|

|

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

| Year : 2015 | Volume

: 3

| Issue : 1 | Page : 17-24 |

|

Jasper Jumper and activator-headgear combination: A comparative cephalometric study

Emine Kaygisiz, Tuba Tortop, Sema Yuksel, Selin Kale Varlik, Erdal Bozkaya

Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey

| Date of Web Publication | 29-Dec-2014 |

Correspondence Address:

Emine Kaygisiz

Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Gazi University, 8. Cad. 82. Sok No:4, Emek, Ankara 06510,

Turkey

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None  | Check |

DOI: 10.4103/2321-3825.146360

Aim: The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the skeletal and dentoalveolar effects of Jasper Jumper (JJ) and activator-headgear (AcHg) combinations and an untreated control group. Materials and Methods: The sample comprised 37 Class II high-angle patients. Twenty of them (mean age: 12.4 ± 0.61 years) were treated with JJ and 17 of them (mean age: 10.9 ± 0.74 years) were treated with AcHg. Mean treatment time was 5 months for the JJ group and 11 months for the AcHg group. Control group consisted of 20 Class II high angle patients (mean age: 10.4 ± 0.41 years) and mean observation period was 10 months. Results: Co-A showed significant increase in the JJ and control groups while SNA angle decreased significantly in only JJ group. Increase in SNB angle in AcHg group was significantly greater than in the JJ and control groups. In the JJ group, mandibular incisors protruded significantly. Conclusion: Both the AcHg and JJ treatments had restraining effect on maxillary growth, but stimulated significant mandibular growth. Anteroposterior discrepancy was corrected in the AcHg group mostly by the mandibular growth compared to JJ treatment. Maxillary incisors were retroclined in the AcHg group while mandibular incisors were proclined in the JJ group. Keywords: Activator, class II, functional, headgear, high angle, jasper jumper

How to cite this article:

Kaygisiz E, Tortop T, Yuksel S, Varlik SK, Bozkaya E. Jasper Jumper and activator-headgear combination: A comparative cephalometric study. J Orthod Res 2015;3:17-24 |

How to cite this URL:

Kaygisiz E, Tortop T, Yuksel S, Varlik SK, Bozkaya E. Jasper Jumper and activator-headgear combination: A comparative cephalometric study. J Orthod Res [serial online] 2015 [cited 2018 Sep 6];3:17-24. Available from: http://www.jorthodr.org/text.asp?2015/3/1/17/146360 |

| Introduction | |  |

Class II malocclusions are frequently observed in orthodontic practice, [1] and commonly treated with various removable or fixed functional appliances. [2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8] Most of the purely functional appliances by definition are within the removable category. Some of the most common are the Twin Block, Bionator, Activator, Frankel etc. [6] On the other hand, some of the commonly used fixed appliances are Jasper Jumper (JJ), Herbst, Twin Force Bite Corrector, Eureka Spring, MARA, etc. [9]

Functional appliances may be combined with extra-oral force applied to either the maxilla or the mandible. [7],[10],[11] The use of combined activator and high-pull headgear appliance has been recommended as a means of reducing vertical and sagittal maxillary displacement, [12],[13],[14],[15] achieving autorotation, increasing forward displacement of the mandible, [12],[13],[14] and improvement of the maxillomandibular relationship. [12],[15] Additionally, the vertical dental effect of the headgear-activator appliance is to restrain the eruption of the maxillary molars and incisors. [15] However, one major disadvantage is the need for patient compliance.

Jasper [2] developed a more flexible intraoral force module, JJ in 1987 to deal with a very issue of patient compliance. It has been observed that posterior forces to the maxillary dentition and reciprocal anterior forces to the mandibular dentition were applied. [2],[3],[4],[16]

Previous studies revealed that JJ appliance had a high-pull headgear effect on the maxilla. [4],[17],[18],[19] Weiland and Bantleon, [16] on the other hand, found that the JJ appliance had limited skeletal effect on the maxilla and stated that the change at point A might be due to a reflection of the retrusion of the upper incisors. Sari et al. [8] comparatively evaluated the use of removable JJ appliance-high-pull headgear with activator-headgear (AcHg) on high angle cases and showed that AcHg was more effective on the mandible, whereas JJ-occipital headgear was mainly effective on the maxilla. Additionally, they reported vertical skeletal relationship was worsened by the AcHg treatment. [8] Freeman et al. [20] also showed similar outcome with Sari et al. [8] and reported the bionator and high-pull face bow combination was not an effective treatment option in growing patients with increased vertical dimensions of the face.

