the FLMGM and control groups [Table 2].

The present trial, in agreement with the findings of other clinical studies using mandibular anterior repositioning appliance (MARA), functional mandibular advancer (FMA) and twin-block, [16] were not able to find evidence for headgear effect on the anterior growth of the maxilla. The maxillary part of FLMGM does not convert the entire maxilla into a rigid unit to which heavy functional forces are applied during bite correction [Figure 1]a. The functional load mostly transmitted to the upper molar was responsible for significant distal movement of the upper molars, which aids the correction of the distoocclusion. This distalization is an expected outcome of functional therapy and confirm previous observations on Herbst appliance, [11],[17] Jasper Jumper and many other intermaxillary functional appliances. [1]

In positioning the mandible forward, FLMGM successfully enhanced the growth potential of the mandible in Class II adolescent patients. The variables measuring skeletal mandibular growth and position were significantly changed. In principle, the clinical significance of a recorded increase in mandibular length needs to be considered in terms of forward chin positioning. [18] The net increase in total mandibular length seen in the present trial was statistically significant and associated with a significant advancement of the bony chin. These outcomes are in agreement with the findings of previous clinical studies using the MARA, [5] FMA, [6] twin-block, [12] and removable double-plate system, [19],[20],[21],[22] but contradict the findings of studies of Lund and Sandler, [16] and McNamara et al. [23] where functional treatment led to an increase in the mandible length with no significant advancement of the chin.

Increasing of total mandibular length is a natural result of a growing child. Hence, authors shouldn't say that FLMGM appliance growth the mandible.

The sagittal jaw relation is obviously enhanced thus the severity of Class II skeletal pattern is effectively reduced. This effect of FLMGM, and other functional appliances such as MARA [5] and twin-block, [16] is not the result of an inhibition effect on the maxilla but of the pronounced forward growth stimulation of the mandible. In contrast, removable double-plate system achieves the sagittal treatment goal through its almost exclusive effect upon the maxilla with relatively limited influence on the mandibular position. [20],[21]

The correction of the Cl II/1 malocclusion produced by functional appliances was due largely to a combination of some skeletal, but mainly dentoalveolar changes. [6],[7],[12],[17] For instance, Ruf and Pancherz found that approximately 31% of the overjet correction was achieved by lingual movement of the upper incisors, and 42% by lower incisors flaring. [17] According to literature review, functional appliances, [1],[11],[16] in general, frequently cause lower incisors flaring, and this effect is usually considered unfavorable and should be limited as it reduces the potential for orthopedic change. [24]

In the current trial, which was started during the peak of pubertal growth spurt, overjet reduction was mainly a result of a significant skeletal mandibular advancement (83%) in combination with maxillary incisor retraction (17%), and molar correction was largely accomplished by a mandibular advancement (61%) and distal movement of the maxillary molars (39%).

It has been reported that the level of skeletal maturation influences the outcome of dentofacial orthopedic treatment, and the pubertal growth spurt is the most suitable period for growth modification to achieve pronounced skeletal effect. [9] Timing of the FLMGM therapy, therefore, played a crucial role, causing more skeletal contribution to occlusal correction. On the other hand, the lesser amount of dentoalveolar contribution is due to the small and insignificant effect of FLMGM on the position of lower dentition, which is considered quite surprising.

By considering the design of FLMGM, it is possible to explain why the sagittal position of the lower incisors and molars remained virtually unchanged. The mandibular part of FLMGM contains a skeletally anchored anterior acrylic pad with no contact with lower anterior teeth. Thus, there is no force acting on the lower dentition causing mesial tooth movements. Likewise, a negligible change in the position of the lower teeth has been reported by Cura et al. [25] using Bass appliance and Sander and Lassak using the double-plate appliance. [19] Hence, one can conclude that initial lower incisor protrusion may no longer be a contraindication to FLMGM treatment as with Herbst and other intermaxillary functional appliances. [8]

Retraction of the upper incisor is a common effect of functional treatment. [1],[11],[16] In the present trial, it can be attributed to the mechanism of "muscular equilibrium breaking." [4] While the vertical advancement loops work as a shield relieving the tongue pressure on the incisors, only lingually-directed functional forces generated by the sealed lips affect the incisors and cause this effect. In the literature, removable or fixed appliances with palatal crib, which eliminate the tongue/incisors contact, produced significant decreases in resting tongue pressures on the incisors, and lingual axial inclination. [26]

Long-term stability of achieved occlusion seems mainly to depend on a stable cuspal interdigitation. [27] In the present trial, from a clinical perspective, the lateral open bite was mild at the end of the functional appliance phase [Figure 4], unlike other functional appliances such as Dynamax and twin-block appliance. [28] However, it must be stressed that the present trial reported only short-term effects and no conclusions can be drawn about long-term stability. Therefore, further studies maybe performed to establish long-term stability of treatment. Additional assessment is also suggested on what role, if any, adaptation and/or relocation in the temporomandibular joint play in the achieved sagittal occlusal correction.

| Conclusions | |  |

- FLMGM effects were mostly skeletal in nature and are due to increase in total mandibular length and forward repositioning of the chin.

- FLMGM appeared to be advantageous in terms of positional stability of lower incisors and molars.

