| |

|

| Year : 2012 | Volume

: 6

| Issue : 1 | Page : 19-22 |

|

|

|

|

|

CASE REPORT Myositis ossificans circumscripta of the triceps due to overuse in a female swimmer

Saartje Defoort, NA Arnout, PD Debeer

Department of Musculoskeletal Science, Division of Orthopedics, Pellenberg, Leuven, Belgium

Correspondence Address:

Saartje Defoort

SJKI Izegem, Roeselaarsestraat 47, 8870 Izegem

Belgium

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None  | 2 |

DOI: 10.4103/0973-6042.94315

|

|

|

|

| Date of Web Publication | 26-Mar-2012 |

Abstract Abstract | | |

Myositis ossificans is a rare condition characterized by non-neoplastic heterotopic bone formation in soft tissue and skeletal muscle. It is a benign and often self-limiting disease with no need for surgery. Here, we describe a young female swimmer with myositis ossificans circumscripta of the triceps due to overuse. Because of the benign character of the lesion, conservative treatment was initiated with rest and anti-inflammatory drugs. She obtained complete resolution after 6 months and was able to return to normal sporting activities. Myositis ossificans circumscripta is a rare benign lesion with an excellent prognosis. Most lesions in athletes occur due to contusions or strains; however, overuse is now described as well. Spontaneous resolution is seen in almost all cases. Cases in which, despite conservative treatment, a painful mass persists, surgical excision can be considered.

Keywords: Myositis ossificans circumscripta, overuse, soft tissue tumor, triceps

How to cite this article:

Defoort S, Arnout N A, Debeer P D. Myositis ossificans circumscripta of the triceps due to overuse in a female swimmer. Int J Shoulder Surg 2012;6:19-22 |

Introduction Introduction | |  |

Myositis ossificans (MO) is a rare condition characterized by non-neoplastic heterotopic bone formation in soft tissue and skeletal muscle. It is a benign and often self-limiting disease.

This condition is most likely to occur after previous trauma. In athletes, it occurs mainly due to contact injuries which cause contusions, bruises and strains, or overuse due to intensive training.

In this article, we describe a 32-year-old swimmer, who developed MO due to overuse during an intensive swimming program.

Case Report Case Report | |  |

A 32-year-old woman was referred by a general practitioner to our center, with progressive onset of pain in the left upper arm over the past 2 weeks. He suspected a muscle rupture; however, no specific onset of pain could be remembered. She was involved in an intensive crawl swimming training program. She trained approximately 6 days per week for more than 10 hours during the last 3 months. She experienced some fatigue; however, she never experienced any sprain injury or trauma to the upper extremities. She had a blank medical history.

Clinical examination at the time of presentation showed a well-defined small nodule on the posteromedial part of the triceps. Strength and mobility of shoulder and elbow were normal. She had full active and passive range of motion in elbow and shoulder. However, deep flexion in the elbow and forced anteflexion of the shoulder were painful. Further examination of vascular and neurological structures was completely normal.