Many studies might be found in the literature regarding the AcHg combination treatment, [7],[10],[15],[21] JJ with fixed appliances, [4],[16],[22] and removable JJ appliance with high-pull headgear. [8] Recently, JJ and AcHg combinations have been compared, however only the overall treatment effects including the fixed therapy were evaluated. [23] Additionally, a review of the literature revealed one study about the comparison of the initial dentoskeletal effects of JJ with fixed appliances, yet that study does not comprise a control group. [7] Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the initial skeletal and dentoalveolar effects of JJ and AcHg combinations with an untreated control group.

| Materials and Methods | |  |

A sample size of 15 patients/group, at α = 0.05, yields a statistical power very close to 0.80; in this study the sample size were increased to 57 patients.

Subjects for both study and control groups were collected retrospectively, from the patient list of Department of Orthodontics of the University; comprising 114 lateral cephalograms of 57 children with skeletal Class II high angle malocclusions (ANB ≥4°, SNB <80°, SN/GoGn ≥38°). The following criteria were used:

- Bilateral Class II molar relationship with at least half cusp distal molar relationship,

- Over jet equal or >4 mm,

- No tooth agenesis or missing permanent teeth,

- No craniofacial syndromes.

Two treatment groups and an untreated control group were evaluated for this study.

Group I, 20 subjects (8 males and 12 females) in the permanent dentition treated with JJ with fixed appliances (mean pretreatment chronological age: 12.4 ± 0.61 years). 0.018-inch slot brackets were used, and bands were placed with a transpalatal arch in the maxillary arch to increase stability. JJ was attached to the headgear tube of the first molars in the maxillary arch, and hooked to the mandibular arch wire over the mandibular canine bracket from the distal side with ball-pin attachments as prescribed by the manufacturer. JJs were selected according to the manufacturer's instructions. The patients were seen every 4 weeks, and the appliances were activated every 8 weeks. The average time that elapsed between insertion of the JJ and achievement of a Class I molar relationship was approximately 5 months.

Group II, 17 subjects (8 males and 9 females) (mean pretreatment chronological age: 10.9 ± 0.74 years) constituted the AcHg combination (AcHg) group. The AcHg appliance consisted of a bimaxillary block of acrylic, a maxillary labial bow, and Adams clasps on the maxillary first molars. The incisal third of the mandibular incisors was covered with acrylic. The headgear tubes were applied to premolar regions. The construction bite was taken with the mandible protruded in an edge-to-edge incisor relationship. The occlusal surfaces of the mandibular posterior teeth were relieved from the acrylic. The outer bow was tilted 15° upward from the occlusal plane, exerting 350 g of force in each side. The patients were instructed to wear the appliances about 14 h a day.

Class I molar relationship was achieved in 11 months.

Group III, 20 subjects (7 males and 13 females) (mean initial chronological age: 10.4 ± 0.41 years) constituted the control group. Mean observation period of the control group was 10 months.