- The distal movement of upper molars and the retraction of upper incisors were an important component of molar relationship and overjet corrections, respectively.

| Acknowledgment | |  |

The author thanks the patients for taking part in this study. The author is grateful to Dr. Nadia Abdul Rahman for her assistance in the paper preparation.

| References | |  |

| 1. | Karacay S, Akin E, Olmez H, Gurton AU, Sagdic D. Forsus Nitinol Flat Spring and Jasper Jumper corrections of Class II division 1 malocclusions. Angle Orthod 2006;76:666-72.

|

| 2. | Alali O. Fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator: A new appliance for class II correction. Dental Press J Orthod 2013;18:70-81.

|

| 3. | Alali O, Sawan N, Kaddah A, Khambay B. Fixed lingual mandibular growth modification appliance treatment: A 3-D analysis of the hard tissues changes. Int Poster J Dent Oral Med 2012;14:Poster 597.

|

| 4. | Alali O. A prospective controlled evaluation of Class II division 1 malocclusions treated with fixed lingual mandibular growth modificator. Angle Orthod 2014;84:527-533.

|

| 5. | Pangrazio-Kulbersh V, Berger JL, Chermak DS, Kaczynski R, Simon ES, Haerian A. Treatment effects of the mandibular anterior repositioning appliance on patients with Class II malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;123:286-95.

|

| 6. | Kinzinger G, Diedrich P. Skeletal effects in class II treatment with the functional mandibular advancer (FMA)? J Orofac Orthop 2005;66:469-90.

|

| 7. | O′Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, Sanjie Y, Mandall N, Chadwick S, et al. Effectiveness of treatment for Class II malocclusion with the Herbst or twin-block appliances: A randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;124:128-37.

|

| 8. | Papadopoulos MA. Orthodontic Treatment of the Class II Noncompliant Patient: current Principles and Techniques. Edinburgh, New York: Mosby; 2006.

|

| 9. | Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, De Toffol L, McNamara JA Jr. Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II malocclusion: A systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129:599.e1-12.

|

| 10. | Pancherz H. The mechanism of Class II correction in Herbst appliance treatment. A cephalometric investigation. Am J Orthod 1982;82:104-13.

[PUBMED] |

| 11. | Franchi L, Baccetti T, McNamara JA Jr. Treatment and posttreatment effects of acrylic splint Herbst appliance therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1999;115:429-38.

|

| 12. | Illing HM, Morris DO, Lee RT. A prospective evaluation of Bass, Bionator and Twin Block appliances. Part I - The hard tissues. Eur J Orthod 1998;20:501-16.

|

| 13. | Faber J. Intention-to-treat analysis and its application in orthodontics. J World Fed Orthod 2012;1:E45.

|

| 14. | O′Brien KD, Wright JL, Mandall NA. How to... do a randomized controlled trial. J Orthod 2003;30:337-41.

|

| 15. | Cura N, Saraç M. The effect of treatment with the Bass appliance on skeletal Class II malocclusions: A cephalometric investigation. Eur J Orthod 1997;19:691-702.

|

| 16. | Lund DI, Sandler PJ. The effects of Twin Blocks: A prospective controlled study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:104-10.

|

| 17. | Ruf S, Pancherz H. The herbst appliance: Research-based updated clinical possibilities. World J Orthod 2000;1:17-31.

|

| 18. | Collett AR. Current concepts on functional appliances and mandibular growth stimulation. Aust Dent J 2000;45:173-8.

[PUBMED] |

| 19. | Sander FG, Lassak C. The modification of growth with the jumping-the-bite plate compared to other functional orthodontic appliances. Fortschr Kieferorthop 1990;51:155-64.

|

| 20. | Lisson JA, Tränkmann J. Effects of angle Class II, division 1 treatment with jumping-the-bite appliances. A longitudinal study. J Orofac Orthop 2002;63:14-25.

|

| 21. | Lisson JA, Tränkmann J. Treatment begin and treatment effect in functional orthodontics with jumping-the-bite appliances. J Orofac Orthop 2003;64:341-51.

|

| 22. | Martina R, Cioffi I, Galeotti A, Tagliaferri R, Cimino R, Michelotti A, et al. Efficacy of the Sander bite-jumping appliance in growing patients with mandibular retrusion: A randomized controlled trial. Orthod Craniofac Res 2013;16:116-26.

|

| 23. | McNamara JA Jr, Bookstein FL, Shaughnessy TG. Skeletal and dental changes following functional regulator therapy on class II patients. Am J Orthod 1985;88:91-110.

[PUBMED] |

| 24. | Nanda R, Uribe FA. Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Elsevier; 2009.

|

| 25. | Cura N, Sarac M, Oztürk Y, Sürmeli N. Orthodontic and orthopedic effects of Activator, Activator-HG combination, and Bass appliances: A comparative study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996;110:36-45.

|

| 26. | Giuntini V, Franchi L, Baccetti T, Mucedero M, Cozza P. Dentoskeletal changes associated with fixed and removable appliances with a crib in open-bite patients in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008;133:77-80.

|

| 27. | Pancherz H. The effects, limitations, and long-term dentofacial adaptations to treatment with the herbst appliance. Semin Orthod 1997;3:232-43.

[PUBMED] |

| 28. | Thiruvenkatachari B, Sandler J, Murray A, Walsh T, O′Brien K. Comparison of Twin-block and Dynamax appliances for the treatment of Class II malocclusion in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010;138:144 e1-9; discussion 144-145.

|

[Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3], [Figure 4]

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3]

|