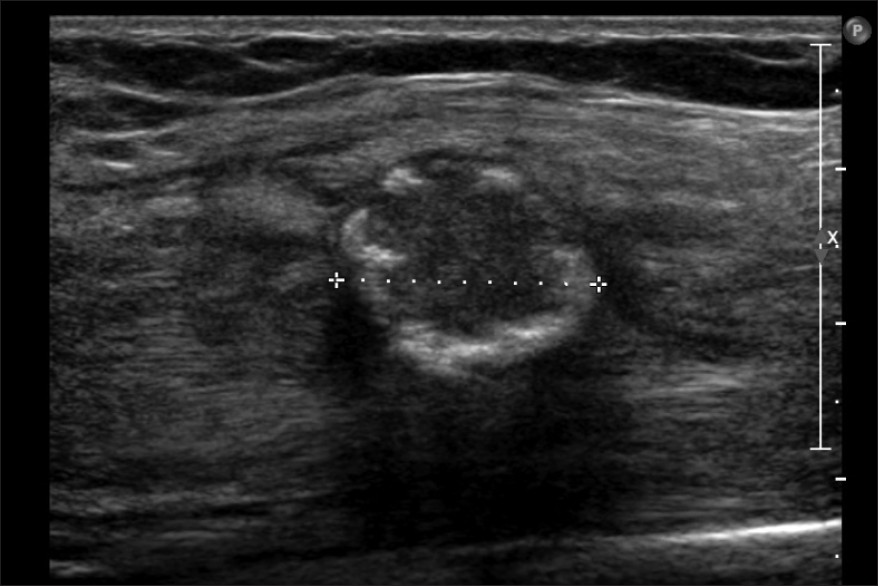

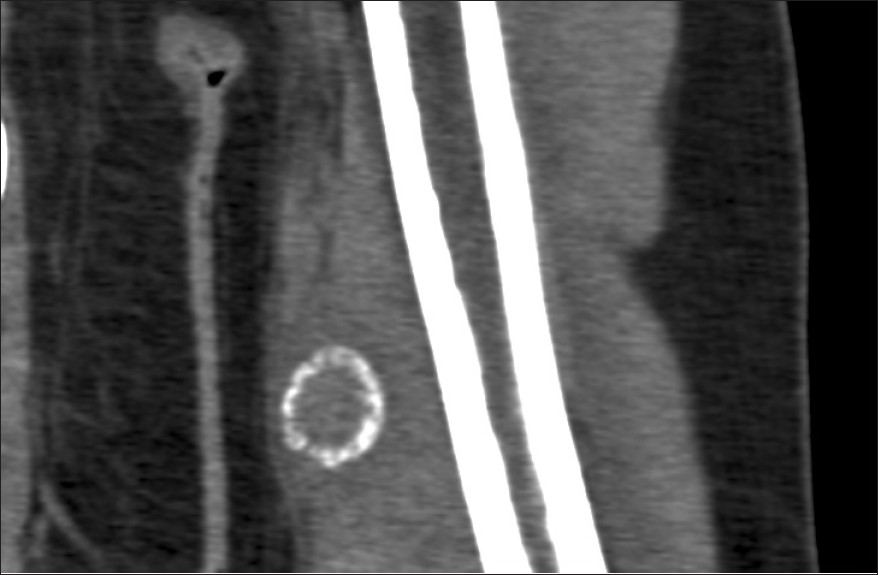

Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs [Figure 1] showed sharply demarcated lesion, with partially mineralized zones in the periphery, located in the posteromedial soft tissues of the upper arm. Ultrasound [Figure 2] confirmed the peripheral calcified lesion in the medial head of the triceps. The diameter of the lesion was 1.7 cm and it was surrounded by edema. All these aspects were compatible with an active phase of myositis ossificans circumscripta (MOC). A computed tomography scan [Figure 3] confirmed the tentative diagnosis of MOC because of the presence of peripheral mineralization and perilesional edema. | Figure 1: Anteroposterior and lateral X-ray at first presentation showing that the lesion is located posteromedially of the midshaft of the upper arm. The lesion is characterized by a sharply demarcated and partially mineralized periphery

Click here to view |

| Figure 2: Initial ultrasound confirmed the peripheral calcification of the lesion in the medial caput of the triceps. The diameter of the lesion was 1.7 cm

Click here to view |

| Figure 3: Computed tomography of the lesion showed the characteristic peripheral calcification of the lesion. There are no cortical or bone marrow abnormalities