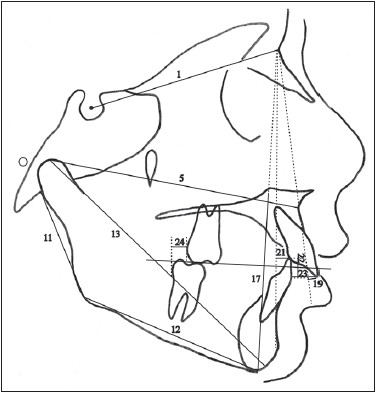

Skeletal and dentoalveolar changes were evaluated by means of 11 linear and 15 angular measurements on standardized lateral cephalograms taken at the beginning and after achievement of a Class I molar relationship in the both study groups. Same measurements were made on lateral cephalograms taken at the beginning and end of the observation period in the control group [Figure 1] and [Figure 2]. | Figure 1: Linear cephalometric measurements used in this study. 1. S-N distance; 5. Co-A distance; 11. Go-Ar distance; 12. Go-Me distance; 13. Co-Gn distance; 15. CoGn-CoA difference (maxillomandibular diff.); 17. ANS-Me distance; 19. U1-NA distance; 21. L1-NB distance; 22. Overbite; 23. Overjet; 24. Molar relationship

Click here to view |

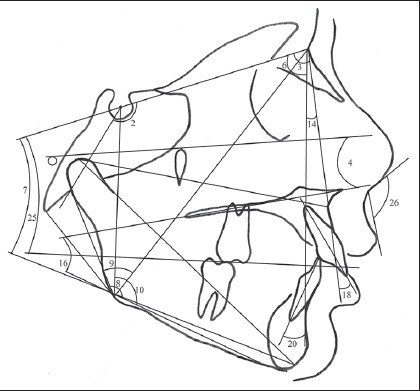

| Figure 2: Angular cephalometric measurements used in this study. 2. Saddle angle; 3. SNA angle; 4. FH/palatal plane angle; 6. SNB angle; 7. SN/GoGn angle; 8. GnGoAr angle; 9. NGoAr angle; 10. MeGoS angle; 14. ANB angle; 16. PP/MP angle; 18. U1/NA angle; 20. L1/NB angle; 25. SN/occlusal plane angle; 26. Nasolabial angle

Click here to view |

Ten randomly selected cephalograms from each group were retracted and 2 weeks after the first tracing was used to determine the method error.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done with SPSS for Windows version 16.0 package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

To check data normality the Shapiro-Wilk test was applied. Differences between the groups were determined by ANOVA and the Tukey test. Chi-square tests were used to check the compatibility among the three groups regarding severity of the initial Class II molar relationship. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate the treatment effects and changes during the observation period in each group. Significance level was set at P < 0.05.

| Results | |  |

Method error coefficients of all measurements were calculated and found to be within acceptable limits (range: 0.98-1.00).

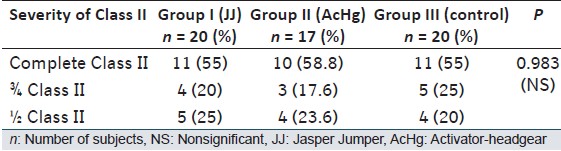

Initial severity of Class II molar relationship was similar between the groups [Table 1]. | Table 1: Comparison of initial severity of the Class II molar relationship between the groups

Click here to view |

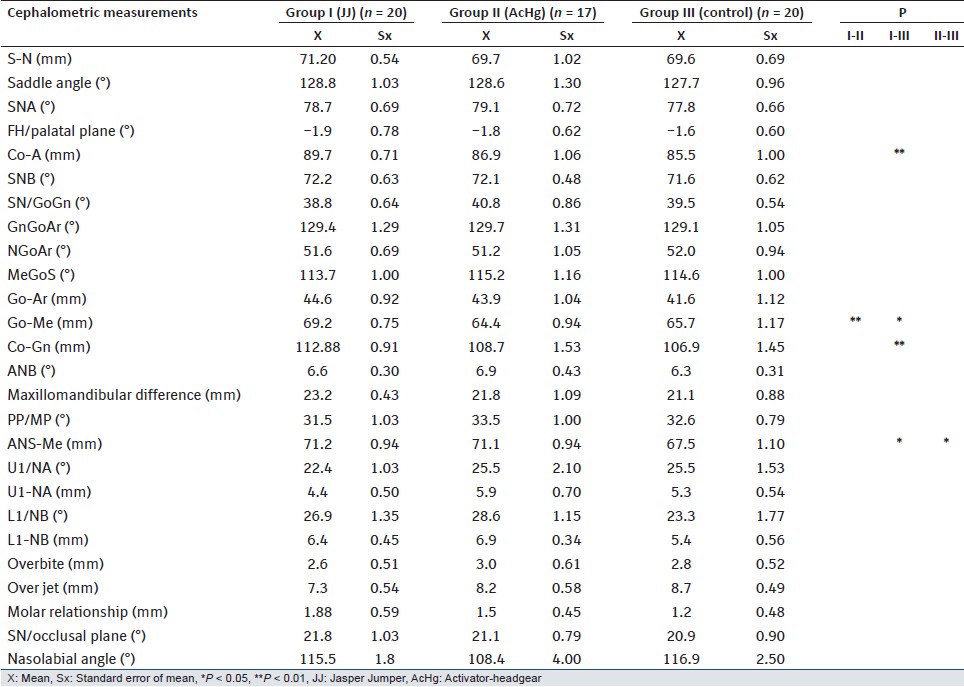

Statistical comparison of the pretreatment values showed Co-A, Co-Gn, Go-Me, ANS-Me measurements were significantly greater in JJ group than in the control group. Pretreatment value of Go-Me was significantly greater in JJ group than in AcHg group. Between the AcHg and control group, the significant differences were observed in the pretreatment values of ANS-Me [Table 2]. | Table 2: Pretreatment mean values and statistical differences between groups

Click here to view |

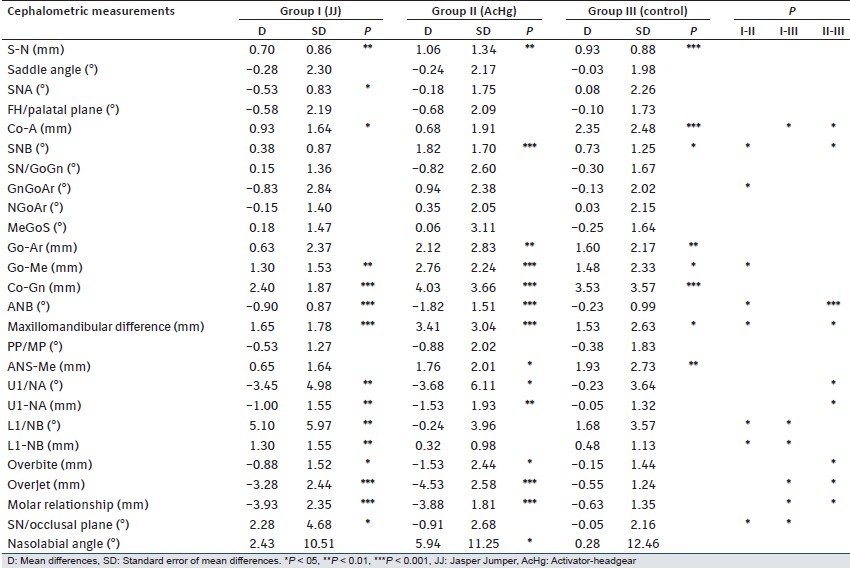

[Table 3] presents treatment changes of JJ and AcHg groups and observation changes of the control group and the comparison among the groups.

In the maxilla, Co-A showed a significant increase in the JJ and control groups while SNA angle decreased significantly in only JJ group.

In the mandible, there were significant increases in SNB and Go-Ar in AcHg and control groups. Go-Me and Co-Gn dimensions showed significant increases in all groups. | Table 3: Treatment changes of JJ and AcHg groups, observation period changes of control group and comparison among groups

Click here to view |

Evaluation of the maxillomandibular relationships showed that the decrease in ANB angle and increase in maxillomandibular difference were statistically significant in both treatment groups. In the control group, only the increase in maxillomandibular difference was found to be significant.