Click here to view |

Outcome

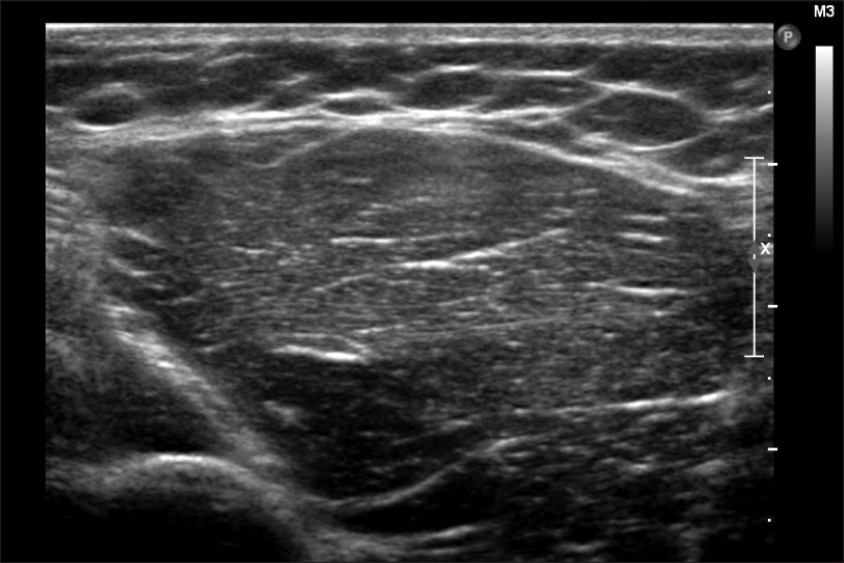

The patient was treated conservatively with rest and anti-inflammatory drugs. Clinical follow-up showed progressive pain relief. However, a hard, palpable and tender mass persisted for 2 months. Control radiographs [Figure 4] and ultrasound [Figure 5] demonstrated a more sclerotic lesion after 2 months, which gradually disappeared after 6 months. She was allowed to restart her sport activities at her own pace. | Figure 4: X-ray of the lesion 1 year after diagnosis and conservative treatment, showing complete resolution

Click here to view |

| Figure 5: Ultrasound of the lesion 1 year after diagnosis and conservative treatment, showing complete resolution

Click here to view |

One year later, recovery was complete with resolution of the lesion and a normal pain-free mobility of the shoulder and elbow.

Discussion Discussion | |  |

MO can be classified into three types using the classification of Noble: [1] 1) Myositis ossificans progressiva or fibrodysplasia progressiva (FOP) is a severe, hereditary metabolic disorder. It appears in children [1] and is characterized by a diffuse and generalized metamorphosis of muscle into bone, but with a fatal outcome. 2) Traumatic myositis ossificans circumscripta (traumatic MOC) follows a local acute or chronic trauma, a repetitive trauma or chronic overuse in sports. 3) Myositis ossificans circumscripta without history of trauma (non-traumatic MOC) usually occurs in patients with hemophilia, paraplegia or poliomyelitis, chronic infections, burns or severe head injuries. Non-traumatic MOC can also occur independent of these conditions.

Generally, 75% of all MO cases are associated with trauma. [1],[2] Men and women are equally affected. [3] The lesions can occur at any age, but the highest incidence is reported in the second or third decade of life. Any muscle can be affected, [3] but the most frequent locations are the anterolateral aspect of the thigh and upper arm. Non-traumatic MOC is less frequent and seems to have no preference for gender. [4] Again, adolescents and young adults under the age of 30 years are most often affected. Since non-traumatic MOC is less frequent, no preferential anatomical site can be described.

MO in athletes has been well described. [5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13],[14],[15] This population predominantly suffers from myositis ossificans traumatica, most likely because of contusion or sprain injuries. [5],[6],[7],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13],[14],[15] However, very few reports mention overuse as an etiologic factor. [8],[16]

It is known that a muscle contusion produced by an external force is sufficient to damage the muscle and cause hemorrhage and muscle necrosis. The blood vessels are torn, and thus the blood-borne inflammatory cells gain direct access to the injury site. [12] This causes an inflammatory response. The magnitude of the inflammatory response depends on two main factors, namely, the severity of injury and the degree of vascularization of the tissue at the time of injury. [17] This inflammatory response stimulates fibroblasts and undifferentiated stromal cells to migrate to the connective tissue. The release of multiple enzymes at the place of injury can stimulate the differentiation of fibroblasts into osteoblasts and calcification formation. [7] New bone formation is the result of increased vascularity, metabolism and excess calcium due to hyperemia of the injury. [18] The frequency of occurrence of MO is higher with moderate to more severe types of injuries; however, this does not correlate with the duration of disability. [4] Overuse, on the other hand, has an unknown pathophysiology in the development of MO. It is believed that overuse causes accumulation of anaerobic metabolic waste products and lactic acid, leading to muscle vulnerability. [13],[19] Continuation of the activity can cause micro-trauma and microscopic muscle damage. [13],[19],[20] Its repetitive character, especially in endurance sports, results in diminished perfusion and further muscle damage, thereby initiating an inflammatory reaction. [13],[19] This seems to be enough to encourage the differentiation of the fibroblasts into osteoblasts with the development of MO.

On a review of literature, we could only find two articles in which the development of MO is caused by overuse. The first report was published in 1987 by Gast et al., [8] who described the development of MO in a 16-year-old girl involved in intensive competitive sports, mainly during the 800-m running race. The second report was published in 2007 by Webner et al.[16] who described myositis ossificans traumatica in a 42-year-old recreational runner. He experienced progressive pain during the course of a marathon competition, without notice of a specific event of onset or blunt trauma.