There were significant palatal tipping (U1/NAdg) and retrusion (U1-NAmm) of maxillary incisors in both treatment groups. In the mandibular dentition, labial tipping (L1/NBdg) and protrusion (L1-NBmm) of mandibular incisors were significant only in the JJ group. SN/occlusal plane angle showed a significant difference in the JJ group. Over jet and overbite were reduced significantly in the treatment groups. Furthermore, a significant decrease in molar relationship was found in both treatment groups.

Comparison Among Groups

In the maxillary variables, only Co-A had a statistical difference between treatment and control groups.

In the mandible, increase in SNB angle in AcHg group was significantly greater than in the JJ and control groups. Increments in corpus length (Go-Me) showed statistically significant difference between the treatment groups. Decrease in GnGoAr angle in the JJ group was significantly different compared to an increase in AcHg group.

Changes in ANB angle and maxillomandibular difference in AcHg group was found to be significantly different compared to the JJ and control groups.

In the maxillary dentition, palatal tipping (U1/NAdg) and retrusion (U1-NAmm) of maxillary incisors showed significant difference between AcHg and control groups. Labial tipping (L1/NBdg) and protrusion (L1-NBmm) of mandibular incisors in JJ group was significantly different compared to AcHg and control groups. Decrease in overbite was significantly greater in AcHg group than in control group. Correction of molar relation and overjet in treatment groups showed significant difference compared to control group. Increase in SN/occlusal plane angle in the JJ group was significantly different compared to other groups.

| Discussion | |  |

Patient compliance is one of the most important factors influencing the choice of appliance during orthodontic treatment. In this study, the JJ treatment without depending on patient compliance was compared with the AcHg treatment in which patients' compliance is essential. Both treatment groups were successfully treated to Class I molar relationship with JJ and AcHg.

The treatment and control groups had similar conditions for the initial severity of the Class II molar relationships in this study. Compatibility of the groups regarding initial severity of the Class II molar relationship was essential because correction of a Class II malocclusion is related to the initial severity of the anteroposterior discrepancy. [24]

The JJ group had a short treatment time according to AcHg treatment time and observation period. In some studies [25],[26] the differences in treatment times were solved by annualization. However, in this study, treatment and observation periods were limited to in months. Hence, it has been thought that the annualization might not be meaningful.

The mean age of JJ group was greater than the mean age of the control group. As the mean age of JJ group was around 12 years, due to ethical purposes it was not possible to find a control group. There was a difference in chronological age between JJ and AcHg groups. AcHg can be applied during the mixed dentition. However, JJ appliance needs to be applied on fixed appliances, so the patients were in a permanent dentition.

The norm values of these linear parameters were not identical for different age groups. [27],[28] Hence, the difference in the pretreatment values between the groups could be interpreted as an effect of the difference in age.

In the JJ group, a significant increase in maxillary sagittal growth (Co-A) was observed, but increase was significantly less than the control group which indicated a restriction in the maxillary sagittal growth. This result was controversial to that of a study which reported JJ had a minimal or no effect on maxillary prognathism, [3] however, in numerous other studies JJ was reported to have a restraining effect on maxilla. [4],[7],[16],[18],[19],[22],[29],[30],[31] Furthermore, significantly less increase according to the control group in the Co-A distance in AcHg group indicated a restriction in the maxillary sagittal growth. Some other studies also reported similar results about the restriction of the maxilla by AcHg treatment. [5],[10],[11],[31],[32]

Increase in SNB angle in AcHg group was significantly greater than in the JJ and control groups. Though, mandibular sagittal linear measurements increased in all groups, the Go-Me measurement, representing mandibular corpus length, increased in AcHg group more than the JJ group. In AcHg group increase in SNB, angle was in accordance with the results of previous studies. [5],[7],[11] Effect of JJ on mandibular growth has also been similar with several studies [4],[18],[19] who did not find any significant effect on mandibular growth after JJ treatment. Conversely, in numerous other JJ studies increase in SNB angle was reported. [3],[7],[16],[29]

Changes in ANB angle and maxillomandibular difference in AcHg group was found to be significantly different compared to the JJ and control groups. Actually, sagittal relationship was improved in both treatment groups, so it could be commented that main difference observed between JJ and AcHg groups was in their effect on the sagittal positions of maxilla and mandible. In the AcHg group, ANB reduction was achieved mostly through the mandibular, but also maxillary changes. It has been reported previously that AcHg combination stimulates mandibular growth, increases mandibular length, [5],[7],[20],[31],[33],[34] and has a restrictive effect on maxillary sagittal growth. [5],[10],[20],[31],[35] However, in the JJ group, ANB reduction was achieved by maxillary restriction and dentoalveolar changes. Mills and McCulloch, [17] and Kόηόkkeles et al. [22] also showed that the appliance produced mostly dentoalveolar changes.

In hyperdivergent Class II patients, reducing or at least not increasing the vertical dimension should be aimed during orthodontic treatment. In this study, JJ treatment caused no significant change in any of the measurements related with the vertical dimension. Yet, in the AcHg and control groups, only ANS-Me measurement, representing lower facial height, increased significantly but there was no significant difference between the groups. In contrast to the present study, Cura et al. [5] reported significant increases in all vertical measurements after AcHg treatment, but, if their data were carefully evaluated it could be noticed that, although there were 2-2.5 mm increases in the linear measurements, there were slight decreases in the mean values of NSL/ML and NSL/NL angles after treatment. Increases in linear measurements were due to the vertical growth as no difference was found compared to control group in this study. It should be noticed that no control group was used in Cura et al.'s study. [5] Sari et al. [8] found no significant maxillary or mandibular rotation in Class II subjects with increased vertical dimension after AcHg treatment, but they reported some increase in N-Me and N-ANS measurements similar to the present study. Some other studies also reported similar results about the effect of AcHg on vertical dimension. [34],[35] Karacay et al. [29] reported significant posterior mandibular rotation and increase in the vertical dimension after JJ treatment. However, the results of other studies which reported no increase in mandibular rotation or linear vertical dimensions after JJ treatment were in accordance with the results of the present study. [3],[7],[19],[22],[30]

Decrease in GnGoAr angle in the JJ group was significantly different compared to an increase in AcHg group. As the gonial region might be a key point for vertical growth; this could be a discriminant factor for these treatment protocols. However, this still needs long-term evaluations.

Main difference observed between JJ and AcHg groups was in their effect on the sagittal positions of incisors. In the maxillary dentition, retrusion of maxillary incisors showed significant difference between AcHg and control groups. Protrusion of mandibular incisors in JJ group was significantly different compared to AcHg and control groups. This unfavorable effect of JJ appliance was consistent with the previous studies. [4],[5],[7],[8],[10],[11],[17],[18],[22],[30] Nalbantgil et al. [19] used sectional arches for preventing or minimizing the increased inclination of the lower incisors in the JJ appliance, but they also found a significant proclination. Although labial tipping of the mandibular incisors in patients treated with an AcHg has been reported previously, [11],[35] Lima et al. [23] showed that these teeth remained in their original position at the end of the fixed appliance therapy. Effect of AcHg on the maxillary incisors was also in agreement with the other studies. [8],[15],[34],[36]

The overbite decreased in both treatment groups significantly, but decrease in overbite was significantly greater in the AcHg group than in the control group. It was consistent with the other studies. [31],[34]

Correction in over jet and molar relationship was similar between the JJ and AcHg groups, but was significantly different compared to the control group. Improvements of the molar relationship and over jet seemed to be a combination of the maxillary and mandibular skeletal and dentoalveolar changes. Weiland et al. [7] reported that JJ and AcHg appliances had similar growth restricting effect on maxilla, and they concluded that the percentages of skeletal changes that accounted for the over jet and overbite correction were higher in the JJ group.

Increase in SN/occlusal plane angle in the JJ group was significantly different compared to other groups which can be explained by the result of dentoalveolar changes rather than a skeletal effect. Retrusion of upper incisors, protrusion of lower incisors point to a clockwise rotation of the occlusal plane. This result of the present study was in agreement with those of previous studies which compared the JJ and control groups. [19],[29] Some studies of AcHg reporting nonsignificant changes in the SN/occlusal plane angle were in agreement with this study. [1],[10]

| Conclusion | |  |

- Both the AcHg and JJ treatments had restraining effect on maxillary growth, but stimulated significant mandibular growth. Antero-posterior discrepancy was corrected in the AcHg group mostly by the mandibular growth compared to JJ treatment.