MOC can easily be mistaken for osteomyelitis or a malignant tumor, specifically osteosarcoma or soft-tissue sarcoma. [1],[3],[4],[21],[22] As a rule, there is a rapid onset of pain and palpable swelling which can occur spontaneously or as a result of trauma. [2],[4] Further evolution and progression evolves in two stages. [2],[3],[4] First there is the active phase with pain progression for the first 2-3 weeks, after which maturation of the lesion occurs and pain diminishes slowly. Sometimes a flexion contracture and restricted movement can be observed because of the muscular invasion. Occasionally, there is an elevation of C-reactive protein, white blood cell count and alkaline phosphatase [4],[21] due to muscle inflammation and necrosis resulting from the lesion. Sometimes patients present with minor fever; however, a good general condition is mostly preserved. [4],[21] Generally, there is no palpable adenopathy. [3],[4] Unfortunately, up to 40% of tumor lesions are heralded by a traumatic episode, and therefore history alone is not able to exclude these lesions. [16]

Standard radiographs should be performed at first presentation and are useful for follow-up. Further investigations in the early stage, before maturity of the lesion, include ultrasound and computed tomograms. Ultrasonography [21] can detect these lesions at a very early stage before there are radiological signs. MOC presents as a homogeneous or heterogeneous hypo-echoic mass. Muscle edema is often seen. The earliest radiological findings appear only within 1-3 weeks after the onset of pain. [4],[21] The lesions present as an inhomogeneous soft-tissue mass, with maximum opacity at the periphery and a central radiolucent zone. There is no cortical disturbance, and occasionally, there can be some periosteal reaction. If present, it mostly precedes the opacification of the soft-tissue mass. Computed tomography [3],[21] is the gold standard for diagnosis in the early stages of the lesion. Typical signs are muscle edema and perilesional edema. Calcification of the lesion is characteristic in the periphery. There are no cortical or bone marrow abnormalities. A lucent line separates the mass from the underlying cortex. 99mTc-diphosphonate bone scintigraphy [21] shows increased uptake of tracer in injured muscles, even before radiographic appearance. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful in doubtful cases. [3],[22] The MRI findings are almost always non-specific, but can be present before the appearance of calcifications. MOC appears as a well-defined, inhomogeneous soft-tissue mass. In the early stages, an isointense nodule on T1-weighted images is seen. On T2 images, the periphery of the lesion enhances contrast. MRI findings are more specific in the later stages. A central irregular hypointense zone and diffuse enhancement of the surrounding muscle or soft tissue is seen.

In most cases, spontaneous resorption is the rule, and therefore surgical excision of the lesion is not necessary. [4] It is suggested that smaller lesions and those of the upper extremity are more likely to resorb completely, while large lesions and those occurring near insertion or origin of the muscle are more likely to persist. [10],[23]

Treatment should consist of symptomatic support with anti-inflammatory drugs and relative rest, especially at the early stage of the disease. This is to diminish the pain due to muscle inflammation and surrounding perilesional edema. There is no evidence for the use of indomethacin despite its widespread use in preventing heterotopic ossification after surgery. [19] During the recovery phase, the patient should concentrate on progressive rehabilitation within the limits of pain, prevention of re-injury and regaining full range of motion if limitation occurred. [4] However, a too aggressive protocol can cause muscle strain which will delay recovery. Surgical excision should only be considered in cases of persistent painful masses, repeating inflammation, debilitating function and/or doubtful diagnostics with need for histological investigation. [1],[2],[3],[4],[21] In non-traumatic MOC, surgery can be performed at any time, [2] while the post-traumatic lesions can only be removed safely and completely after maturity to prevent recurrence. [4],[21],[24]

Conclusion Conclusion | |  |

MOC is a rare benign lesion with an excellent prognosis. Spontaneous resolution is seen in almost all cases. Cases in which, despite conservative treatment, a painful mass persists, surgical excision can be considered.

References References | |  |

| 1. | Paterson DC. Myositis ossificans circumscripta, report of four cases without history of injury. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1970;52:296-301.

[PUBMED] [FULLTEXT] |

| 2. | Micheli A, Trapani S, Brizzi I, Campanacci D, Resti M, de Martino M. Myositis ossificanscircumscripta: A paediatric case and review of the literature. EurJ Pediatr 2009;168:523-9.

|

| 3. | Ogilvie-harris DJ, Fornasier VL. Pseudomalignant myositis ossificans: Heterotopic new-bone formation without a history of trauma. J Bone joint Surg Am 1980;62:1274-83.

[PUBMED] [FULLTEXT] |

| 4. | Renault E, Favier T, Laumonier F. Myositeossifiantecirconscrite non traumatique. Arch Pediatr 1995;2:150-5.