- Vertical dimensions remained unchanged in both treatment groups.

- Maxillary incisors were retroclined in the AcHg group while mandibular incisors were proclined in the JJ group.

Due to mandibular skeletal changes using AcHg seemed to be a better choice in the treatment of hyperdivergent Class II malocclusion, but with its satisfying results JJ could be an alternative approach for noncompliant adolescent patients.

| References | |  |

| 1. | Ingervall B. Prevalence of dental and occlusal anomalies in Swedish conscripts. Acta Odontol Scand 1974;32:83-92.  [ PUBMED] |

| 2. | Jasper JJ. The Jasper Jumper - A Fixed Functional Appliance. Sheboygan, Wis: American Orthodontics; 1987. p. 5-27.  |

| 3. | Stucki N, Ingervall B. The use of the Jasper Jumper for the correction of class II malocclusion in the young permanent dentition. Eur J Orthod 1998;20:271-81.  |

| 4. | Cope JB, Buschang PH, Cope DD, Parker J, Blackwood HO 3 rd . Quantitative evaluation of craniofacial changes with Jasper Jumper therapy. Angle Orthod 1994;64:113-22.  |

| 5. | Cura N, Sarac M, Oztürk Y, Sürmeli N. Orthodontic and orthopedic effects of activator, activator-HG combination, and Bass appliances: A comparative study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996;110:36-45.  |

| 6. | Graber TM, Rakosi T, Petrovic AG. Dentofacial Orthopedics with Functional Appliances. 2 nd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1997. p. 346-52.  |

| 7. | Weiland FJ, Ingervall B, Bantleon HP, Droacht H. Initial effects of treatment of class II malocclusion with the Herren activator, activator-headgear combination, and Jasper Jumper. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1997;112:19-27.  |

| 8. | Sari Z, Goyenc Y, Doruk C, Usumez S. Comparative evaluation of a new removable Jasper Jumper functional appliance vs an activator-headgear combination. Angle Orthod 2003;73:286-93.  |

| 9. | Uribe F, Rothenberg J, Nanda R. The twin force bite corrector in the correction of the class II malocclusion in adolescent patients. In: Papadopoulos MA, editor. Orthodontic Treatment of the Class II Noncompliant Patient. St Louis: Mosby; 2006. p. 181-202.  |

| 10. | Lagerström LO, Nielsen IL, Lee R, Isaacson RJ. Dental and skeletal contributions to occlusal correction in patients treated with the high-pull headgear-activator combination. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1990;97:495-504.  |

| 11. | Dermaut LR, van den Eynde F, de Pauw G. Skeletal and dento-alveolar changes as a result of headgear activator therapy related to different vertical growth patterns. Eur J Orthod 1992;14:140-6.  |

| 12. | Teuscher U. A growth-related concept for skeletal class II treatment. Am J Orthod 1978;74:258-75.  [ PUBMED] |

| 13. | Stöckli PW, Teuscher U. Combined activator headgear orthopedics. In: Graber TM, Swain B, editors. Current Orthodontic Principles and Techniques. St Louis: Mosby; 1985. p. 405-83.  |

| 14. | Teuscher U. Appraisal of growth and reaction to extraoral anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1986;89:113-21.  |

| 15. | Bendeus M, Hägg U, Rabie B. Growth and treatment changes in patients treated with a headgear-activator appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2002;121:376-84.  |

| 16. | Weiland FJ, Bantleon HP. Treatment of class II malocclusions with the Jasper Jumper appliance - A preliminary report. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1995;108:341-50.  |

| 17. | Mills CM, McCulloch KJ. Case report: Modified use of the Jasper Jumper appliance in a skeletal class II mixed dentition case requiring palatal expansion. Angle Orthod 1997;67:277-82.  |