[PUBMED] [FULLTEXT] |

| 5. | Beiner JM, Jokl P. Muscle contusion injury and myositis ossificanstraumatica. ClinOrthopRel Res 2002;403(suppl):110-9.

|

| 6. | De Carlo MS, Carrell KR, Misamore GW, Sell KE. Rehabilitation of myositis ossificans in the brachialis muscle. J AthlTrain1992;27:76-9.

|

| 7. | Estwanik JJ, McAlister JA. Contusions and the formation of myositis ossificans. Physician Sportsmed 1990;18:53-7.

|

| 8. | Gast W, Hagena FW, Pforringer W, Remberger K. Multilocular myositis ossificans -damage caused by excessive stress in performance sports? Sportverletz Sportschaden 1987;1:59-63.

|

| 9. | Giombini A, Di Cesare A, Sardella F, Ciatti R. Myositis ossificans as a complication of a muscle tendon junction strain of long head of biceps. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2003;43:75-7.

[PUBMED] |

| 10. | Huss CD, Puhl JJ. Myositis ossificans of the upper arm. Am J Sports Med 1980;8:419-24.

[PUBMED] |

| 11. | Jackson DW, Feagin JA. Quadriceps contusions in young athletes: relation of severity of injury to treatment and prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1973;55:95-105.

[PUBMED] [FULLTEXT] |

| 12. | Jarvinen TA, Jarvinen TL, Kaariainen M, Kalimo H, Jarvinen M. Muscle injuries Biology and treatment. Am J Sports Med2005;33:745-6.

|

| 13. | Miller AE, Davis BA, Beckley OA. Bilateral and recurrent myositis ossificans in an athlete: A case report and review of treatment options.Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87:286-90.

[PUBMED] [FULLTEXT] |

| 14. | Nicholas AA. Myositis of the hip in a professional soccer player, a case report. Am J sports Med1988;16:82-3.

|

| 15. | Smith ET. Myositis ossificans of the humerus (Blocker's disease). Tex State J Med 1960;56:678-80.

[PUBMED] |

| 16. | Webner D, Huffman GR, Sennett BJ. Myositis Ossificans traumatica in a recreational marathon runner. Curr Sports Med Rep 2007;6:351-3.

[PUBMED] |

| 17. | Smith C, Kruger MJ, Smith RM, Myburgh KH. The inflammatory response to skeletal muscle injury: Illuminating complexities.. J Sports Med 2008;38:947-69.

|

| 18. | Chadha M, Agarwal A. Myositis ossificans traumatic of the hand. Can J Surg. 2007;50:21-2.

|

| 19. | Cheung K, Hume P, Maxwell L. Delayed onset muscle soreness: treatment strategies and performance factors. J Sports Med 2003;33:145-64.

|

| 20. | Toumi H, Best TM. The inflammatory response: Friend or enemy for muscle injury? Br J Sports Med 2003;37:284-6.

[PUBMED] [FULLTEXT] |

| 21. | Saussez S, Blaivie C, lemort M, Chantrain G. Non-traumatic myositis ossificans in the paraspinal muscles. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2006;263:331-5.

[PUBMED] [FULLTEXT] |

| 22. | Ehara S, Nakasato T, Tamakawa Y, Yamataka H, Murakami H, Abe M. MRI of myositis ossificans circumscripta. Clin Imaging. 1991;15:130-4.

|

| 23. | Lipscomb A, Thomas E, Johnson R. Treatment of myositis ossificans traumatica in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1976;4:111-20.

|

| 24. | Carmichael SW, Burkart SY, Johnson RD. Myositis ossificans: report of an unusual case. J Othrop Sports Phys Ther 1981;2:184-6.

|

[Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3], [Figure 4], [Figure 5]

| This article has been cited by | | 1 |

Myositis ossificans circumscripta of the psoas muscle due to overuse in an adolescent gymnast |

|

| Julio Javier Masquijo,Federico Sartori | | Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B. 2014; 23(6): 529 | | [Pubmed] | [DOI] | | | 2 |

Non-traumatic myositis ossificans circumscripta: A diagnosis trap |

|

| Ahmed El Bardouni,Monsef Boufettal,Fouad Zouaidia,Mohamed Kharmaz,Mohamed S. Berrada,Najat Mahassini,Moradh El Yaacoubi | | Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2014; | | [Pubmed] | [DOI] | |

|

|

|