| 18. | Covell DA Jr, Trammell DW, Boero RP, West R. A cephalometric study of class II division 1 malocclusions treated with the Jasper Jumper appliance. Angle Orthod 1999;69:311-20.  |

| 19. | Nalbantgil D, Arun T, Sayinsu K, Fulya I. Skeletal, dental and soft-tissue changes induced by the Jasper Jumper appliance in late adolescence. Angle Orthod 2005;75:426-36.  |

| 20. | Freeman CS, McNamara JA Jr, Baccetti T, Franchi L, Graff TW. Treatment effects of the bionator and high-pull facebow combination followed by fixed appliances in patients with increased vertical dimensions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007;131:184-95.  |

| 21. | Ulusoy C, Darendeliler N. Effects of class II activator and class II activator high-pull headgear combination on the mandible: A 3-dimensional finite element stress analysis study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008;133:490.e9-15.  |

| 22. | Küçükkeles N, Ilhan I, Orgun IA. Treatment efficiency in skeletal class II patients treated with the jasper jumper. Angle Orthod 2007;77:449-56.  |

| 23. | Lima KJ, Henriques JF, Janson G, Pereira SC, Neves LS, Cançado RH. Dentoskeletal changes induced by the Jasper jumper and the activator-headgear combination appliances followed by fixed orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013;143:684-94.  |

| 24. | Janson G, Valarelli FP, Cançado RH, de Freitas MR, Pinzan A. Relationship between malocclusion severity and treatment success rate in Class II nonextraction therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009;135:274.e1-8.  |

| 25. | Angelieri F, de Almeida RR, Janson G, Castanha Henriques JF, Pinzan A. Comparison of the effects produced by headgear and pendulum appliances followed by fixed orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod 2008;30:572-9.  |

| 26. | Driscoll-Gilliland J, Buschang PH, Behrents RG. An evaluation of growth and stability in untreated and treated subjects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001;120:588-97.  |

| 27. | Riolo ML, Moyers RE, McNamara JA, Hunter WS. An atlas of craniofacial growth. In: Craniofacial Growth Series. Monograph No. 2. Ann Arbor: Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan; 1974.  |

| 28. | McNamara JA, Brudon WL. Orthodontic and Orthopedic Treatment in Mixed Dentition. Ann Arbor: Needham Press; 1993.  |

| 29. | Karacay S, Akin E, Olmez H, Gurton AU, Sagdic D. Forsus Nitinol Flat spring and Jasper Jumper corrections of class II division 1 malocclusions. Angle Orthod 2006;76:666-72.  |

| 30. | Herrera FS, Henriques JF, Janson G, Francisconi MF, de Freitas KM. Cephalometric evaluation in different phases of Jasper jumper therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011;140:e77-84.  |

| 31. | Janson G, Caffer Dde C, Henriques JF, de Freitas MR, Neves LS. Stability of class II, division 1 treatment with the headgear-activator combination followed by the edgewise appliance. Angle Orthod 2004;74:594-604.  |

| 32. | Marsan G. Effects of activator and high-pull headgear combination therapy: Skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft tissue profile changes. Eur J Orthod 2007;29:140-8.  |

| 33. | O'Reilly MT, Yanniello GJ. Mandibular growth changes and maturation of cervical vertebrae - A longitudinal cephalometric study. Angle Orthod 1988;58:179-84.  |

| 34. | Türkkahraman H, Sayin MO. Effects of activator and activator headgear treatment: Comparison with untreated class II subjects. Eur J Orthod 2006;28:27-34.  |

| 35. | Oztürk Y, Tankuter N. Class II: A comparison of activator and activator headgear combination appliances. Eur J Orthod 1994;16:149-57.  |

| 36. | Lerstøl M, Torget O, Vandevska-Radunovic V. Long-term stability of dentoalveolar and skeletal changes after activator-headgear treatment. Eur J Orthod 2010;32:28-35.  |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2]

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3]

|